A Marxist history of HIV/AIDS − Part 5: Mobilization wins against AIDS in New York City, 1981 − 1986

HIV refers to human immunodeficiency virus. If left untreated, HIV can lead to the disease AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome). HIV is transmitted by four fluids: semen, vaginal fluid, blood and breastmilk, and through mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy/birth.

A chapter of People with AIDS (PWA), the group started in 1982 by gay activist Bobbi Campbell in San Francisco, was established in New York City that year by Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz.

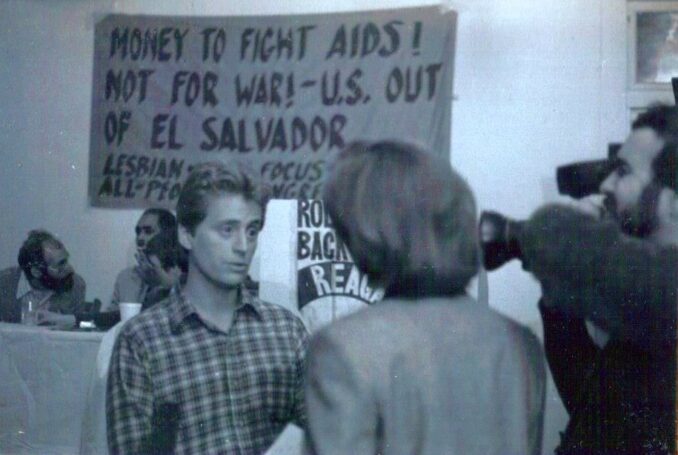

After speaking on the HIV/AIDS crisis, Workers World Party comrade Leslie Feinberg (facing) talks to attendees at a 1983 Boston meeting of the Lesbian and Gay Focus of the All Peoples’ Congress. Credit: WW Photo: Rachel Nasca

Most significantly for the East Coast, on Jan. 12, 1982, in Larry Kramer’s apartment in New York City, a group of gay men founded the Gay Men’s Health Crisis — later known as the Gay Men’s Health Center (GMHC). Paul Popham, a Wall Street banker, was elected president of the organization. Popham’s conservative views on fighting HIV/AIDS often clashed with Kramer’s radical views. Later this would cause Kramer’s ouster from GMHC and his refusal for over 30 years to work with the organization.

On March 14, 1982, Dr. Jim Curran, an epidemiologist, became one of the first U.S. medical professionals to speak out on the infectious nature of HIV. He spoke to a crowd of hundreds of doctors — many who were gay and lesbian — at the first-ever meeting of New York Physicians for Human Rights. Curran predicted that the physicians would spend the rest of their working lives fighting this mysterious illness. Despite growing concern, and despite the presence of LGBTQ+ physicians at the event, his words were hardly heeded, though ultimately turning out to be true.

GMHC quickly set up an AIDS Hotline for crisis counseling. It was started by GMHC member Rodger McFarlane using his own home phone. This was perhaps the first hotline of its kind, most certainly the first in New York City, and served to help spread information about the virus in its early days to thousands of New Yorkers, before much of anything was known.

This single phone line did more for raising awareness than any government entity at that point. In fact, the Reagan administration had still not uttered a single word on the epidemic!

Almost a year after Dr. Curran’s watershed speech, the virus was still not being taken seriously. Larry Kramer published his own historic speech on AIDS in a March 27, 1983, editorial in the New York Native, “1,112 and Counting.” Kramer lambasted the gay community for apathy towards this mysterious illness that was killing its members. He wrote: “In all the history of homosexuality, we have never been so close to death and extinction before. Many of us are dying or are dead already.” (bit.ly/3AAEdVi)

Kramer went on to correctly state that if the illness were affecting majority white, heterosexual, middle-class men and women, millions of dollars would have been poured into research. He cited the 1982 Tylenol scare in which $10 million was provided by the U.S. government to research deaths ultimately shown to result from drug tampering.

From 1981 to 1987 at the beginning of the epidemic, 60% of AIDS cases were among white people in the U.S. (tinyurl.com/2mzmvyx8) But because the illness affected mostly gay and bisexual men, people who injected drugs and eventually Black and Brown people, HIV/AIDS was not given the same attention and care as other less serious health crises.

Kramer criticized the lack of response from the city of New York, where Mayor Ed Koch skirted the issue of AIDS for the first two years it ravaged the city. Kramer also criticized bourgeois media such as the New York Times for their scant coverage.

