A review of Africa 2016: Socialism is answer to solve oil crisis

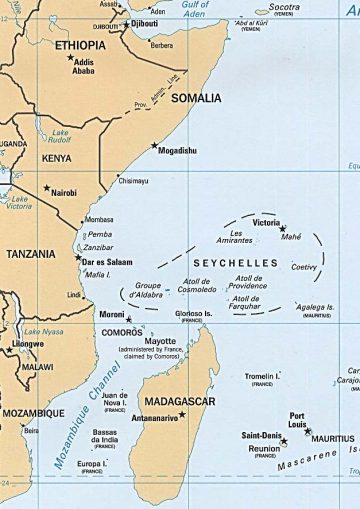

Substantial finds of oil and natural gas resources have been under development along the Indian Ocean coast in East Africa in recent years.

Substantial finds of oil and natural gas resources have been under development along the Indian Ocean coast in East Africa in recent years.

British exploration corporation Tullow Oil and its Canadian partner, Africa Oil, have “discovered” over 600 million barrels of oil in Kenya. Since 2012, at least eight exploitable and viable oil sources have been recorded.

In neighboring Uganda, 6.5 billion barrels of oil deposits have been found since 2008. Tanzania, another East African Community member, harbors about 50.5 trillion cubic feet of natural gas resources.

The southern African state of Mozambique — not an EAC member — has also discovered natural gas, with reserves estimated at around 200 billion cubic feet. The combined natural gas resources in Tanzania and Mozambique are among the most lucrative in the world.

Yet today’s overproduction of oil and natural gas resources has driven down prices on the international market. As a result, states which rely on these strategic energy sources have fallen into economic decline. Although some countries in Africa and other regions are described as being in recession, considering the precipitous drop in currency values and debt accumulation, “depression” may be a more accurate description.

In Mozambique, financial speculation centered on these natural resource projects has drawn the attention of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Allegations of impropriety involving financial institutions are providing an opening for further interference in the country’s internal affairs. Mozambique won its independence through a popular revolutionary armed struggle led by the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) against NATO member Portugal in 1975.

The Wall Street Journal reported on Dec. 28: “The [SEC] is investigating the sale of $850 million in bonds issued by Mozambique. … The move inserts the U.S. into a widening global investigation of Mozambique’s debt deals, which involved undisclosed loans and military purchases facilitated by [international] banks.”

These developments are taking place amid a recrudescence in the counterrevolutionary war waged by the so-called Mozambique National Resistance (RENAMO). This organization grew out of the Portuguese intelligence agency’s counterinsurgency operations aimed at undermining the national liberation struggle which was committed to socialist development in Mozambique. RENAMO was funded and trained by the then settler-colonial regime of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). After Ian Smith’s Rhodesia fell in 1980, South Africa’s apartheid regime took over RENAMO’s operations. The group sought to destroy Mozambique’s newly liberated state led by the late President Samora Machel.

FRELIMO leader Machel was killed in a plane crash in 1986. Reports suggested the plane was brought down during South African military operations against the encroaching liberation movement of the African National Congress.

RENAMO claims it is fighting for a greater say in Mozambique’s political structures, yet it has operated as a political party since a ceasefire was signed with the FRELIMO government in the early 1990s. The renewed hostilities raise concerns about the future economic and social well-being of the country, a leading member of the regional Southern African Development Community.

Angola: Which way out of the oil crisis?

The Republic of Angola, another former Portuguese colony, won its independence through armed struggle from 1961 to 1975. Its independence was threatened by interventions by the U.S. and the apartheid regime’s South African Defense Forces from 1975 to 1988. Hundreds of thousands of Cuban internationalist volunteers secured the country’s liberation by 1989. This led to freedom for Namibia, a former German colony, and later the downfall of the settler-colonial regime in South Africa.

Angola has been impacted by the petroleum crisis as its revenue largely depends on oil exports. The country has been the first- or second-largest oil producer in Africa. The ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola remains the dominant political force there.

A Jan. 2 Wall Street Journal article emphasizes the impact of the drop in oil prices on Angola. During this decade’s early years, economic growth was so vibrant that the government even loaned money to its former colonial master, staving off a potential collapse in Portugal. The Journal said gated communities built for a middle class “that never materialized” are mostly empty, and the foreign elite left when the oil-price boom went bust in 2014. Stores “struggle to stock their shelves, as a free-falling local currency and dollar shortages batter imports.”

This report discusses the Angolan government’s travails in seeking a way out of this crisis: “The International Monetary Fund expects that Angola’s economy will have zero growth in 2016 … a disaster for a country whose population of 26 million is growing by 3.2% annually. [The IMF estimates] government debt has jumped to 78% of gross domestic product, from just 41% when oil prices plummeted in 2014.”

Analysts warn about its ability to repay its debts. Since the government abandoned bailout negotiations with the IMF in July, “the central bank has used 18% of its foreign-currency reserves to keep some imports flowing into the country.” Investors warn reserves will run out “if spending continues at this pace.”

Pan-Africanism, socialism and the global crisis

Although there appeared to be a renaissance in African political economy during a supposed “recovery” from the Great Recession in the imperialist states of Western Europe and North America from 2007 to 2010, this growth in regional business activity is proving to be unsustainable. From Egypt and Nigeria to South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo, the postcolonial nation-states are at a crossroads.

The prospects for foreign direct investment in natural resource development markets have reached a breaking point due to overproduction of oil and gas. The U.S. has pursued a concerted strategy to curtail imports of oil and natural gas — and to utilize domestic production through hydraulic fracking, shale technology and offshore drilling. The ostensible “recovery” in the U.S. has been mostly untenable since it is largely based on stock market speculation, tax cuts for the super-rich and the normalization of low-wage employment.

There is a dire need in Africa for continental integration based on socialist planning. The merging of economic projects and political unity provides the only real solution for the perpetual ebbs and flows of global capitalist economic viability.

With the incoming administration of President-elect Donald Trump, the Pentagon and intelligence apparatus are mounting pressure to continue the renewed Cold War against the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China. Such a policy will have profoundly negative consequences for the African continent.

Fostering socialist development in Africa would require the mass mobilization and organization of the youth, workers and farmers. It would necessitate the disruption of dependence on foreign direct investment as the primary mode of economic growth. The emphasis must be placed on political education with the objective of creating a unified continent under socialist relations of production.

Moreover, the collaboration between the imperialist states and the U.S. Africa Command should be halted. These military joint ventures have further destabilized the continent in Mali, Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria and elsewhere.

A continental military force should be independent of the imperialist states. As Dr. Kwame Nkrumah said over 50 years ago, the creation of an All-African High Command would serve as a defense against neocolonialist intervention — and not a gateway for its proliferation.

2017 will be an important year for the African continent. It is up to youth, workers, popular movements and governmental leaders to decide on the correct path to revolutionary liberation and unification.