Sidney Poitier: A brilliant ‘force of nature’ on and off the screen

After the heartbreaking news of Sidney Poitier’s death at 94 on Jan. 6, unparalleled adjectives have been used — from the most famous to ordinary film lovers — to describe his towering legacy and talent as trailblazing, regal, inspiring, noble and more. His career as an actor and director spanned 70 years.

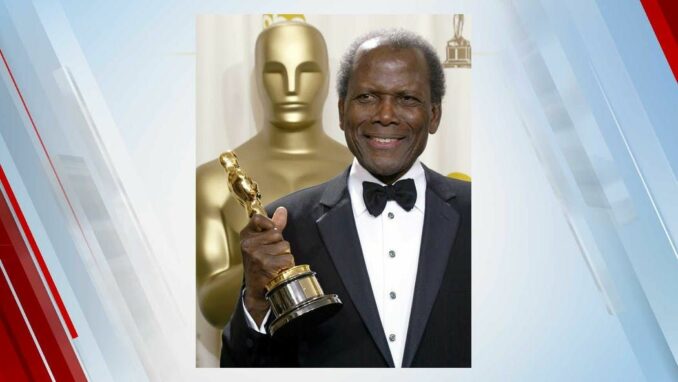

Sidney Poitier received an honorary Oscar in 2002.

Poitier was presented an honorary Academy Award in 2002 “for his extraordinary performances and unique presence on the screen and for representing the motion picture industry with dignity, style and intelligence throughout the world.”

Black actors like Oscar winners Denzel Washington, Halle Berry, Morgan Freeman and Louis Gossett Jr. and lesser known actors have said they might not have become the actors they are today if not for Sidney Poitier paving the way.

Poitier once stated, “I made films when the only other Black on the lot was the shoeshine boy — as was the case at Metro [Goldwyn Mayer]. I was the lone guy in town.” (hollywoodreporter.com, Jan. 7)

When Black director Spike Lee paid homage to Sidney Poiter on CNN commentator Don Lemon’s Jan. 7 show, he described the actor’s impact on U.S. society as comparable to Jackie Robinson and Joe Louis.

What were the parallels between this actor and these two athletes? Jackie Robinson, who played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, was the first Black player to break the color barrier in the then all-white Major League Baseball in 1947 and was seen as a precursor to the Civil Rights Movement.

Joe Louis, aka the “Brown Bomber,” while not the first Black heavyweight champion — that was Jack Johnson from 1908-1915, gained worldwide popularity, especially in the Black community, when he regained his heavyweight crown in 1938 after knocking out a German boxer, Max Schmeling, who symbolized the rise of Nazism before World War II.

So while Poitier was not historically the first African American actor, female or male, in Hollywood, he was the first major Black actor to consistently play characters that were not racially insensitive or stereotypical. These were the only roles offered by predominantly white studios before Poitier’s major breakout role in the 1950 film, “No Way Out,” where he played a doctor terrorized by a white racist, played by Richard Widmark. Even the great Paul Robeson was forced to play some stereotypical movie roles during the 1930s.

When Poitier was accused by some Black actors of playing sanitized characters like doctors, teachers and other professionals which were acceptable to the tastes of white audiences, he replied he felt it was important to remain true to himself and to bring dignity to any character he decided to play, being conscious of the racist degradations facing Black people, including actors, in previous eras.

In a 1967 New York Times interview, Poitier said of his acceptance of certain roles: “It’s a choice, a clear choice. If the fabric of the society were different, I would scream to high heaven to play villains and to deal with different images of Negro life that would be more dimensional. But I’ll be damned if I do that at this stage of the game.” (Washington Post, Jan. 7) In fact, in his autobiography, Malcolm X praised Poitier for his positive screen image.

Career parallel with Civil Rights struggle

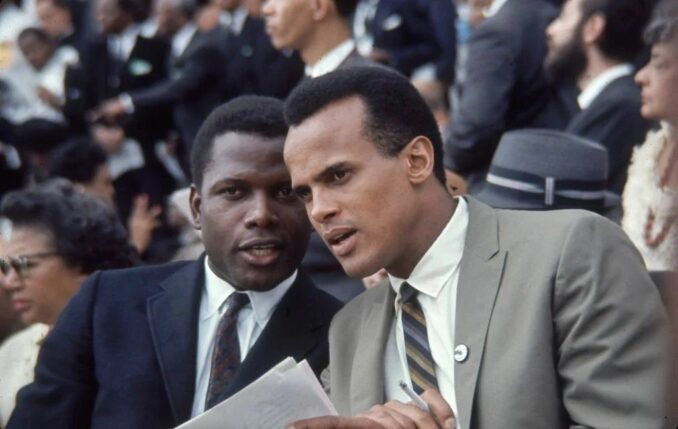

Sidney Poitier and Harry Belafonte attend the 1963 March on Washington.

