Bolivarian soccer genius–Argentinian Diego Maradona ¡Presente!

By Danny Shaw and William Camacaro

The slightly edited article first appeared on popularresistance.org/ on Nov. 27.

The fighting peoples of the world lost a humble legend on Nov. 25. Diego Armando Maradona was 60 years old. Arguably the greatest soccer player to ever grace the pitches, the spirited striker combined unparalleled skills in his sport and an unflinching outspokenness before oppression. No other sports figure’s public statements and transformation have equally captured the changing momentum across Latin America.

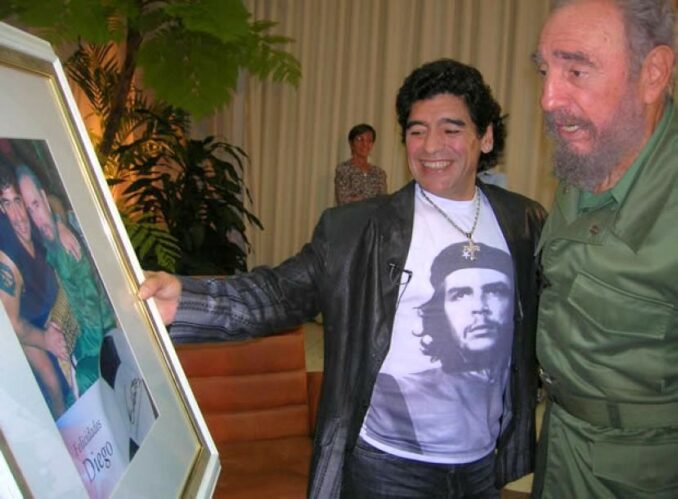

Diego Maradona, wearing Che Guevara shirt, referred to Fidel Castro as a “second father to him” following Fidel’s death in 2016

The hundreds of thousands of tributes being paid throughout the world portray a particular image: Maradona in close solidarity with the biggest progressive leaders of the social reformist wave embraced by the peoples of Latin America, the so-called Pink Tide. In fact, Maradona put to the service of the Bolivarian revolution in Latin America all his fame, his influence and his skilled legs. He embraced the peoples of Cuba, Venezuela, Brazil, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Argentina and more, by developing deep friendships with Fidel, Raúl, Lula, Evo, Hugo, Nicolás, Daniel, the Kirchners and many more.

Maradona was for the people of South America what Muhammad Ali was for Black America.

The Falklands War

Born in Lanús and raised in the oppressed community of Villa Fiorito in the outskirts of Buenos Aires; “the golden kid’s” (pibe de oro) talent from an early age fetched him million-dollar contracts first in his homeland and then in Barcelona and Napoli. (tinyurl.com/yybh3y2l)

No stranger to controversy, “the soccer god,” with his rebellious natural hair, was irreverent before elites and defiant to the core. When a Spanish player hurled racist epithets at him because of his Indigenous ancestry, Maradona headbutted him, leading to a brawl that was broadcast before King Juan Carlos, in front of 100,000 fans in the stadium, and with half of Spain watching on television.

Maradona, who was 22 years old at the time, was radicalized by England’s 1982 Falklands War assault on his homeland, known in Latin America as “la guerra de las Malvinas” and “la guerra del Atlántico Sur.” (elcomercio.pe/)

Causing untold agony and trauma, hundreds of soldiers died on both sides, and numerous veterans committed suicide for years after. Reagan’s U.S. claimed to be a “mediator,” but stayed faithful to their junior colonial partner led by the ultraconservative Margaret Thatcher.

This was the backdrop of the 1986 semifinal showdown between the two countries, without diplomatic relations, at the World Cup in Mexico City. Argentina was South America, and South America was Argentina.

During this fateful match, Maradona famously scored a crafty goal where slow-motion highlights show he illegally used his hand to redirect the ball into the English net. When the English team accused him after the game at the press conference of cheating by using his hand, he responded that “sería la mano de dios,” “it must have been the hand of god.” (tinyurl.com/y4zfrdjo)

Sports analysts applauded the “picardía” or Argentine cunningness behind the maneuver. The second goal was a miracle of human athletic skill. Maradona made a full sprint, starting on the Argentinian side, far from the English goalkeeper, and clearing a path through a minefield of English defenders, to execute a stunning goal that went down in sports history as “the goal of the century.” (tinyurl.com/yxkg6gn7)

These heroic acts sealed Diego’s destiny as an enormously popular figure combatting neocolonialism.

