Saluting 3 women labor leaders, past and present

When one thinks of women labor leaders, names from the past like Lucy Gonzalez Parsons, Mother Jones, Elizabeth Hurley Flynn and Clara Lemlich come to mind. But two women born in the 20th century were more recent trailblazers in the labor movement and another one is on her way to make history.

Addie Wyatt, first African-American woman elected officer in her local

Addie Wyatt

Addie Wyatt (March 8, 1924 — March 28, 2012) was elected president in 1954 of Local 56 of the Packinghouse Workers (UPWA) — the first African-American woman to hold a senior office in the U.S. labor movement. Born in Brookhaven, Miss.,Wyatt was a labor leader, pastor and tireless fighter for civil rights and women’s rights in Chicago, birthplace of May Day in the late 1800s.

President Kennedy appointed her to his Commission on the Status of Women in 1962. She was a founding member of the National Organization of Women in 1963, the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists in 1972 and the Coalition of Labor Union Women in 1974. The Addie Wyatt Center for Nonviolence Training, established in 2016 to carry on her legacy, offers workshops, retreats and programs on Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolence theory and practice in Chicago area schools and agencies serving youth.

By 1956, she and her like-minded spouse, Claude S. Wyatt Jr., began working with Dr. King to raise funds for the Montgomery Improvement Association. Wyatt organized Black, white and Latinx laborers in UPWA to win “equal pay for equal work” in many contracts well before the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

During the ’70s, Wyatt worked in the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists to ensure that Black workers could “share in the power of the labor movement at every level.” As chair of CBTU’s National Women’s Committee, Wyatt helped AFL-CIO affiliated unions open up leadership positions to Black women.

Wyatt furthered that through the Coalition of Labor Union Women: “Racism and sexism are economic issues. It was very profitable to discriminate against women and against people of color. I began to understand that change could come, but you . . . had to unite with others. This was one of the reasons I became part of the union.” (calaborfed.org)

CLUW was an important step forward because it spoke for women who felt left out of the white-dominated women’s movement.

Wyatt fought for human rights on three fronts: as a laborer, as a woman and as an African American.

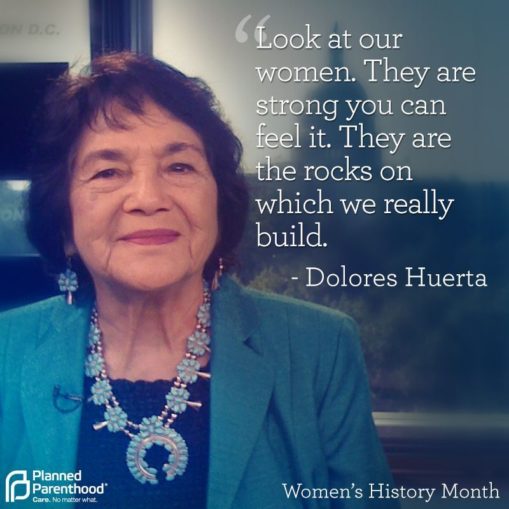

Dolores Fernández Huerta, Chicana labor leader, civil rights activist

Dolores Huerta

Born April 10, 1930, in New Mexico, Dolores Huerta cofounded the National Farmworkers Association in 1962 with Cesar Chavez. (It became the United Farm Workers in 1966.) A proud Chicana, Dolores’ father was a miner and a labor organizer. After her parents divorced, her mother ran a hotel in Stockton, Calif., and took in anyone who needed shelter, even if they couldn’t pay. Huerta says both parents gave her their strengths — fighting for rights and abundant compassion.

Working as a community organizer after college, where she was introduced to nonviolence, Huerta and Chávez shared a vision of organizing the poorest, most oppressed Chicano/a workers. Huerta helped organize the Delano grape strike in California in 1965. When the struggle for unionization ebbed there, Dolores suggested a national grape boycott. Leading it in New York City, she credits the Puerto Rican and Black communities with providing immediate, sustained support. After the strike succeeded, she was the lead negotiator for the workers’ contract.

The cultural emergence of the Chicano Power movement in the Southwest and the founding of the environmental justice movement are offshoots of the farmworkers’ struggle. Their life-and-death fight against pesticide poisoning helped outlaw DDT in the U.S. in 1972.

A turning point came in Dolores’ life in 1988 when she was ruthlessly beaten by San Francisco cops protesting a George H.W. Bush meeting. During an extended hospital stay and recuperation, her 11 children rallied around her 24/7. All of them have proudly followed in her footsteps.

After César died in 1993, Dolores resigned from the UFW a few years later. Thanks to a $100,000 award in 2002 for her life’s work, she set up the Dolores Huerta Foundation for community organizing, which is now run by two daughters.

Huerta has received many awards recognizing her contributions in the fight for rights for workers, im/migrants and women, including one from the Eugene V. Debs Foundation. She was the first Latina inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993. April 10 is Dolores Huerta Day in California.

One award she treasures is being known for the slogan “Si se puede” — “Yes, we can.” Not only does it power the movement for $15 and a union, but all movements striving for justice and equality.

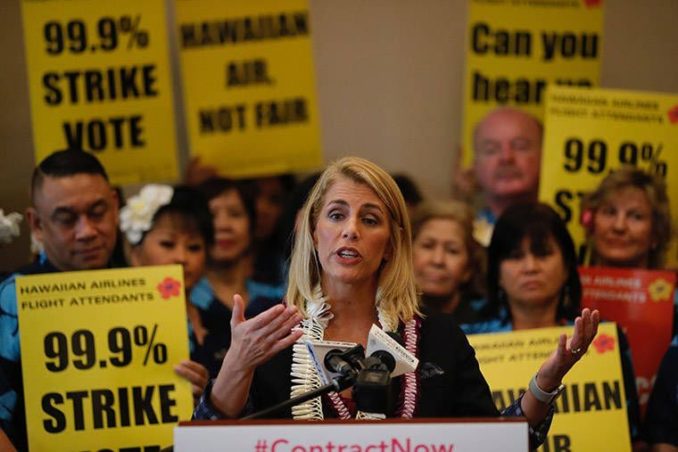

Sara Nelson, activist head of 50,000 flight attendants in 20 airlines

Sara Nelson

A United flight attendant since 1996, Sara Nelson, international president of the Association of Flight Attendants-Communication Workers (CWA), is in the running to become the next head of the AFL-CIO. She has strong credentials: To end weeks of Trump’s disastrous government shutdown in 2018-19, she called for a general strike on Jan. 20. Nelson argued that Transportation Security Administration officers and air traffic controllers were swamped by the terrible stress the shutdown was placing on them, and that was eroding the safety of the entire industry. The shutdown ended the next day.

Calling for the airline industry to address the COVID-19 crisis, Nelson told CNN March 7 that a government exception is needed so airlines can mount “full-size hand sanitizer in the galley area and near lavatories” on airplanes. Demands include installation of “hand sanitizer stations in airports and on planes” and that airlines raise aircraft-cleaning standards and cover “all medical costs and lost wages for workers exposed in the course of work.” Go, Sara Nelson!