France in Africa: Troops withdrawn, financial controls remain

Mali’s Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop called June 16 for the immediate withdrawal of the United Nations mission in Mali (MINUSMA), which numbers just over 15,000 personnel.

“Unfortunately, MINUSMA seems to have become part of the problem by fueling intercommunal tensions,” Diop told the 15-member U.N. Security Council. “This situation is sowing distrust among the Malian population and is also causing a crisis of confidence between the Malian authorities and MINUSMA. The Malian government calls for the immediate withdrawal of MINUSMA.”

After a military coup in May 2021 that enjoyed widespread popular support, France began to withdraw all its troops from Mali — nearly 8,000 at the height of its involvement. By August 2022 they were all withdrawn.

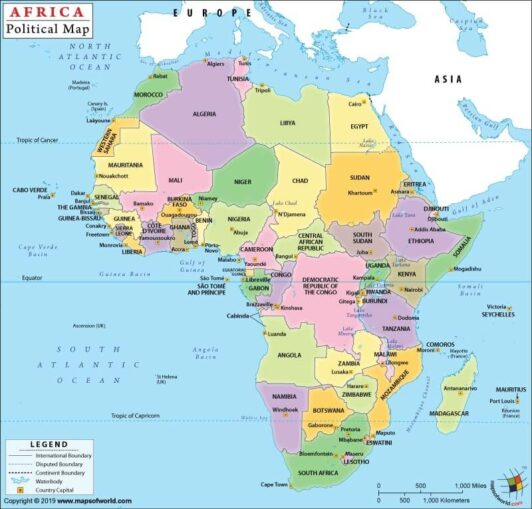

A country of 22 million people and nearly a half-million square miles — twice that of France — Mali is located in West Africa. Mali lies mostly in the Sahel, the transitional zone between the Sahara in the north and the Sudanian savanna in the south, extending across Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea.

The latest developments challenge French imperialist dominance in the region, which Paris still tries to impose through economic machinations.

Historical roots of French neocolonialism

The roots of French imperialist domination of West Africa go back centuries. France’s direct colonial conquest and rule began in the early 19th century. The French ruling class financed this conquest in part with reparations they extorted from Haiti after the victorious Haitian Revolution expelled French rule and ended slavery. However, the debt incurred in paying these reparations devastated Haiti’s economy for over a century.

Starting in the 19th century, the violence, misery and suffering that the French ruling class imposed on Africa, hidden under the pretext of bringing “civilization,” allowed the French rulers to reap massive profits at low cost through forced labor and starvation wages.

As the anti-colonial struggle developed after World War II, Paris saw its empire under siege. In Africa, the great railroad strike of 1947-48 on the line from Dakar, Senegal, to Bamako, Mali, showed how African workers could unite their communities and collectively resist French companies and colonial administrations.

The liberation movements that finally won independence from France in Vietnam and Algeria reinforced the reality that the time of direct colonial rule was ending.

Paris adopted neocolonial policies in West Africa to try to extend its rule. In 1958, a referendum in France’s remaining West African colonies created a French Community. This consisted of France and 14 of its former colonies. The only West African country that said “no” in the referendum was Guinea, which became independent on Oct. 2, 1958.

Guinea was led by Ahmed Sékou Touré, an African labor leader who openly opposed French colonialism and had strong popular support. The French colonial enclave in Guinea responded to the 1958 vote with an intense campaign of sabotage, even removing light bulbs and all typewriters as they left.

In 1960, when Guinea created its own currency, the French state organized another sabotage campaign, flooding the economy with counterfeit money and disrupting everything. This sent a clear message to other countries: Resist French imperialism and it will take revenge.

The former colonies of the French Confederation became “fully” independent in 1960, according to the agreement. In reality, the independence was limited, as Paris agreed to this “independence” after adjusting the structure of the state to allow the leaders it chose to be heads of state. The agreements between these new countries and France gave Paris the right to intervene militarily.

Pretext of combating ‘terrorists’

The French government has used the presence of reactionary groups like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State as a pretext to justify its substantial military presence in countries like Mali, a poor country with profitable gold mines.

There were two military coups in Mali, in 2020 and 2021. The first got rid of a prominent politician, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, who was accused of corruption and mismanaging the fight against al-Qaeda and the IS. The second coup, which had popular support, was directed against a government that the population considered pro-French.

At large demonstrations, supporters of the 2021 coup carried Russian and Chinese flags and homemade signs reading, “France get out!” Mali’s government announced it would hire the Wagner Group — based in Russia — to provide the support and technical training its soldiers needed.

French President Emmanuel Macron’s government announced June 5 that it would reduce its forces in Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire), Dakar (Senegal) and Libreville (Gabon), while maintaining them in Djibouti, a former French colony on the Red Sea. This announcement, following some earlier speeches by Macron, confirmed that France is minimizing its military role in Africa.

Financial controls created by France

In 1945, as part of its colonial policies, France created the CFA franc (tied to the French franc and then the euro), which it later used to guarantee its economic control over the nominally independent countries in the French Community. The CFA franc amounts to repackaged colonialism.

Two groups of countries use the CFA franc as their common currency. One is the West African Economic Monetary Union (WAEMU), consisting of Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo; the other is the the Central African Economic and Monetary Union (CAEMU), consisting of Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

These two groups account for 14% of Africa’s population and 12% of its gross domestic product.

In the current CFA franc system, the African central banks have been obliged for decades to deposit a large proportion of their foreign currency reserves into the French treasury. When the system started, they had to deposit 50%. Currently there is no fixed target.

Macron has changed the CFA franc’s name; it is now the “eco.” French representatives will no longer sit in the bodies of the Central Bank of WAEMU. Although some of the obvious controls are gone, these countries will still have to report to France daily about their central bank transactions.

The new cooperative agreements allow French banking representatives to be brought back. Removing the deposit requirement takes pressure off the French banks to offer a fair interest rate on the deposits. French control is less obvious but still exists.

According to Ndongo Samba Sylla, a Senegalese development economist at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s West Africa Office in Dakar, Senegal, “France is facing more and more pressure in Africa, militarily speaking, because people oppose its interventions, and as we see in Sénégal, economically speaking as well.”

Source: “Africa’s Last Colonial Currency: The CFA Franc Story,” Fanny Pigeaud and Ndongo Samba Sylla, Pluto Press.