Massive protests in Niger, Burkina Faso demand French military get out

Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger are former French colonies, where the struggle against France’s presence in the Sahel region of Africa has been most intense, with mass actions marking the last two weeks of November. Resistance in these countries takes many shapes and forms.

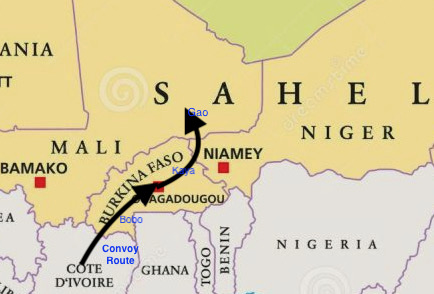

Black line shows route taken by French Army convoy — which sparked protests throughout Burkina Faso.

In a series of meetings earlier this year, Washington agreed to offer strong military and financial support to French imperialism in Africa. After French President Emmanuel Macron announced a reduction of French forces in Mali to 2,000-3,000 troops, the first such meeting was held in July at the Pentagon.

At that meeting, French Defense Minister Florence Parly signed an agreement with Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin that their special forces would cooperate, especially in the Sahel. A telephone meeting on Oct. 21 confirmed their “collaboration on counterterrorism in the Sahel.”

The Sahel is the zone stretching across the whole African continent, between the arid Sahara desert to the north and the mixed woodland-grassland humid savannas to the south. Most of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger are in the semi-arid Sahel region.

Reactionary religious-based groups, like al-Qaida and the Islamic State (ISIS), operate in all three countries, as do remnants of local separatist movements. These groups engage in armed attacks on French (and U.S.) special forces, as well as on each other and civilian communities.

In contrast, mass popular organizations held big, militant protests and strikes and offered political support to factions in their armies that oppose French imperialism.

The convoy from hell

The problems the French army had in moving a convoy from the Ivory Coast (Côte d’Ivoire) to Gao in Mali revealed the variety of forms the anti-imperialist struggle takes.

The French had planned to make Gao its main military base in Mali. Gao is the last river port on the Niger River in Mali, before it flows into Niger. A French base in Gao would give French imperialism a commanding military position in northern Mali up to the Algerian border, including the cities of Timbuktu and Tessalit, the more populated areas of Niger to the south and the area where Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger meet, which is where the ISIS-like groups operate.

Gao is isolated, without a major airport and off any road grid. The military base needs to be built with heavy equipment and supplies. French newspapers (Libération, Nov. 20, for example) have been filled with pictures and stories of French troops consolidating their position in Gao. To fortify its position, the French Army sent a convoy from the Ivory Coast, which has a sea port.

Heavy loads would normally get stuck in the roads of the Sahel. The French convoy consisted of over 60 heavy-duty trucks capable of going through sand with a heavy load.

The route chosen was north through the Ivory Coast, then through Burkina Faso to Niger. After Niger, the convoy would cross into Mali and head north to Gao.

In the city of Bobo Dioulasso, the second largest city in Burkina Faso, university students held a demonstration at the last minute calling for the end of French bases in Burkina Faso. (burkina24.com, Nov. 16)

Every Burkina Faso community it entered met the convoy with protests blocking the roads. At Kaya, a large town northeast of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, a crowd blocked the convoy and forced it to shelter in a fenced-off truck lot. According to reports spread widely on social media, during the rally 13-year-old Aliou Sawadogo noticed a small French drone flying over the crowd Nov. 24 and brought it down with his slingshot. Sawadogo was proclaimed No. 1 Burkinabe sniper.

When the convoy passed from Burkina Faso to Niger Nov. 27, there were two big demonstrations, one in western Niger at Téra and the other in Ouagadougou. The one at Téra attracted many young students, according to the videos on France’s TV5, as well as adults, who erected barricades of burning tires and logs, tried to seize some trucks and kept the convoy from proceeding for five hours.

The demonstration in Ouagadougou raised the suspicion common among Burkinabes that this convoy is bringing weapons to supply the ISIS-type groups that threaten the state’s stability. The French military has denied this charge.

This all takes place while the trial of the assassins of former Burkina Faso president and liberation leader, Thomas Sankara, who was targeted by French and U.S. imperialism, is under way.