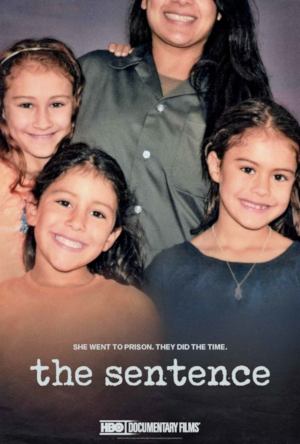

‘The Sentence’: An intersectional view of mass incarceration

In January, HBO purchased the rights to the independent documentary “The Sentence” following its success at the Sundance Film Festival. The documentary debuted on HBO and various streaming services in October.

In January, HBO purchased the rights to the independent documentary “The Sentence” following its success at the Sundance Film Festival. The documentary debuted on HBO and various streaming services in October.

Produced by rookie filmmaker Rudy Valdez, “The Sentence” spans a nine-year period from 2007 until late 2016 as it chronicles the story of Valdez’s sister, Cindy Shank, a Mexican-American woman and Michigan resident. In 2007, Shank was arrested and later convicted for conspiracy to distribute cocaine.

From the late 1990s to the early 2000s, Shank lived with her late boyfriend, a drug dealer, until his murder in the early 2000s. Originally taken into custody, charges against her were dropped until the Justice Department decided to reopen her case.

As explained in “The Sentence,” a person can be charged with conspiracy solely for being knowledgeable about the commission of a crime without reporting it. Under mandatory federal sentencing guidelines, Shank was then sentenced to 15 years in federal prison. Confused and feeling helpless, Valdez and his extended family were, nevertheless, able to use the power of video to fight against Shank’s unjust incarceration.

The reaction to “The Sentence” by popular critics has been overwhelmingly supportive. Yet, while supportive of Shank and the Valdez family, the reviews have also bordered on justifying the incarceration of the multitudes of people imprisoned for drug offenses: primarily people of color.

Consider the Washington Post review by Steven Zeitchik. He argues that “‘The Sentence’ puts a tearful human face on prison injustice.” Later he hopes that the documentary does for the movement against mandatory minimums what “An Inconvenient Truth” did for climate change. This liberal strategy of moral persuasion against mass incarceration is not novel. It instead represents the similar strategy taken by Europeans and white U.S. reformers against chattel slavery in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The problem is that to suggest there is now a “human face” on mass incarceration seems to underscore that the other faces — including those of many Black men imprisoned on drug charges — are not human. The story of Shank, or even Alice Marie Johnson who was released earlier this year after Kim Kardashian’s appeal to Donald Trump, is presented as an exception to the rule — sympathetic characters who do not deserve to be treated as the others. Therein lies the contradiction in how mainstream journalists have received the film.

Importance of intersectional analysis

Popular reviews of “The Sentence” stand in stark contrast to the actual piece of radical filmmaking Valdez and Shank presented to the public. “The Sentence” offers an intersectional analysis of mass incarceration. Intersectionality argues for the need to study systems of oppressions as they overlap, not in isolation. The concept was articulated directly by critical race theorist Kimberle Crenshaw in 1989, but described in essence even earlier by anti-racist activists such as Ida B. Wells.

As articulated by Crenshaw, intersectional analysis is not an “oppression Olympics” through which we always find the most oppressed. While that is often the case, Shank’s story offers the central use of intersectional analysis as a critical tool in fighting mass incarceration. Intersectionality is meant to identify the oppression that has been overlooked.

The discernible variables of oppression analyzed in the “The Sentence” are race, gender, class and another frequently overlooked: childhood. Close attention is paid to the impact of incarceration on Shank’s three daughters, all ages five and younger at the beginning of the film. “The Sentence” reminds viewers that when one person serves time, the entire family serves time as well.

Toward the end of the film, Shank’s spouse Adam notes that she cannot get back what she has lost and that pain cannot be reversed. “The damage was done. … The kids felt the impact, I felt the impact, family did, friends, the community. When something like that happens, it doesn’t just affect that person,” states Adam Shank.

Far from an exception to the rule, the incarceration of women of color is central to mass incarceration. Since the 1970s, the women’s prison population has increased by more than 900 percent. Women of color have been the most impacted, with the number of Black women inmates rising more than 800 percent, while the number of white women inmates has increased by 200 percent. As with Shank and Alice Marie Johnson, this is the direct result of mandatory drug sentencing and other crimes.

In December 2016, Cindy Shank was granted clemency during the final days of Barack Obama’s presidency. Amidst Shank’s joy, she is visibly overtaken with sorrow and guilt when she realizes the odds she overcame and how many eligible inmates remain. In 2016 alone, more than 36,000 people met the guidelines for clemency, yet Shank was one of only 1,600 to be released.

Timely story

The emergence of Shank’s story is timely. The Obama administration and then Attorney General Eric Holder had instructed the Justice Department and federal attorneys to back away from mandatory minimum prosecutions, returning discretion over sentencing to the hands of judges. This is simply accomplished by removing the quantity of drugs from the federal charges levied against a defendant.

However, this compassionate measure never rose to the level of legislative reform — and as with all executive orders, they were rescinded upon the change in administration. In May 2017, Attorney General Jefferson Beauregard Sessions ordered a return to mandatory minimums by falsely claiming that Obama’s retreat had made the streets unsafer.

Independent analysts have connected the reinstatement of mandatory drug sentencing to the increased construction of for-profit federal detention centers. As seen in the case of the Boundary Park Four and More in San Diego, Calif. (tinyurl.com/ww-BP4-SD), activists believe that the government is attempting to fill those beds with people who use drugs and extremely low-level dealers — creating the image of uncontained crisis where there is none.

As noted, the story of Cindy Shank demands an intersectional understanding of mass incarceration. Shank’s story is a crucial story to be told, not because it is the most extreme or even the most common. The centrality of Shank’s story to intersectionality is that it is overlooked in the general heteropatriarchal analysis of mass incarceration. Shank’s story reminds us that when a family member serves time, everyone in that family serves time as well.

Conversely, just as Shank’s family fought endlessly to raise her story and gain her clemency, it is the collective action by all — across age, race and gender — that is needed to continuously fight for our freedom.