Panama’s 1964 popular anti-imperialist explosion

Beluche is a Panamanian political analyst. Translation: John Catalinotto.

On January 9, 1964, a true popular revolution in the full sense of the word caused a turning point in U.S. policy in Panama, when 60 years of accumulated contradictions exploded. The mass action shattered the dream of riches that the Panamanian oligarchy had painted in 1903 to impose what they called an “independent” state.

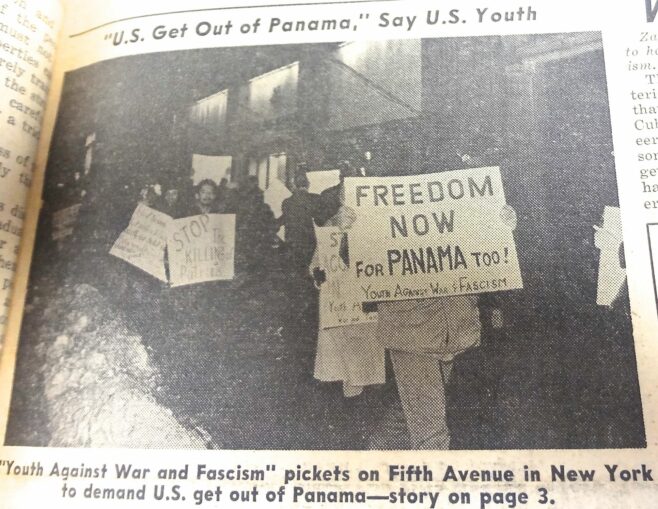

Above graphic shows photo from Jan. 22, 1964 issue of Workers World: Youth Against War and Fascism in solidarity with Panamanian struggle. New York, Jan. 14, 1964.

In reality, Panama was a “protectorate,” that is, a U.S. colony, and then the disgraceful Hay Bunau Varilla Treaty [of November 1903, that] handed over the canal to the U.S., “as if they [the U.S.] were sovereign.”

It should be remembered that the grandparents of our oligarchy, since 1903 felt comfortable with the colonial situation, believing themselves to be Yankees at heart. The popular sectors, on the other hand, found it difficult to find clarity in the construction of their own political project. Nevertheless, from the beginning the masses devoted themselves to the defense of sovereignty, because they understood that the prosperity of the country and their own prosperity depended on it.

In 1964, the accumulated experience of the Panamanian people emerged, led by its most combative sectors, which had confronted the imperialist colonial presence in the 1925 Tenant Strike, in the Anti-Bases Movement of 1947, as well as the great deeds of the student movement of the 1950s, Operation Sovereignty and the Sowing of Flags. This took place in an environment fermented by the influence of the 1959 Cuban Revolution.

On January 9 that year, upon learning of the aggression suffered by the students of the National Institute, of the Panamanian flag sullied by the “Zonians” [U.S. citizens living in the Canal Zone] and of the brutal repression of the Yankee soldiers, the Panamanian people burst with indignation and came out en masse, spontaneously, to cross the fence and plant a flag.

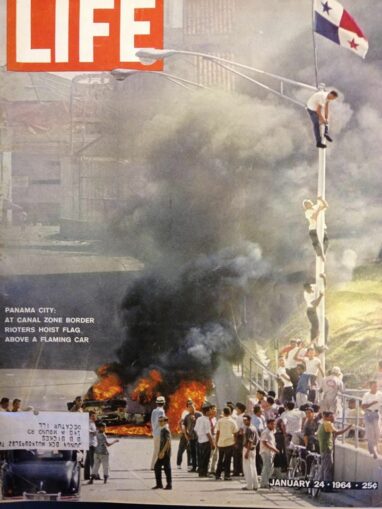

Panamanians fight to win sovereignty over Canal Zone, January 1964.

Panamanians faced tanks

There, at the barricade or simply lying on the ground around what today is the “Legislative Palace,” thousands bravely faced the shrapnel of the tanks, led by popular leaders of the leftist organizations, from some youth wings of the People’s Party (Communist) with Adolfo Ahumada or Victor Avila and others, those of the Vanguard of National Action (VAN) of Jorge Turner and the hosts of what would later become the Revolutionary Unity Movement (MUR) of Floyd Britton.

A “people” that socially was a “young, vigorous and rapidly expanding proletariat” (an expression of the industrialism of the ’50s and ’60s) was organized in the Committees for the Defense of Sovereignty (Comités de Defensa de la Soberanía). These committees were embryos of dual power that filled the power vacuum in the absence of the oligarchic government-state which was erased from the streets.

