Heroes of the 1937 Flint Sit-down Strike

February 11 marked the 85th anniversary of the victory in the Flint Sit-Down Strike. While this is one of the most famous battles in U.S. labor history, too little is said about the Black workers who helped bring about this victory.

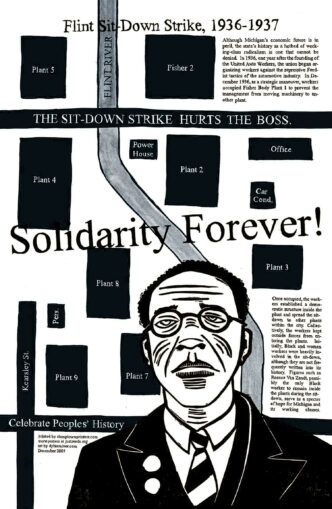

This graphic pays tribute to Black sit-down striker Roscoe Van Zandt. Graphic: Dylan A.T. Miner

Trying to organize a union at General Motors was dangerous. GM was the force behind a union-busting KKK offshoot in Michigan known as the Black Legion — black being the color of their hooded robes. Black United Auto Workers supporters had to meet in secret by candlelight, in church basements and private homes.

According to J.D. Dotson, a Black Flint GM worker and member of the Communist Party USA, “In 1929 we started to organize in secret — five Blacks and two whites. We would go from place to place in open cars in zero weather to get a union started. We hid in basements. We couldn’t let nobody know what was going on, or they would go back in the shop and tell the boss.”

Dotson was interviewed in 1982 by Frank Hammer, former president of UAW Local 909 at the now-closed GM Powertrain plant. Dotson described the particularly oppressive conditions faced by Black GM workers: “You didn’t know from day to day whether you were going to work. When we did, we worked from six in the morning to six or seven in the evening.

“You didn’t get water. They had one man who would come around with one of them old pint milk bottles, rinse it out and give you water. We could drink water with one hand, watch for the boss and keep working with the other hand. You had to eat right on the job with dust, oil and everything in the foundry. You didn’t wash your hands, because if you did, you didn’t have a job. This was not one day — this was every day.”

During the occupation of GM in Flint, which began Dec. 30, 1936, and lasted 44 days, Dotson carried messages from inside and outside the occupied plants and between picket lines. (The full interview, originally printed in the rank-and-file caucus newsletter Straight Talk, can be read at facebook.com/straighttalkuaw909.)

GMs Jim Crow

At that time GM was a Jim Crow operation, only hiring African Americans for janitor jobs or the dirtiest, hardest foundry jobs. During the sit-down strike, Roscoe Van Zandt stayed inside his plant from beginning to end. At first he kept to himself, but Socialist Party members like Kermit Johnson and Howard Foster educated white workers on the need for solidarity. There was one bed in the plant and the sit-down strikers gave it to Van Zandt — he was older than most of them.

When the strikers emerged from Chevrolet Plant Number Four victorious, they were led by Van Zandt.

Henry Clark was a lead union organizer in the Buick foundry plant, idled during the sit-down. Some of the clandestine meetings had been held in his and other African American workers’ homes; others were at Canaan Baptist Church. Clark and other Black workers “stayed in the background, but we supported [the sit-downers] 100% . . . we were right behind them and helped in any way we could.” (University of Michigan, Flint Campus, Labor History Archives, Oral History, Henry Clark)

Black workers are critical to class struggle

Clark and another Black Buick worker, Ellsworth Steen, were elected shop stewards after the strike victory. Flint is one example of many that illustrate the pivotal role played by the most oppressed workers throughout labor history.

Black workers today still face especially dangerous working conditions, evidenced by the attempted murder of a Black FedEx delivery driver, 24-year-old D’Monterrio Gibson, while on his job in Mississippi. FedEx is a totally nonunion company.

The pay and benefit differential between unionized and nonunionized workers is greatest for Black and other workers of color. “Unionized Black workers are paid 13.7% more than their nonunionized peers,” according to a 2020 Economic Policy Institute report. But like the Black heroes of 1937, they have to contend with vicious union busting, like that directed at the Black-majority Amazon workforce in Bessemer, Alabama, or the fired Starbucks workers in Memphis, Tennessee.

The most important lesson from labor history is that solidarity wins.