Book review: a political pilgrimage during six decades

“My Whirlwind Lives — A Political Memoir and Manifesto,” by Dee Knight, Guernica World Editions, Toronto, 2022.

Class-struggle activist Dee Knight’s new book lives up to its promise of telling through a memoir a political history of the last six decades and presenting a program worthy of discussion for staying in motion through today’s storms.

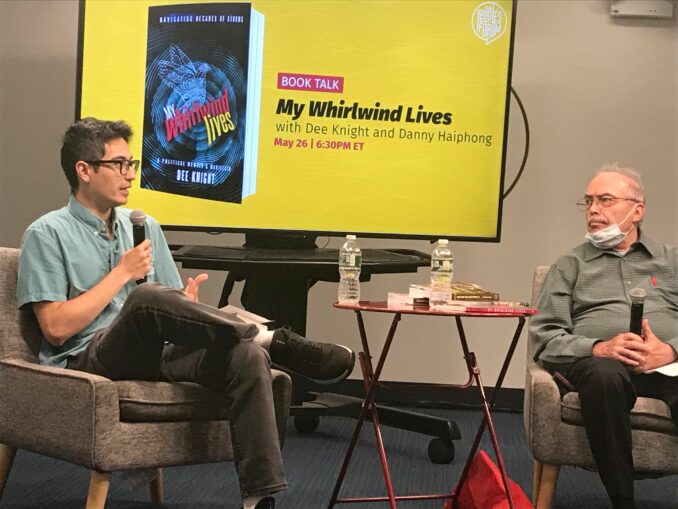

Danny Haiphong (left) interviews Dee Knight at book launch at People’s Forum in New York City, May 26. Credit: John Catalinotto

To launch his book May 26, Knight chose an excellent venue, the People’s Forum in New York, where political journalist Danny Haiphong, author of “American Exceptionalism and American Innocence,” interviewed the veteran activist.

Knight hopes that young people newly interested in socialism will be looking for the honest and vivid recounting of the struggles, victories and setbacks provided by his memoir to inform their approach to today’s challenges. Others share that hope, as an evaluation of these past experiences of people sharing similar goals can help undo the misinformation and misevaluation of “the ’60s” offered by analysts who serve the ruling class.

What first surprises the reader is that Knight’s early political hero was Barry Goldwater. The young seeker of political truth quickly leaves the reactionary Arizona senator behind, his journey accelerated by the pressure of U.S. imperialism’s attempt to crush the national liberation movement in Vietnam.

The threat of military inscription presents an entire generation of young people with a sudden moment of truth. Faced with this life-and-death choice, they quickly question authority. Knight seeks answers, decides that the war is criminal and that he won’t go.

Knight’s trek toward becoming a socialist fighter in the center of the empire exposes him to new heroes, followed by new disappointments: the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy in 1968. The Eugene McCarthy campaign that promised peace but delivered nothing. He develops a growing disgust with both big imperialist political parties.

Those who know the war is an imperialist crime have three obvious ways to resist: refuse the draft and go to prison; enter the military and organize against the war — or that failing, desert; or go into exile. Knight chooses the last and winds up in Canada. There he both participates in the local class struggle, organizing in labor unions, and he helps found the Amex newsletter that focuses and mobilizes the U.S. emigrés.

Using Knight’s words, these emigrés include “expatriates,” who are trying to survive and integrate into Canadian society, and “exiles,” who are trying to survive as they organize a struggle to return to the United States with the benefit of a well-deserved amnesty.

His memoir describes that struggle for amnesty, his role in it and that of many of the friends and comrades he made in the course of years leading up to what he describes as a partial victory during the Jimmy Carter administration. The war criminals inhabiting the U.S. state apparatus concede that those avoiding the draft can return without punishment but deny this to those who deserted from the military. Knight points out the racist character of that particular discrimination.

Knight seeks action. Worn down by an endless colonial war, the Portuguese army in April 1974 revolts and overthrows a decades-long fascist regime, opening the door to a possible workers’ revolution. In 1975 Knight goes to Lisbon to witness the Carnation Revolution firsthand.

By then he is a committed anti-imperialist, one who wants a socialist revolution, also in the United States. Knight credits this development mainly to his experience during the Vietnam War, living as an exile and organizing the battle for amnesty.

He joins Workers World Party at that time, but the whirlwind picks him up again in the mid-1980s and blows him to Managua, Nicaragua, for three years to help the Sandinistas develop computerized newspaper publications. The Ronald Reagan gang has backed reactionary “contras” to attack the revolution, and Knight is fighting back.

He says his memoir is also a “manifesto,” where he lays out today’s opportunities for pro-socialist action. Knight explains that he has joined the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) to work on specific struggles in a movement that breaks out of the isolation that revolutionary communist parties endure in the United States.

And he makes good arguments for supporting specific struggles like the “Green New Deal” that have been raised and made popular by DSA adherents and other progressives who are in Congress. Knight names progressives who at present are in Congress allied with the Democratic Party, like Senator Bernie Sanders, the members of “the Squad,” and especially Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as promoting the struggle.

The whirlwind never stops. Having found out that all these representatives voted for the military budget that passed Congress, including the additional money for promoting the proxy war against Russia now being fought in Ukraine, Knight made an addendum to the second edition of “My Whirlwind Lives” to comment on that vote.

It reads: “This meant endorsing the official narrative blaming Russia for opposing neo-Nazis in Ukraine and fighting against NATO expansion to its border.”

When you read Knight’s book, avoid shelters and go with the flow.

Catalinotto is the author of Turn the Guns Around, which covers the struggles of those who fought against the Vietnam War from within the military.