To drive Kramer’s points home, the New York Native then called for 3,000 volunteers to disrupt the city’s traffic and engage in act after act of civil disobedience to force New York to pay attention to the epidemic that was hitting its inhabitants.

The city management of New York, terrified at the idea of 3,000 people in acts of civil disobedience, quickly formed the Office of Gay and Lesbian Health Concerns to address the epidemic. Despite this development, the Koch administration continued to drag its heels on making any major shifts in fighting HIV/AIDS in the city until 1985.

However, in 1984 more street activism and mobilization began to occur in New York City, not just against the mayor’s apathy, but in protest of the entire U.S. government’s refusal to deal with the epidemic.

In a July interview with this writer, Workers World Party San Antonio member Shelley Ettinger, who lived in New York City during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, commented on the intense street mobilizations that began in 1984. She recalled one large protest that year at New York City’s federal building against then President Ronald Reagan and his administration.

These protests occurred during the 1984 presidential election, in which Reagan easily defeated Democratic Party nominee Walter Mondale. In a series of events that surprised absolutely no one who understood the bankrupt, anti-democracy machine that is the two-party system, neither the Republican Party nor the Democratic Party mentioned the AIDS epidemic in their press releases, campaigns or debates. When Reagan spoke at his victory celebration on election night, he said “The best days of America lie ahead.”

By this time in the U.S., over 7,000 known people had AIDS, and there had been over 5,500 deaths. (bit.ly/3xaaL6l)

In 1986, Gay Men of African Descent was founded in New York City and began to combat the AIDS epidemic in the Black gay male community. Even within the growing queer HIV/AIDS fightback movement, the crisis of AIDS within the Black community was largely being ignored due to anti-Black, racist attitudes within the white gay community. This would continue with gay Black men, Black women and especially Black trans women being disregarded in the struggle for HIV/AIDS treatment and fightback — a critical and catastrophic error that had consequences lasting into today.

The masses force Reagan’s hand

In 1985, four years after the New York Times had published its throwaway article on a “rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals,” and after thousands of people were suffering from AIDS with thousands dead — after years of LGBTQ+ people, people of color, people who inject drugs and poor people being blamed for the plague and after years of discrimination in housing and employment, xenophobia, racism, anti-Blackness and the phony “War on Drugs” — President Reagan finally spoke on HIV/AIDS. After demonstration on demonstration, after networks of solidarity held rallies, direct actions, vigils and civil disobedience, Reagan was finally forced to confront the epidemic he had not only intentionally ignored, but had mocked in private.

His first mention of AIDS was only to express his hesitance in allowing children with AIDS to attend public school. In fact, Reagan went so far as to bar his surgeon general, Dr. C. Everett Koop, from speaking publicly on the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

When Reagan finally relented in 1986, after more public pressure, he pressured Dr. Koop to keep any information released “in line with conservative policies.” In other words, Reagan advocated continuing to ignore the oppressed communities affected by HIV/AIDS, providing as little funding as possible against the epidemic and drowning out the voices of millions of people demanding he take action.

Dr. Koop, however, took matters into his own hands and released information that actually called for comprehensive AIDS education and rejected mandatory testing. During the epidemic, this was the first instance of someone directly allied with the U.S. ruling class turning against its reactionary denial of the crisis and actually making a correct step.

Despite Reagan’s complete mishandling of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, which fueled all sorts of further discrimination against nationally oppressed groups, LGBTQ+ persons, people with disabilities and working-class people, the early years of activism — at first mostly vigils and pleas for help — were soon transformed into militant actions led by militant groups that called for complete disruption of “business as usual” policies of the capitalist-imperialist U.S.

These militant actions would go on to dominate the struggle against the HIV/AIDS epidemic during the late 1980s and early 1990s, as contradictions sharpened, conditions worsened, and anti-capitalist militancy grew.

Ellen Catalinotto, who contributed to this article, worked for 22 years as a midwife in New York City hospitals, where she participated in research that led to the first breakthrough in preventing mother-to-child transmission of the AIDS virus. Devin Cole is a transgender Marxist organizer and writer. They are the president of Strive (Socialist Trans Initiative), a transgender advocacy organization in northwest Florida, and a member of the Workers World Party – Central Gulf Coast (Alabama, Florida, and Mississippi) branch.