Professional athlete strikes inspire other workers

The following article is based on a talk given during a Sept. 10 webinar, “Workers Defend Black Lives,” sponsored by Workers World Party. View webinar at tinyurl.com/y6m9z593.

National Football League football is the most popular U.S. professional sport, with 32 teams at a combined worth of $91 billion.

So when Colin Kaepernick first took a knee four years ago to protest police brutality and systemic racism, during the playing of the reactionary national anthem, he took on 32 of the world’s richest team owners.

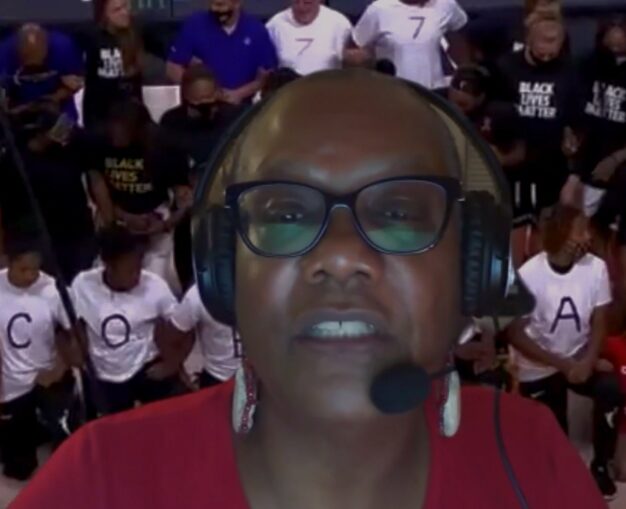

Los Angeles Lakers, including LeBron James, take a knee, inspired by Colin Kaepernick.

These bosses, with Trump’s support, collectively “blackballed” Kaepernick from playing in the NFL. They claimed his actions would hurt their bottom line, saying fans would be turned off from watching NFL games if any players followed in Kaepernick’s footsteps.

The Washington Post released a poll on Sept. 10 showing at least 56% of football fans support NFL players taking a knee. A similar poll back in 2018 by the Wall Street Journal found only 43% fan approval. This is an important barometer indicating a significant political sea change, especially for a sport that has been so militarized and conservatized over the decades.

Throughout U.S. society there has been a dramatic shift in terms of how police are viewed, especially since the public lynching of George Floyd in Minneapolis. On May 25 people worldwide saw a Black man being tortured for almost nine minutes by four white police officers. One kept the full weight of his knee on the neck of Floyd, who was screaming “I can’t breathe” and “I want my mother.”

Ever since, millions of people have been in the streets, almost daily, demanding to defund and even abolish the police in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. Confederate statues, monuments and other visible pro-slavery images have been torn down or forced down by the masses.

Athletes strike for Black lives

The protests have had a tremendous impact on athletes in pro sports, beginning with the National Basketball Association and the Women’s National Basketball Association.

In late August, following the horrific police shooting of Jacob Blake, a 29-year-old Black father of six shot seven times in the back in Kenosha, Wis., the Milwaukee Bucks carried out a heroic wildcat strike by refusing to play an NBA playoff game in Florida. Other NBA teams, in a show of strong solidarity, also refused to play over the next three days.

The WNBA refused to play games for one to two days and every WNBA team locked arms together in solidarity. This prompted players in Major League Baseball, National Hockey League and Major League Soccer, that are a majority white, to refuse to play as a team or as individuals. This is an important step toward building anti-racist unity.

The number one tennis player in the world, Naomi Osaka, wore seven different face masks before her tennis matches with one name on each – Ahmaud Arbery, Philando Castile, George Floyd, Trayvon Martin, Elijah McClain, Tamir Rice and Breonna Taylor – before winning the 2020 U.S. Open on Sept. 12. She was thanked by the families of Arbery, Floyd and Martin for using her platform to raise BLM awareness of police violence and systemic racism. Osaka refused to play a match in late August before the U.S. Open in solidarity with the Bucks’ action.

Naomi Osaka at U.S. Open Sept.8

Why are athletes included in this webinar on workers supporting Black Lives Matter? Sports are immensely popular in the U.S., whether professional or amateur. But what gets lost is that athletes, whether they receive millions of dollars or hundreds of thousands of dollars in salary, are workers.

They are gladiators well paid to entertain the masses. In all professional sports, players are represented either by a union or an association that negotiates with the bosses for a collective bargaining agreement. And now growing numbers of college athletes are becoming more conscious as workers and want to be organized.

Worker labor, worker power

It is the players who fill the arenas and the stadiums, not the bosses – who get super-rich in the billions of dollars from the ticket sales, concession sales and especially TV revenues. As with workers in a plant or restaurant, the players’ labor – in the form of skills and talent – produces a commodity, a thing of value that can be bought and sold.

It is from workers’ labor that the owner derives profit. If a worker works eight hours, only part of that time covers the cost of the worker’s wage. The rest of the time is unpaid labor and it is from this that the owner gains surplus value. As a class, the bosses keep the surplus value created by the global working class as profits, resulting in an immeasurable gap between rich and poor, and workers feeling disempowered. Building workers’ assemblies can turn this around.

Once they refused to play, NBA players felt their power by withholding their labor. With the growing capitalist economic war on workers, spurred on by the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a rising chorus of workers talking about a general strike, harkening back to the general strike of millions of migrant workers on May Day 2006. This general strike would be even more classwide, including both economic and political demands and building off of a one-day national strike led by “essential” workers but also inspired by NBA players.

As a Sept. 9 op-ed in the New York Times stated, “In May, essential workers at Amazon, Instacart and other e-commerce and delivery companies staged a one-day national strike demanding better protections and higher pay. In July, thousands of workers from a range of industries walked off the job in support of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“At the other end of the pay scale, professional basketball players got their league to adopt a number of social-justice initiatives after they went on strike last month to protest racial inequality and police brutality. Last week, several large unions announced they are considering authorizing work stoppages to push for concrete measures to address racial injustice.”

The bourgeoisie, as heard through their mouthpieces like the Times, fear what is on the horizon: even bigger class-wide battles to come.

Monica Moorehead

The writer’s father, Isaac Moorehead, was a title-winning coach of men’s and women’s basketball teams for over 40 years at historically Black colleges and universities.