These popular committees organized everything from the procurement of weapons, to the defense and attack, and the civil organization, which was expressed in blood donations and transportation of the wounded to hospitals. In this regard, it is advisable to read: “Significado y consecuencias del 9 de Enero,” (“Significance and Consequences of January 9”), José Eugenio Stoute, Revista Mujeres Adelante No. 13, January, February and March 1989.

An enormous column of people — of up to 60,000 people, according to Stoute, surrounded the Presidency of the Republic, demanding arms to confront the imperialist aggression.

The oligarchic government of Roberto Chiari, son of former President Rodolfo Chiari, who in 1925 asked for U.S. military intervention to crush the Tenant Strike, decided on two opposing measures: one, the National Guard was placed in barracks, so that its weapons would not be used by the people in defense of national sovereignty; two, trying to appease the popular fury, Chiari broke diplomatic relations with Washington.

That Chiari took this desperate measure did not reflect any nationalist desire of the oligarchy but rather the fear the government felt before the insurrection that threatened to force its way into the Palace of the Herons.

The insurgent people resisted for three days in the streets of the cities of Panama and Colon. During those three days, the people did not limit actions to planting flags, but to confront, with the few weapons available, the imperialist troops. There were several deaths that the “governor” of the Canal Zone recognized.

In the three days, every symbol or property of U.S. companies was looted and burned, from the famous Panamerican Airlines building to the Chase Manhattan Bank branches. Dozens of automobiles with Zone license plates were overturned and burned along the streets of the city.

Panama’s government, which had cowardly gone into hiding, began to take the National Guard out of the barracks on Jan. 11 and 12. However, it made these moves not to defend the attacked nation but to arrest the popular leaders of the insurrection, a great number of whom ended up in the Modelo prison.

Gesta wins sovereignty

The repressive work of the liberal governments of Chiari and Robles would continue in the following years, targeting the student leader Juan Navas, who had been wounded during the Heroic Deed (Gesta) of January and had traveled to the Soviet Union for medical treatment. Upon his return from the USSR, in 1966 he was arrested by the regime’s political police, tortured, murdered, and his corpse was thrown in the Colon Corridor. This was followed by a trial to incriminate his comrades of the People’s Party of that city.

The sacrifice of the martyrs and the popular insurrection of 1964 were not in vain, but on the contrary a victory that took shape over time and that today is felt all over the country. The criterion was imposed, which before 1964 was sustained only by popular sectors of the left, that it was necessary to end the colonial statute of 1903, repeal the Hay-Bunau Varilla and negotiate a new treaty on the Panama Canal, which would eliminate the “Zone,” the military bases and transfer the administration of the waterway in a peremptory term.

The 1977 Torrijos-Carter Treaty reflected these demands, despite its amendments and the Neutrality Pact [that gave the U.S. the right to defend the Canal].

The economic prosperity that today prevails over the country is undoubtedly due to the January 9 Gesta, because it is based on the income that the Canal is producing, which Panama did not receive earlier. Because, contrary to what the Panamanian oligarchy maintained — an oligarchy that, until 1999, feared the withdrawal of U.S. military bases — it has been demonstrated that “sovereignty does pay off.”

Unfortunately, a social class that has been called the new “Zonians” has appropriated most of the prosperity the canal produced. This class is none other than the descendants of the same oligarchy that sold the country in 1903, that for a hundred years acted as an internal ally of North American colonialism and that accused the popular leaders of ‘64 of being “communists” and the Martyrs of being “looters and thieves.”

This appropriation of the canal’s benefits, which is the opposite of what Omar Torrijos maintained when he stated that it should be given the “most collective use possible,” is due to another event: the Dec. 20, 1989, U.S. invasion of Panama [under the administration of U.S. President George Bush Sr.].

Translator’s note: Workers World Party and its youth organization, Youth Against War and Fascism (YAWF), trained its new recruits in proletarian internationalism. Thus, in January 1964, I was assigned to write a leaflet for and organize a demonstration in solidarity with the youth of Panama who had confronted the Zonians and U.S. imperialism in Panama. It read in part, “The youth in the U.S. must make clear its resistance to all forms of police brutality and U.S. Army terror, whether it is practiced against Puerto Ricans and [African Americans] at home, or against Vietnamese and Panamanians abroad.”

Determined YAWF members held a symbolic demonstration in front of the U.S. Army, Navy and Marine Information Center at 5th Avenue and 53rd Street in Manhattan, New York, on Jan. 14, 1964, in subfreezing temperatures and snow, in a challenging political climate following the recent Nov. 22, 1963, assassination of President John F. Kennedy.