Black labor: From chattel slavery to wage slavery, Part 2

The following is excerpted from Chapter 2 of Marcy’s “High Tech, Low Pay: A Marxist analysis of the changing character of the working class,” first published in 1986. Note that a few selected words have been updated to reflect current usage. Marcy is the late chairperson of Workers World Party. “High Tech, Low Pay” is available as a free download at workers.org/marcy.

The South was a slavocracy based on an ancient mode of production within the geographical confines of a new world social order, the bourgeois social order, with its own mode of capitalist production. One of the fundamental differences between the bourgeois mode and older modes of production so eloquently brought out in the Communist Manifesto is that “The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society.” 13

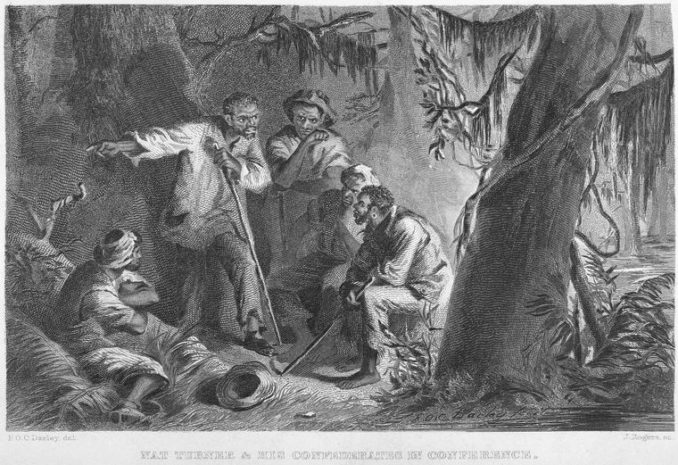

Nat Turner plans heroic slave rebellion, which he led in Virginia in 1831.

How does this stack up with the Southern slavocracy? Marx continued, “Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form was . . . the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes.” The South tried to retain the old slavocracy not only in unaltered form but in extreme rigidity. It was therefore on a collision course with the new bourgeois order, with the process of capitalist production and its tremendous growth in the North.

Slavery vs. capitalist production

Another and more flagrant contradiction was that one of the fundamental characteristics of the capitalist mode of production is wage slavery, which means a free proletarian, that is, a worker free to sell his or her labor on the capitalist market. Capitalist production and the extraction of surplus value in the interest of further capitalist accumulation is virtually impossible without a free working class, free to be exploited and oppressed, free to be unemployed. Chattel slavery was thus thoroughly incompatible with wage slavery.

Slavery as an economic institution has everywhere proved itself uneconomical. This is especially true when it depends on one great crop such as cotton, with diminishing reliance on sugar, rice and other products. The South was turning into a monocultural economy.

Over all, the spectacular leap in technology on which the Southern planters depended so heavily to maintain slavery was only one of many scientific and technological developments in an era which was rapidly turning them out in greater and greater numbers. In this respect the South was falling far behind the North.

The North was making all the great strides in science and technology. It built up great universities which became centers for basic research. Whatever prominence the South had had in science in the earlier days, it was losing to the North. Seen in terms of the contemporary struggle in technology of the U.S. against Japan and Western Europe, the South was steadily losing ground to the North in what we would call today the technological race.

As a competing form of economic and social system compared to the social system based on capitalist production, slavery was hopelessly out of place and had no chance, save by the use of sheer force. Slavery was static, fixed and extremely rigid in its form of production. It was also characterized by the most outlandish forms of cruelty and brutality.

The capitalist system, on the other hand, while certainly not characterized by either compassion or humanity, was nevertheless “revolutionizing” its means of production, that is, it was advancing science and technology. The change from chattel slavery to wage slavery was a profoundly revolutionary change, a tremendous social transformation. But historically it constituted a change in the form of exploitation, not its abolition.

Thus we see that while the first phase of the scientific-technological revolution brought fabulous profits to the South and gave it the power to expand, it ultimately undid slavery. Just as technological change undermined the Southern slavocracy, so will it make obsolete the present industrial financial plutocracy with its system of wage slavery … .

Black labor today

Extrapolating from the population figures provided in the 1986 annual report of the National Urban League on the “State of Black America,” there are about 28 million Black people in the United States. That’s larger than most African countries and larger than most middle-sized countries represented in the United Nations.

