Revolt in education

Labor organizing has been explosive in the U.S. in 2018. Much of the militancy and organized rank-and-file opposition to ever-increasing austerity have come from education workers — public school teachers in West Virginia, Kentucky, Oklahoma and #RedForEd Colorado; school bus drivers in California, New York and Georgia; striking workers throughout the University of California system; graduate students on strike at Columbia University; and worker-student solidarity at the occupied New School cafeteria.

At the same time, teachers and students in Puerto Rico have been battling in the streets against U.S. economic colonization of public education on their island.

Such developments are particularly significant because labor organizing has been so consistently attacked through legislation and widespread demonization of unions. Organized labor has also been internally undermined due to divisions that have historically enabled racism, sexism, gender-baiting, scapegoating and pitting of groups against one another by the ruling class.

The massive wave of unrest and revolt in education does not come out of nowhere. Workers are responding to neoliberal policies and practices that stuff the pockets of the wealthy while attacking both workers and students with cutbacks in wages and programs for the common good. This is misery for the masses and opulence for the ruling elite.

Corporate media language implies cutbacks are a shared burden of increased austerity and privatization. But this is simply not true. Public education budgets remain constricted below 2008 levels. Teachers and other education workers are some of the lowest paid workers in the U.S. High tuition makes education an increasingly inaccessible realm for working-class college students. At the same time, military spending increases and tax cuts are put in place to benefit the wealthy.

The struggle of education workers arises from necessity — as it does for all working and oppressed people — in the face of stagnant wages and relentless attacks on benefits and the right to organize.

Meanwhile, students are not limiting themselves to their own immediate interests. In New York City, students at the New School occupied the university cafeteria in solidarity with workers threatened with job loss. Expressing unity and mutual recognition for human dignity, the students marched on May 1, chanting, “All of us or none of us.”

The students embodied the power that stems from awareness that they cannot fully liberate themselves while others are held in bondage. This is what Marx and Engels had in mind when they proclaimed that “the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.”

In 1968 a similar fervor gripped students in universities around the world. From the strike to demand an Ethnic Studies program at San Francisco State University to the upsurge of May-June in France, students were central to a revolutionary shift in consciousness. These and other student rebellions were grounded in both immediate conditions and the international student revolt against imperialism and oppression.

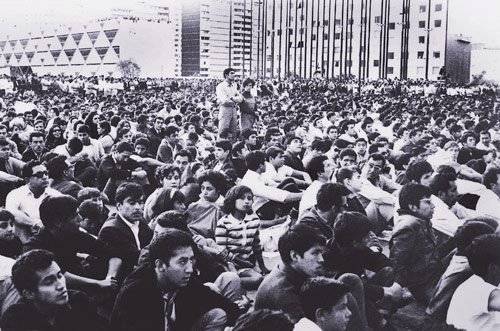

On Feb. 8, 1968, at South Carolina State University, a group of 200 Black students and community members protesting segregation were fired on by the state’s Highway Patrol. The state’s killing of three people and injuring of 27 at this historically Black college (HBCU) became known as the Orangeburg Massacre. On Oct. 2 in Mexico City, the repressive Díaz Ordaz regime carried out a horrendous assault on student demonstrations, the Tlatelolco Massacre, with conservative estimates of the death toll in the hundreds. Two years later came state murders of students at Jackson State University in Mississippi, also an HBCU, and Kent State University in Ohio.

These massacres highlight the ruling classes’ extreme fear of both organized revolt and the uncompromising resolve of students to participate in creating a better world.

The violently repressive nature of capitalism makes both unity and selfless commitment necessary.

Today’s struggles are taking place at some of the same crossroads as 50 years ago. The question remains whether education will continue to reinforce the relations of power or instead be transformed into a means of liberation.

The victory of the people, as was the case in 1968, requires that we overcome the divisions that facilitate exploitation.

The recent battles to defend public schools and universities are perhaps most inspiring because they bridge divisions between intellectual and physical labor, as well as between students and workers. The collective resolve of the education workers, students, parents and communities is a testament to the potential power of the working class.

The question remains whether workers in more industries and locations will follow their lead and help impel labor organizing to come back stronger and with a better understanding and commitment to solidarity forged through mutual struggle.