COVID-19 devastates Indigenous communities

By Eno Flurry

This article is written in the colonized lands of the Comanche, as well as the Tonkawa Nations — now the state of Texas. Workers World supports the right to self-determination of, and promotes full solidarity with, Indigenous struggles.

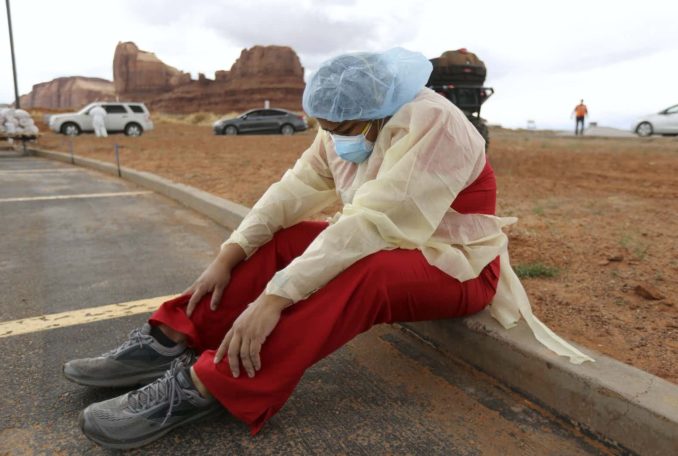

From Indian Country Today: ““My feet hurt,” says Denise Begaye, an X-ray technician with the Monument Valley Health Center, as she sits on a curb and takes a break from COVID-19 testing outside of the center in Oljato-Monument Valley, San Juan County on Thursday, April 16, 2020.”

While Black and Latinx households are twice as likely as white households to lack indoor plumbing, Indigenous households are 19 times more likely than white people to not have indoor plumbing or access to clean water at their residence, especially in the Four Corners of the Southwest. (tinyurl.com/yao3b9jh) For the Diné or Navajo Nation which covers parts of New Mexico, Colorado, Utah and Arizona, much of the groundwater has been contaminated by 521 abandoned uranium mines and is undrinkable. For many in the Navajo Nation, it is the closest, most available water and is given to the animals to drink — the same animals that they will one day eat. (tinyurl.com/reqy657)

Just this alone — the lack of access to clean water on a daily basis — is enough to exacerbate other issues, such as illnesses including cancer. Four Indigenous researchers found in a new study that the rate of COVID-19 cases per 1,000 people on a reservation is more than four times higher than in the United States as a whole. (Indian Country Today, April 25) And many Diné homes also lack electricity.

While the Native population only comprises 6 percent of the total population of New Mexico, Gov. Michelle Grisham reported April 12 that 25 percent of the state’s COVID-19 cases were Indigenous people, including the Diné and several Puebloan nations. While some of the discrepancy is due to higher rates of testing by the Diné /Navajo Nation compared to that in neighboring states, that alone cannot explain the fact that the rate of infection on the Navajo reservation is 19 times that in the state of Arizona. As of April 26, the number of cases in the Navajo Nation had reached 1,716, with 59 deaths. (Navajo Times, April 27)

Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer self-isolated after exposure to a COVID-19-positive health care worker in the course of their work. They initiated a 57-hour curfew over Easter weekend, which excluded essential workers and has been extended for every weekend until early May.

Pine Ridge Reservation is another severe case where they have closed their borders to tourists and other nonmembers of that Native nation driving through it. This is in South Dakota where Gov. Kristi Noem still refuses to issue a shutdown order, despite the huge COVID breakout at the Sioux Falls, S.D., Smithfield pork factory.

Nick Estes, Ph.D., a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, noted that “COVID-19 is taking its toll on Indian Country — not because Indigenous people are more susceptible to the virus for cultural reasons (as reported by some media outlets), but because of a chronic lack of underfunding of our healthcare services and, you know, genocidal colonialism.” This is nothing more than a modern version of colonial white supremacy.

Diné molecular biologist Wilfred Denetclaw said possible reasons for the high COVID death rate in the Navajo Nation include the need for many people to travel to hot spots such as Albuquerque “to buy what they need, and then they bring the virus back.”

Circumpolar Inuit communities in Alaska, who are dealing with unsafe drinking water and lack of sewage infrastructure, face a threat of COVID-19 infections similar to that of the Navajo Nation. The Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation estimates that more than 3,300 rural homes occupied year-round do not have potable water. All this is due to the ongoing neglect of Indigenous communities and their health and safety by the federal government.

Another issue faced by Indigenous Nations is a housing crisis. While we are told to practice social distancing by the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies, in many Native communities this is simply an impossible task. A report from Wyoming Public Radio about the Wind River Reservation shows overcrowded, multigenerational households, as many share homes with their relatives, just as many other poor families do.

An additional crisis affecting some of the Native reservations is the closure of one of the few sources of tribal income — casinos. A Harvard research team has estimated that upwards of nearly $50 billion in annual wages and benefits have been lost due to closures of gaming and nongaming enterprises that many reservations rely on for income to meet their needs.

This mass layoff of Native workers is leading to loss of insurance coverage, where that exists, in addition to the vastly underfunded Indian Health Service, and the growth of debt in areas in and outside of the reservations. These casino-generated funds are used for what would normally be funded by state or local governments: law enforcement, public safety, social services and educational support. So let’s break down what the tribal governments stand to lose: According to the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, $127 billion in national output; 1.1 million jobs, with 915,000 workers who are non-Native, while 211,000 are Native; $49.5 billion in worker income; $12.5 billion in Tribal government revenue; $9.4 billion in state and local tax revenue; and $15.9 billion in federal tax revenue.

These numbers represent the razor’s edge on which Native nations in the occupied U.S. are constantly balancing in their struggle against the neglect and violence of the U.S. government.

And all this reminds us of the importance of the struggles for clean water, such as the recent struggle at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline and the struggle in Flint, Mich. How can you have good health care if you do not have clean water?