By always referring to Black people as a minority, the bourgeois press obscures the class significance of the Black population, which is overwhelmingly working class and which, therefore, especially when taken together with the Latinx, Asian and Native population, adds a very significant dimension to the whole character of the working class here.

To regard the Black struggle strictly from the viewpoint of minority-majority is to lose much of its profound social and political implications. What should interest working-class students of the Black struggle, however, is that even these figures, which are probably understated, disclose a social viability which has strong revolutionary potentialities given the conditions we believe are developing that will give a fundamentally altered social composition to the working class.

To understand the current state of Black labor in the United States, it is necessary to look first at the mass migration of Black people to the North which took on momentum early in the 20th century and reached considerable proportions at the end of the First World War. Mass production industries in the U.S. like auto (especially Ford) and steel were in a period of high capitalist development. When this culminated in the First World War, it opened the gates of some industries and fields of economic endeavor to Black labor, notwithstanding rank discrimination and entrenched racial barriers.

These were not relaxed. Instead artificial classifications were created so that Black workers doing almost exactly the same work as whites got far lower wages. Nor were barriers lifted in the skilled trades and American Federation of Labor craft unions. These were as rigidly racist in their approach as they had been before the First World War. But Black labor continually found ways to gain skills and get skilled jobs despite government, employer and union racial discrimination.

It should always be borne in mind that even the first boatloads of enslaved people who arrived in this country from Africa brought with them useful skills which were developed even in slavery times. In cities like New York and Philadelphia, before the mass migrations from Europe started, there were a considerable number of Black workers in industry who had developed skills. But as more and more white labor from Europe became available, Black workers began to be relentlessly driven out of industry.

These mass migrations from Europe undermined whatever leverage the Black workers might have had in industry notwithstanding discrimination. Things got more and more difficult for them.

Capitalism, as the involuntary promoter of the development of the working class, also caused the mass migration of Black agricultural workers from the South to the North. Notwithstanding the racial barrier or the unemployment as a consequence of the capitalist economic cycle, more and more Black workers got into Northern industry even as the pool of Black unemployed grew.

That most of the central cities of the North, and now some in the South, have a majority or a very large minority of Black people is objectively due to the transformation of capitalist industry with the First and Second World Wars. World War II in particular was a much longer war for the U.S. and entailed the construction of many defense facilities. In fact, the entire U.S. industrial apparatus was converted for war purposes and for the first time full employment became an artificial phenomenon dependent on war spending.

These two objective factors — the First and Second World Wars — also found an echo beginning in 1950 with the Korean War. In the early 1950s and again during the Vietnam War employment was artificially propped up by the continuing growth of the defense industries.

If today in cities like Detroit, Chicago, Newark, Philadelphia, New York, Atlanta, Memphis and Birmingham there are large Black populations with some political power, it is not due to any attempt by the ruling class to ameliorate the condition of Black workers or to lighten the burden of discrimination. Rather it comes as a result of objective development arising out of the organic functioning of the capitalist system and the inevitability of imperialist wars and military interventions abroad. This is not to say that the whole industrial structure of the U.S. is due entirely to imperialist wars, but without them it is difficult to conceive how there could have been such a rapid social transformation in the condition of Black and also white workers.

The mass migration from the South — and back to the South, especially during times of unemployment — is among the objective factors affecting the development of Black labor. The subjective factors arise from the freedom struggle, especially the struggle of the 1960s … .

The Black Freedom struggle

It is utterly impossible to understand the contemporary role of Black workers in this country and particularly their situation in the trade union movement without considering them in a broader political framework. A study of Black labor, especially over the last 25 years, that omitted the general political struggle, the freedom struggle of the Black people as a whole, would make for a very constricted and even distorted view of both the great achievements of Black workers in the trade union movement and the equally great, if not greater, drawbacks of their situation.

Racism has permeated every layer of capitalist society; the trade union movement from its earliest times up to the present has been permeated with chauvinism and vicious discriminatory practices. The trade unions are the most formidable working-class organizations in the country. Aside from temporary retreats and taking into account the long duration of the political reaction, they are bound to become organs of the great struggles for emancipation from both racist oppression and capitalist class exploitation.

But all of this has to be considered in the broader arena of the overall political struggle of Black people, in which the trade unions have certainly been a significant part, but only a part. In reality, what happens there is a reflection of what is going on in the Black struggle as a whole. The great battles of the 1960s and 1970s in particular must be considered in evaluating and analyzing how this reflected itself in the unions.