Sidney Poitier was lucky to be alive, since he was born three months prematurely to tomato-farming Bahamian parents while they were visiting Miami. He was raised on Cat Island in the Bahamas, but he returned to Miami as a teenager. He then traveled to New York City, hoping to become an actor.

At the time, in the mid-1940s, he could barely read a script until a Jewish worker assisted him with reading from a newspaper every night while Poitier worked as a dishwasher. He joined the American Negro Theater after leaving the Army in 1947. There he met young legendary actors and future activists, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis and lifelong friend, Harry Belafonte.

During the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, Poitier became the first Black actor nominated for a best actor Oscar in 1959 for the 1958 film, “The Defiant Ones.”

He starred on Broadway in Black playwright Lorraine Hansberry’s award-winning play, “A Raisin in the Sun,” in 1961 and reprised his Tony-nominated role in the movie made of the play. Both take place in Chicago, with a Black family contemplating the consequences of moving to an all-white suburban neighborhood.

Even before the signing of the historic Civil Rights Act, Poitier became the first Black actor to win the best actor Oscar in 1964 for the 1963 film, “Lilies of the Field.”

Off-screen, Poitier along with Belafonte and other actors, Black, white and Latinx, were active in the Civil Rights struggle, whether marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Washington, D.C., Alabama and elsewhere or raising funds for the movement. Poitier participated in Resurrection City in Washington, D.C., in the summer of 1968 following the assassination of Dr. King.

‘They call me Mister Tibbs’

In 1967, he became a number one box office draw with three hit films: “To Sir With Love,” “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” and “In the Heat of the Night.”

While filming the latter movie, Poitier faced racism in Tennessee as recounted by the film’s director, Norman Jewison. Poitier did not want to film in Mississippi, the setting of the film, due to the racism he and Belafonte had faced in the Deep South when encouraging Black people to register to vote. Poitier was forced to stay in a segregated hotel for four days of the film’s shooting. He slept with a gun under his pillow for protection following racist threats.

The most powerful scene in “In the Heat of the Night” is when Poitier’s character, Virgil Tibbs, a Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, police officer, is slapped by a racist plantation owner, played by Larry Gates. Without hesitation, Tibbs slaps him back, while giving him a defiant stare. This reaction symbolized the period of heroic struggle for social equality in the Deep South and rebellion in the Northern cities against poverty and police brutality. Poitier demanded that what has become known as “the slap heard around the world” remain in the script, or he would not do the scene at all.

Jewison said about the scene, “As the film echoed the power of that moment around the world, I think Sidney represented the conflict between people in America.” (Hollywood Reporter)

In reaction to actor Rod Steiger’s character, a racist sheriff, calling Poitier’s character a racist slur, Poitier replies forcefully, “They call me Mister Tibbs.”

Poitier also portrayed the first Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and the South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela in TV movies.

‘His brilliance shone through’

Sidney Poitier has been described, and rightfully so, as a once-in-a-lifetime, singular talent. His brilliance shone through in spite of racism.

That the roles offered to him were limited still rings true for Black actors today in Hollywood. As the Black New York Times critic Wesley Morris — who deemed Poitier the “greatest American movie star” — stated in his Jan. 7 appraisal: “Mr. Poitier achieved his greatness partially as a matter of ‘despite.’ He achieved all he did despite knowing what he couldn’t do.

“I mean, he could’ve done it — could’ve played Cool Hand Luke, could’ve been the Graduate, could’ve done ‘Bullitt,’ could have been Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. There are maybe a dozen roles, capstones, that nobody would have offered to Mr. Poitier because he Wouldn’t Have Been Right for the Part.” (New York Times)

The Oscar-winning actor Lee Grant, a co-star in “In the Heat of the Night,” described Poitier on her Twitter feed as a “force of nature” and “one of most intelligent, beautiful and unstoppable human beings I’ve ever known. He made our world, and my life, better in ways we still may not entirely comprehend. Calling him a legend doesn’t do it justice. He was Sidney Poitier.”