From chattel slavery to modern prisons

The following remarks were given during the 50 Years of Resistance: Black August & Attica live broadcast hosted by the Prisoners Solidarity Committee of Workers World Party Sept. 2. Crissman is a co-editor of Tear Down the Walls.

I am always very struck when imprisoned people compare their situations to that of an enslaved person. That is an accurate portrayal of how prisons, jails and detention centers have historically functioned and continue to function in our capitalist-run society.

I live and organize in Texas and am a perpetual student of how cages have been institutionalized in this part of the world. Prior to the introduction of chattel slavery in what is now called Texas, Spanish colonizers implemented encomiendas. An encomienda was a grant by the Spanish crown to colonists in the Americas conferring the right to demand tribute and forced labor from the Indigenous inhabitants of that land.

Around the beginning of the reign of Spanish colonizers in the Western hemisphere, African peoples were violently ripped from their continent and subsequently branded as property, in order for a few people to accumulate vast fortunes from the spoils of their stolen labor. The beyond-brutal system of chattel enslavement reigned unchecked in this part of the world for well over a century up until the Civil War.

While enslavement was declared “over,” via Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, it took until June 19, 1865, for its message and Union troops to reach the hundreds of thousands of enslaved people in Texas; and even then, not all enslaved people were freed instantly. In fact the material conditions of Black people remained largely the same in many ways via sharecropping and the system of convict leasing.

Texas history as safe haven for enslavers

Leading up to the Union General Gordon Granger’s message of emancipation to the people of Galveston, Texas, it was known that this particular state was a safe haven for enslavers. Galveston, with its deepwater port, has the oldest known police force in the state. The police protect the property and wealth of the richest people. Like many early police forces on this continent, they served as patrols for enslaved people.

Henry Louis Gates explained: “Since the capture of New Orleans in 1862, slave owners in Mississippi, Louisiana and other points east had been migrating to Texas to escape the Union Army’s reach. In a hurried reenactment of the original middle passage, more than 150,000 enslaved people were moved west to Texas.” (What is Juneteenth?, PBS.org)

After news of emancipation reached Texas, the rich still relied on the labor of those who were once legally considered their property. They did what they could to maintain that dominance and superexploitation.

This evolved into sharecropping, where the formerly enslaved still worked in the same Texas fields under similar conditions. The ruling class developed the system of convict leasing, which was designed to keep freed Black people “legally” enslaved. This was sanctioned through a clause still found in the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Under this system, the Texas Department of Corrections was formed and immediately hired out incarcerated workers to plantation owners as laborers. The workers were often Black and arrested by law enforcement for little or no reason. Convict leasing could be even worse in some ways than slavery, because those exploiting the labor of the leased people had no economic stake in their well-being or even in keeping them alive.

According to historian Robert Perkinson in “Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire,” more than 3,500 leased incarcerated workers died in Texas between 1866 and 1912 — more people than the number lynched in that period.

More people under carceral control today than during chattel enslavement

The material buildup of prisons in New York State is not identical to the origin of the prison system in Texas, but the process remains similar and certainly influenced the uprising at Attica. Also similar to conditions at Attica in 1971 is the state of prisons, jails and detention centers today.

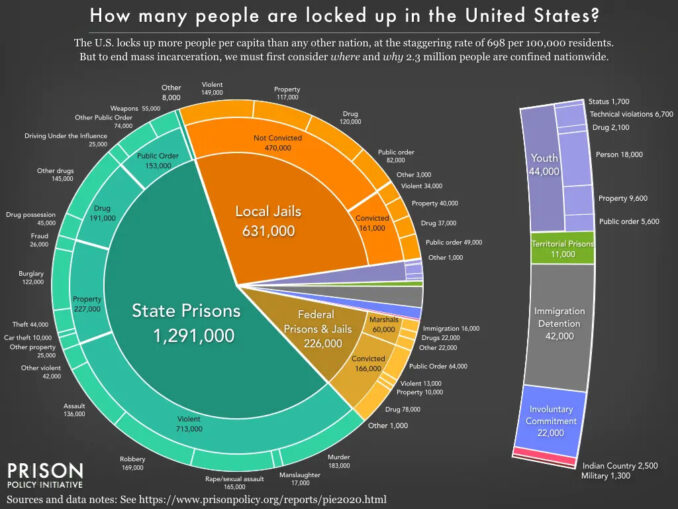

Today, more people are under carceral control than were under chattel enslavement. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, the U.S. criminal injustice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,833 state prisons; 110 federal prisons; 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities; 3,134 local jails; and 218 immigration detention facilities. This vast interlocking system of oppression also contains military prisons, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals and prisons in the U.S. territories.

Almost 2.3 million people are confined in the U.S. on a daily basis in these various facilities, but incarceration is just one piece of the much larger system of the criminal injustice system. The so-called U.S. justice system controls almost 7 million people, more than half of whom are on probation.

Mass incarceration affects more than those who are locked up themselves. Over 19 million people have been convicted of a felony in their lifetimes and face discrimination — totally legal in the U.S. — that routinely denies them the ability to vote, find housing, education, employment, among other things crucial to basic human survival. In the U.S., 77 million people have some sort of criminal record following them around. And around 113 million U.S. adults have an immediate family member who has been incarcerated.

Concentration camps for the poor

To understand why there are so many prisons, jails and detention centers, why so many people are affected by them and what purpose they serve, we need not look any further than the people most affected by these cages and those for whom this system was built.

By and large, capitalist cages are filled with people oppressed on the basis of race, gender, ability and other class-based oppressions. Black and Brown people are disproportionately locked up. LGBTQ+ people and disabled people are also disproportionately locked up compared to their make-up of the total population. And many people find themselves under multiple axes of interlocking oppressions all at once. Prisons, jails and detention centers are concentration camps for the poor and oppressed.

Law enforcement rounds up members of our class with strained historical relationships to property and locks them in prisons, jails and detention centers. Women and gender-nonconforming people’s oppression is rooted in the rise of private property. The enforcement of imaginary borders drawn by imperialists often criminalizes migrants, despite the fact that living beings have migrated across the continents for thousands of years. Under new Texas law, people with accumulated wealth who own property are deputized to oppress those without.

Confinement, imprisonment, incarceration, enslavement, whatever we call it, serve to keep the oppressed from rising up against their oppressors — those who have accumulated wealth and property off the backs of working and oppressed peoples. To abolish our current conditions living in the afterlife of enslavement, we must abolish capitalism and the rule of one class over another.

When we examine the historical origins of the prison-industrial complex, who end up in these institutions and the dire conditions people inside face during a global pandemic — we clearly see the only benefit of these institutions is for the ruling class to maintain their exploitation.

And if Attica has taught us anything, it is that oppressed peoples do not have to remain quiet as they are targeted for execution by state violence and neglect. Attica also teaches us that the solidarity from people on the outside is critical to ensuring members of our class — the working class — are not slaughtered in silence and forgotten. Attica means fight back!