Ramsey Prison Unit: The terror of Texas

By Nanon M. Williams

Nanon Williams was arrested in 1992 at age 17 for capital murder and spent years on death row. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled people under 18 could not be sentenced to death. His sentence, along with 70 others, was commuted to life and he is still fighting to prove his innocence. He has earned two associate degrees, a bachelor’s degree and a master’s degree; he was about to finish his second master’s, when the prison declared no one could earn two masters.

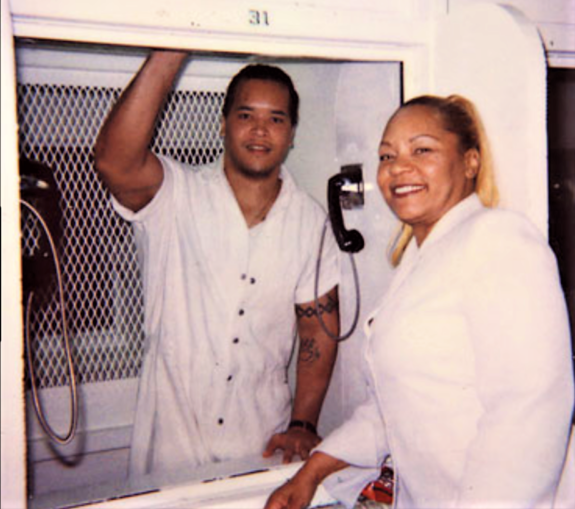

Nanon Williams with his mother, Lee Bolton, when she visited him on death row in 1998.

For decades Williams has published a newsletter, “The Williams Report,” with the help of his comrades in California. He began writing poems after going to death row — published in a 2000 book:“The Ties That Bind Us” — and has continued to write essays as well as several other books. With his autobiography “Still Surviving,” his words began to be heard across the country, and he became a leader against the Texas death row. Later Williams published “The Darkest Hour: Stories and Interviews from Death Row” exposing the inhumane and brutal conditions others have faced.

In a personal communication, he wrote, “For three decades they have stripped me of my freedom, of love, of having children, or even the simple act of attending a funeral. I now have grey hair, yet I am still young. I have survived hundreds of executions — abuse at a level the mind can’t fathom — and these people think I won’t challenge them on the BS they are doing here? Please.”

In a cover letter sent with this article, Williams expressed gratitude to Workers World newspaper for being a voice for the voiceless. — By Gloria Rubac

“Find out who made the calls, who wrote letters and made complaints, and . . .” These are the cries of the Ramsey Unit administration in Rosharon, Texas, after Gloria Rubac wrote an article in Workers World newspaper dated Nov. 19. “And what?” is now the question being asked.

The message is being sent that if inmates in Texas prisons dare to write about the brutality, violence, abuse, terror and rising death toll within its plantation-like slave camps, prisoners will be punished.

Guards are asking questions about who contributed to the article; statements are being made, and phone calls are currently being reviewed. Why? For what purpose? Do we not have freedom of speech, the right to assemble, to file a grievance or call our loved one to address what takes place, or contact the media to help us without fear of being persecuted? Are our constitutional rights so blatantly disregarded that we still face solitary confinement, risk being shipped countless miles away from our loved ones and then arrive at a new prison with the label that we are a threat?

Only a couple of years ago, Donsha Crump and I exposed the quota system for disciplinary charges here in Texas prisons. We made it public when a written order was found that illustrated in writing that it is a common practice in Texas prisons to give cases for a “gig.”

This was exposed by various activists as well as Workers World newspaper and eventually mainstream press. Pressure mounted. The prison system had to investigate and looked at various departments within all 100 or so prisons.

owever, we know we can’t expect an institution to investigate itself and come out with results against itself. That process was not only a sham, but a warning to prison administrators to simply be smarter as they prepare for gigs.

In fact at this very moment, security audits are taking place, as well as a PREA (Prison Rape Elimination Act) audit. Disciplinary cases have skyrocketed within this prison, especially with the new administration. The same practice is taking place along with the same measures and means of threatening us to keep the hell quiet.

What is a gig?

What is a gig? It is a paperwork hustle to rob taxpayers of money, justify reasons to keep prisoners incarcerated by writing bogus disciplinary cases and justify the funding needed for prisons to obtain paper trails, falsify bogus reports for hours of disciplinary hearings supposedly held and to justify money needed for security measures never used.

In other words, a paper trail is created so budgets are increased, which at the same time proves that prisoners are a threat to society.

We see front-page stories railing about crimes committed by prisoners being released, but this pales in comparison to the horrific crimes and brutal abuse the public never sees, the crimes that aren’t on the front page. For prisoners like us to dare to challenge the nature of our incarceration, who have the courage to challenge a system hell-bent on destroying us, prisoners like Mumia Abu-Jamal, Shaka Sankofa and so many others, we end up being killed or end up rotting in prisons for decades.

If we are to change as a people or as a country, we must first look inside our prisons to support those considered to be the least of us. We must look at the poor, working-class communities whose youth are destined to be warehoused in these modern day concentration camps, where people are being executed, outright killed, tortured and abused in ways that destroy who they are.

If the government treats people as less than human, what can we expect? If the system persecutes us for speaking out and organizing against racist injustice and abuse, then everyone’s rights are threatened anywhere!

The Internet has made the world a small place, and we can connect with each other globally — so let’s use that to create a better world. We can only do that by challenging the power structures that still see us as dollar signs, people who can produce profits, people who can be exploited. For a system to see us as mothers and fathers, or sons or daughters, or simply as human beings, change must come.

We must make fundamental change. We must make a systematic change! We can do it! Yes, we will!