To beat England in Latin America was to exact revenge on the invading enemy. The soccer field was an extension of the battlefield; the arrogant English were expelled. This was the symbolic recuperation of Argentine and South American dignity.

“Patria Es Humanidad” (“The Homeland is Humanity”)

Jose Martí wrote that “our homeland is humanity.” The relationship Maradona established with Cuba was the full expression of the Cuban historic leader and poet’s words.

In 2000, an overweight and beleaguered Maradona travelled to Cuba to treat his drug addiction. Fidel Castro visited him in his worst moments and helped take care of him. The Cuban president took off his military coat and gave it to the patient. Maradona said he adored Fidel, because he was “genuine and cared about human problems that others brushed aside.”

The down-and-out “wretched of the earth” was not rejected in Havana; he was accepted, treated like a dignified human being and loved. This moment of healing was another of Maradona’s entry points into the tide of resistance that was flowing across the Americas.

The same year, Japan denied Maradona a visa because of strict laws barring anybody from the country who had a history with drugs. Today, however, past and present Japanese soccer players pay tribute to Maradona.

The frontlines in the battle of ideas

The Argentinian took great pride in the rising of Latin America’s second independence which began on December 6, 1998, with Hugo Chávez’s electoral victory in Venezuela.

In 2005, the Frente Amplio’s Tabaré Vázquez received George Bush in Uruguay in a move that was considered a betrayal by his party and the region. Bush was promoting the FTAA, the Free Trade Agreement of the Americas. “Free trade” to Maradona and millions of Latin Americans is the freedom of the U.S. and transnational capital to expand its tentacles across more of the continent.

The Bolivarian Revolution was advancing across Latin America and had recently paid off Argentina’s foreign debt. Hugo Chávez traveled to Argentina to contest the interventionist and free trade agenda of the U.S. leader. La Plata river divided the two countries and the two sides of history. Rising to the historical occasion, with Diego by his side donning a “Stop Bush” T-shirt, the Venezuelan leader famously chanted: “El que no brinca es yankee.” (If you don’t jump, you’re an imperialist.) Maradona gave credence to Evo Morales’ catch phrase: “The empire stands with the right wing, football stands with the left.”

This was the battle of ideas Castro spoke of.

A strong backer of the Pink Tide

It is perhaps difficult to appreciate Maradona’s greatness in a country whose sports loyalties are divided between baseball, North American football and basketball. In South America and Europe, soccer is king. In Napoli, restaurants have alcoves reserved for hanging religious idols. There beside them is Maradona. The mayor has announced the famed Saint Paul stadium should be renamed after one of the city’s most beloved.

Rising to the historical occasion, with Diego by his side donning a “Stop Bush” T-shirt, the Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez famously chanted: “El que no brinca es yankee.” (If you don’t jump, you’re an imperialist.)

And Maradona gave credence to Evo Morales’ catch phrase: “The empire stands with the right wing, football stands with the left.”

The mainstream press is also remembering the football titan, but consciously shying away from his political commitments. Other outlets are accusing Maradona of being anti-American. Like the political leaders he so admired, Maradona never expressed ire towards the people of the United States, but rather towards its political elites who thought they were “the county sheriff.”

Through the years of the Pink Tide, Maradona was a regular on television programs and at rallies with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, Daniel Ortega, José “Pepe” Mujica and other anti-imperialist figures of the continent. His tattoos of Ernesto Che Guevara and Fidel Castro brought a new meaning to the phrase “he wore his feelings on his sleeve.”

His program “De Zurda” on TeleSUR in 2014 with Víctor Hugo Morales, the famed Uruguayan sportscaster, combined humor, sports analysis and progressive political commentary. Last year, following a coaching win in April, he stated, “I want to dedicate this victory to Nicolás Maduro and all Venezuelans who are suffering. These Yankees, the sheriffs of the world, think just because they have the world’s biggest bomb they can push us around. But no, not us.”

Those who had the honor to meet Dieguito remember him as a people’s person who was always accessible. Though he had his own personal struggles, he never wavered in his commitments to elevating the voices of the poor and defending the underdog. Yesterday, on the fourth anniversary of Fidel Castro’s passing, one of his students and admirers joined him in eternity, having left so much for us all to savor and learn from.

Danny Shaw and William Camacaro are the senior research fellow and senior analyst, respectively at the Council on Hemispheric Affairs.

Fred Mills and Patricio Zamorano contributed as co-editors.