Just to take one example out of many: In April 1969, some 500 Black workers shut down production at the Ford plant in Mahwah, N.J., for several days. The workers walked out because a foreman called one of the workers a “Black bastard.” Although the official United Auto Workers leadership urged the workers to return to their jobs, they nevertheless stayed out until the foreman was ousted from the plant. This was the famous so-called wildcat strike at Mahwah organized by the United Black Brothers, and it represented a significant victory for all the workers.

If this significant victory for the UAW at that period is seen only in the trade union framework, it could present an oddity. But when seen in the larger framework of the overall Black political struggle, one gets a far truer measure of its significance for the local struggle as well as nationally.

There were other significant developments in the UAW that came on the heels of the great 1967 rebellion in Detroit and ushered in a series of electoral victories for the Black workers in the UAW. “Suddenly the UAW leadership stopped the practice of mobilizing opposition to Black candidates in local elections. Within a few months after the formation of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers, Black workers were elected as presidents of Local 900 (Ford’s Wayne plant), Local 47 (Chrysler Detroit Forge), Local 961 (Chrysler’s Eldron Gear), Local 7 (Chrysler), Local 51 (Plymouth), and even Local 1248 (Chrysler Mopar), where only 20 percent of the plant’s 989 workers were Black. A Black was elected for the first time as vice president of Briggs Local 21. …”16

Before the Mahwah struggle took place, there were a considerable number of political rebellions and insurrections of Black people. There was the Harlem rebellion, followed by Watts, Newark, and Cleveland, to name only a few, and of course the largest of the mass insurrections took place in Detroit. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King in 1968 there were a total of more than 500 rebellions throughout the whole country.

How then can the struggles of Black workers for equality be seen as strictly trade union struggles? Few if any of the very significant gains made by Black workers could have been attained without the so-called outside struggle, that is, the general political struggle put up by Black people. That was the real catalyst, the basic generator for the trade union gains, many of which were not only vital but indispensable, considering the long and difficult task to attain equality which still goes on.

What is said about the Black struggle applies equally and to some extent even more to the Latin struggle, the women’s struggle and the [LGBTQ2+] struggle. Any gains made in the unions must be related to the broader struggles which generated them. It would of course be fruitful to speculate on how different it could have been had the struggles been initiated by the trade union movement rather than being forced upon it. But this is the music of the future, not of the past.

There are about 110 million workers in the U.S. today. In the mid-1980s, only about 17.3 million belonged to unions, as we’ve discussed earlier. However, there can be no doubt that the union movement will become the fundamental lever for working-class struggle. The anti-labor offensive which has been sweeping the country for several years is bound to produce one of the truly great upsurges of the working class, and this time the union movement will not be in the rearguard but in the vanguard of the struggle as regards Black, Latinx, Asian, and Native people, women and [LGBTQ2+ people].

The tardiness of the working-class response to the offensive of the ruling class in the face of such profound political and social reaction can be explained in part by the lack of a mass political party of the working class. The response from the working class, both organized and unorganized, is likely to come as the result of spontaneous outbreaks which will take the form of trade unionism but not necessarily in the way the trade union officialdom presides over the union movement. What more concrete form it will take we have to leave for events themselves to reveal.

Suffice it to say that the very intensity of the political reaction, generated by the Reagan administration and prepared earlier by the Carter administration and its predecessors, has created the conditions for a tumultuous social upheaval, not a controlled one that could be easily manipulated by contemporary bourgeois politicians and the trade union bureaucracy. The very tardiness in preparing a party of the working class, which in Europe and other areas has taken generations to build up, makes inevitable that the pent-up rage at the oppression and exploitation endured by all strata of the working class will break out in another form. It would seem to emanate most easily from the workplace and from the vast pool of unemployed. The special oppression of women, Black, Latinx, Asian, Arab, Native and [LGBTQ2+] workers will make them a magnet for one another.

A former science adviser to Reagan in late 1985 told a Cable News Network (CNN) interviewer that “unemployment in Western Europe constitutes the greatest danger to Western civilization.” Of course, it’s true! But not only in Europe.

The capitalist “recovery” here in the U.S. has been taking place amidst some 15 million unemployed, if comprehensive calculations are made. Social peace cannot be maintained on such an explosive material base.

References

13. Marx, Karl and Frederick Engels, “Manifesto of the Communist Party,” Vol.

16. Foner, Philip, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981. International Publishers (New York, 1982), p. 417.