Class war at GM

The strike of autoworkers at General Motors is just over a week old, but already the class lines are clear. At more than one location, pickets were injured by delivery drivers trying to drive through the lines and into the plants. Police have harassed pickets, and in Spring Hill, Tenn., strikers were arrested after police asked them to move.

Almost immediately GM bosses took a hard line against the striking workers, abruptly cutting off health insurance. Normally, health benefits would not be allowed to lapse until the end of the month, at which point if the strike is not settled the United Auto Workers union would pick up the costs.

GM’s shock-and-awe strategy left workers, some in the middle of medical treatments, with no health insurance while they waited to sign up for union-provided benefits. One member literally woke up from surgery and was told her bill would not be covered. Others were denied chemotherapy treatment or taken off lists for organ transplants. Pregnant workers were anxious as their delivery dates drew near.

The workers can put the pressure on the bosses, too. The strike is reportedly costing GM as much as $75 million a day.

The rank and file want a contract that protects health benefits, keeps plants open, improves wages and bonuses, and gives “temporary” workers a path to permanent, full-time positions.

The company’s offer, made just hours before the Sept. 15 strike deadline, demands hourly workers pay thousands more a year for health care, offers nothing to temporary workers and actually increases the number of lower-paying jobs contracted to third parties or assigned to the GM Subsystems division.

Striking alongside GM workers at five plants are 850 janitors and maintenance workers, who are UAW members employed by Aramark. They do work that GM workers had performed before these jobs were outsourced in 2007, but for little more than half what GM janitors had been paid. Only after five years do Aramark workers make as much as $15.18 an hour for dangerous work using high-pressure washers.

When they walked out, 24 hours before the GM strike started, their chant was “What do you want? Respect.” Aramark workers have been without a contract for a year and a half.

Over the years GM, Ford and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles have contracted more work out to companies like Aramark. GM also created “GM Subsystems,” whose Brownsville, Mich., battery factory pays much lower wages than other GM plants.

In Lordstown, Ohio, GM wants to replace a recently closed assembly plant with a battery manufacturing facility run by an as-yet-unnamed, but lower-wage, company—perhaps a third party or GM Subsystems.

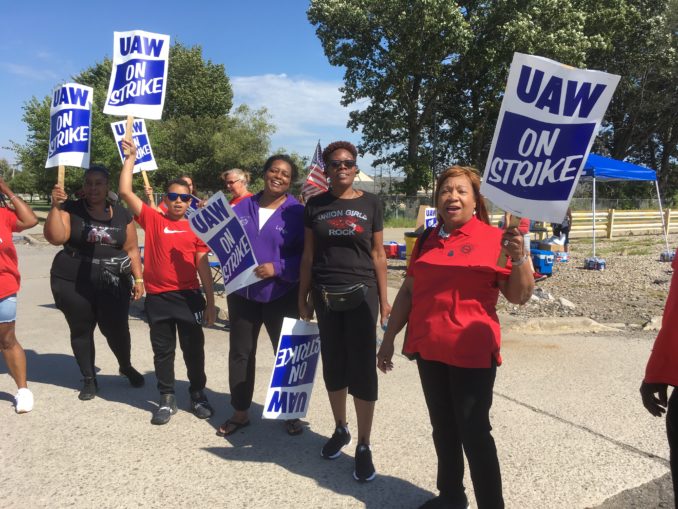

Solidarity all around

The strike has been successful in shutting down production at GM. As a result, a large percentage of GM’s Canadian workers, who are not on strike, have been laid off. Yet Canadian GM workers describe their widespread solidarity with strikers in the U.S. From Brazil, too, autoworkers have sent messages of support.

Dozens of Ford and FCA workers joined pickets Sept. 19 outside the Warren, Mich., transmission plant, which is nearly closed. On Sept. 22, after a power outage caused the union meeting to be unexpectedly cancelled, a delegation of Local 869 members, who work at FCA Warren Stamping, walked across the street to picket with Local 909 members outside the transmission plant.

Just hours into the strike, FCA workers at the Toledo, Ohio, Jeep assembly plant organized a 400-strong car caravan that drove past the picket line and honked support. The sound of solidarity honking continues nonstop, day and night at every picket line.

Ford and FCA workers know that if the strike wins a decent contract at GM, it will give them leverage to get the same. On the other hand, if GM breaks the strike, it will set the workers back at the other major auto companies. Whatever happens with the GM strike, these workers could also find themselves on picket lines fighting companies that are just as profit-driven as GM.

Other unions are supporting the strike by showing up on picket lines, delivering food to the strikers and sending solidarity messages. The Teamsters made it clear from the onset that their union drivers would not cross a UAW picket line. Even local small businesses are donating and giving discounts to strikers.

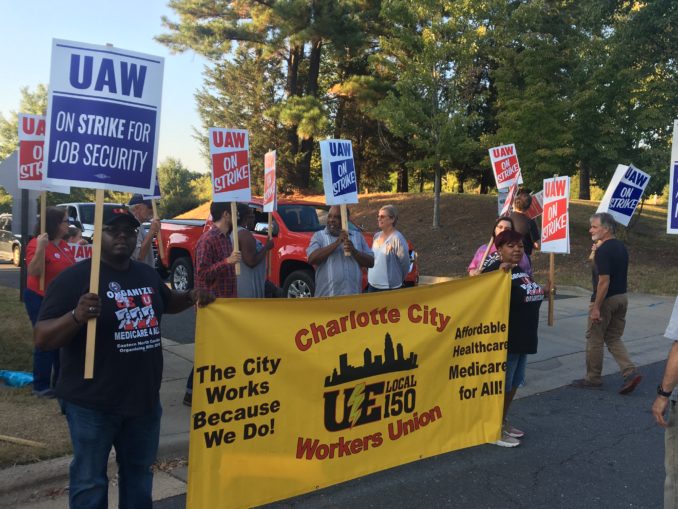

Strike reaches beyond autoworkers

In taking on GM, autoworkers are fighting for more than just the needs of UAW members. They see the growth of a temporary or part-time workforce throughout the economy. They know their strike can impact the lives of all low-wage and contingent workers.

The critical fight to protect health care will be pushed forward if the strike wins, or it will be set back if it loses. Health care for profit means costs for prescriptions, hospital stays, insurance, etc., could rise to whatever the market will bear. Instead of demanding lower prices from fellow-capitalist medical profiteers, the auto barons want workers to pay more for medical care — much more.

Workers are angry that even though the company has made record profits — $35 billion in four years — it won’t give an inch when it comes to workers’ righteous demand for equal pay for equal work. GM — whose CEO Mary Barra’s salary was $22 million last year — wants to maintain the system of tiered wages, with “traditional” (first tier), “in progression” (second tier) and “temporary” (third tier) all working side by side doing the same work for different wages. GM uses tiers to foster differences among the workers, with the end goal of making all the workers lower tier.

What GM just paid out in quarterly shareholder dividends — over half a billion dollars — is double what it claims to pay quarterly for health care benefits.

This first strike against an auto company since 2007 is the biggest strike in the country in 12 years; nearly 50,000 workers are out. This worker action is not happening in a vacuum. Since the militant 2018 West Virginia teachers strike, the number of strikes countrywide has risen dramatically.

The growing number of strikes shows that the working class is fed up with capitalist greed. Polls show support for unions is at a high of 60 percent, even though only 10 percent of U.S. workers have the benefit of union representation.

The stakes are high, and the battle lines are drawn. Which side are you on?

Grevatt recently retired from FCA after 31 years. She serves on the executive board of UAW Local 869.