Textile workers built unions, led strikes and and fought racism

Eyes on North Carolina

Textile workers built unions, led major strikes and fought racism starting in the 1920s in the South’s largest industry. The heaviest concentration of textile mills was in North Carolina. Charlotte was the Southern industry’s center point since its inception during the post-Reconstruction era, with many factories ringing its perimeter, within a few hours drive.

Dick Reavis describes, in the Introduction to the Southern Worker online, “The Southern textile industry had boomed in response to government orders during World War I, but when peace came, orders and profits plummeted. Workers at more than a dozen mills went on strike in 1919-21, some of them spontaneously, some fanned by the AFL’s United Textile Workers. As many as 20,000 North Carolina [textile workers] walked out, including those at the Loray mill, [the largest textile plant in the region]. [But within] weeks, the mills were running again, having made no important concessions. The UTW largely abandoned the region, leaving both mill hands and their bosses embittered.”

Fred Beal, organizer for the National Textile Workers Union and the Communist Party, by March of 1929 realized that “North Carolina [is] key to the South; Gaston County [is] key to North Carolina, and the Loray Mill [is] the key to Gaston County.” Most of the 2,000 Loray workers lived in the company-owned, 450-unit village. Reavis writes, “In 1929, Loray’s white employees were laboring 55-66 hours per week for $12-$20, while their children worked 55-60 hours for as little as $5 per payday. The lowest-paid adult workers in the mill, a correspondent for the Baltimore Sun found, were African-American “scrubbers,” who earned $10.20 per week.” The plants were segregated.

On March 30, 1929, some 1,000 workers from the Loray Mill attended a meeting. Afterwards, five participants were fired. Workers agreed to strike unless the mill owners granted their demands to rehire those who’d been fired, end piecework, ensure a five-day week with a $20-dollar weekly wage, pay women and children equally, end speed-ups, and provide less costly, better housing. Moreover, they had to recognize the union.

1929: Strike wave in the Carolinas

The mill owners refused to accept the demands, forcing 2,000 white mill workers to strike. On April 3, Gov. Max Gardner, a mill owner, called in the National Guard, who arrested 10 striking workers the first day. When textile workers at nearby mills heard of the strikes, strikes soon occurred in Pineville, Forest City, Lexington and Bessemer City in North Carolina, and Spartanburg, Union, Woodruff, Anderson and Buffalo in South Carolina.

The union really didn’t have a strategy for including African-American workers, who faced racism every day. White workers were often concerned with economic issues while Black workers had to deal with physically defending themselves from frequent white supremacist attacks. Union organizing in the South required understanding its unique conditions.

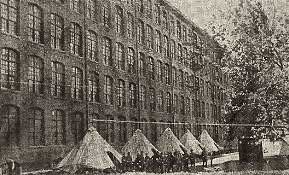

By the end of April, the Loray Mill owners began evicting striking workers from the company-owned housing. In May, the NTWU had constructed a tent city to house striking workers, along with a new union office building. Many workers returned to work, some returning to picket lines after payday only to be violently attacked by police officers. After run-ins between the police and workers, 100 masked men, mostly police, attempted to raid the union office on June 7, resulting in the death of Chief Aderholt, and the wounding of two officers and several workers. By night’s end, 75 workers had been arrested and charged with conspiracy and capital murder, including two communists. Sixteen went on trial.

On Sept. 15, 22 workers from the Bessemer City plant drove to Gastonia to support the ongoing protest. Company goons blocked and ambushed their truck and shot at them, killing Ella Mae Wiggins, a worker and fervent union supporter. A white worker, she supported struggling Black plant workers.

“For the next five months, the Communist Party and the International Labor Defense spent most of their resources to mount a defense in hearings, a mistrial, and finally, two Charlotte jury proceedings for the NTWU defendants whose indictments their lawyers had been unable to defeat,” states Reavis. Seven strikers and organizers who had fought off the June police attack were convicted. Denied an appeal, they forfeited bail and fled to the Soviet Union. Two returned, including Beal, and served prison time.

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt — following workers’ struggles across the country — signed the National Industrial Recovery Act, which promised better wages and working conditions. When mill owners reduced workers’ hours without raising their hourly wages in May of that year, the United Textile Workers, AFL, threatened a strike, pushed by Southern mill workers.

In September 1934, some 170,000 textile workers went on strike in the South,starting in Gastonia. The strike spread to the North, encompassed 1 million workers in the industry and was the largest strike in U.S. history at the time. It lasted 22 days. The bosses and their state governments mobilized 23,000 sheriff deputies, NationalGuard soldiers and private gunmen. Thirteen strikers were killed in the South, and two died in the North. Seven workers were murdered at the Chiquola Mill in Honea Path, S.C. The despair produced by this broken strike was manipulated by virulent racists, and the Ku Klux Klan grew in mill towns.

Black workers led struggle

against racism in the mills

Opening up the textile mills to Black workers was a long struggle. Textile barons didn’t quickly adhere to anti-discrimination laws won by the Civil Rights Movement. Housing in the Cannon Mills’ company town of Kannapolis, N.C., was still segregated in 1969. Jim Crow bathrooms were the norm in the Greensboro plants of the Cone Mills until 1973.

African-American workers led the fight against racist discrimination in the textile industry. In September 1965, Shirley Lea, with other African-American women, applied for work at the Cone Mills plant in Hillsborough, N.C. Denied jobs, they filed a groundbreaking lawsuit, Lea v. Cone Mills, under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

In October 1969, Julius Adams — who was a leader of the 1963 civil rights protests in Danville, Va. — and 24 other Black workers sued Dan River Mills for biased hiring and promotion policies and segregation in the plants. Betsy Ann Broadnax took Burlington Industries, the biggest textile company of them all, to court.

Despite these actions, in 1969, President Richard Nixon refused to enforce anti-discrimination provisions in military contracts held by Burlington Industries, J.P. Stevens and Dan River Mills.

Yet the struggle continued. In 1970, Lucy Sledge sued J.P. Stevens, the second-biggest textile company, for racial discrimination in 11 plants in Roanoke Rapids, N.C. She was joined by 3,000 textile workers. Just a year before, the company had hired only 18 percent of African-American men and 4.5 percent of the Black women who sought work there, as compared to employing nearly 50 percent of white male and 25 percent of white female job applicants.

Black workers persevered and made inroads into the textile industry. In 1976, nearly 33 percent of South Carolina textile workers were African American, up from 5 percent 12 years earlier. By 1980, African-American women formed 21 percent of the industry’s workforce countrywide, up from 12.4 percent in 1972.

The largest union organizing drive of the 1970s was against J.P. Stevens. African Americans comprised 23 percent of its workforce in 1974. The textile company’s big Roanoke Rapids plant — where African-American workers made up 40 percent of the employees — was the heart of the union campaign. They voted in the Textile Workers Union that year.

Spurred on by these workers, the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union, formed in 1976, pushed on. Aided by a national boycott, the union forced J.P. Stevens to sign a contract in 1980.

On Sept. 3, the Southern Workers Assembly, will be held from 1 – 5 p.m., at Wedgewood Baptist Church, 4800 Wedgewood Drive, Charlotte, N.Car. See SouthernWorker.org for information.

Stephen Millies contributed to this article.