Russians go to polls facing looming U.S.-NATO threats

On Sept. 18, citizens of the Russian Federation will elect 450 members of the State Duma, the lower house of the Federal Assembly. In addition, 39 regions will choose legislative assemblies, seven regions will elect governors, and municipal elections will be held in 5,000 cities and towns.

On Sept. 18, citizens of the Russian Federation will elect 450 members of the State Duma, the lower house of the Federal Assembly. In addition, 39 regions will choose legislative assemblies, seven regions will elect governors, and municipal elections will be held in 5,000 cities and towns.

Crimea will participate in a national election for the first time since seceding from Ukraine and reuniting with Russia in 2014.

With some fluctuations, the current political makeup of the Duma is expected to continue, with President Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party in first place, followed by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation led by Gennady Zyuganov, the right-wing nationalist Liberal Democratic Party and the moderate Fair Russia party.

Fourteen other parties automatically qualified to run candidates. Eight more gathered the 200,000 signatures needed to gain a place on the ballot. But none of these 22 parties are expected to break the 5 percent threshold needed to receive seats in the Duma.

Bloomberg News, echoing many Western media outlets, labelled this “the most boring election of 2016.” Certainly no one expects the kind of protests that hit Moscow and other big cities after the last Duma election in 2011.

However, that doesn’t mean the election is unimportant.

For one thing, polling in Russia is an enormous undertaking, involving 111 million eligible voters (including 1.9 million living abroad), covering a territory of 6.6 million square miles. These voters will choose among 103,000 registered candidates in the various contests, according to Central Election Commission Chair Ella Pamfilova.

Since Pamfilova’s appointment, the Russian government has attempted to increase the transparency of the election process. The rules for Duma elections have changed significantly since 2011. Then, all candidates were selected from party lists.

This time, two forms of voting will take place side by side. Half of Duma members will be chosen by the same method of proportional representation for political parties that pass the 5 percent threshold. But the other 225 will be elected in local, single-member districts, with the top vote-getter winning the seat. This change potentially opens up much broader participation by individuals and representatives of other parties and movements.

Finally, every person who goes to the polls Sunday — or chooses not to — will be acutely aware of the dramatic change in Russia’s international relations since 2011: the Western-backed coup and civil war in neighboring Ukraine; sanctions imposed on Russia by the U.S. and the European Union over its reunion with Crimea; the war against the Islamic State group in Syria; and the provocative military posturing by Washington and NATO in eastern Europe against the alleged “Russian threat.”

When the U.S. intervenes in elections

Democratic Party officials have charged — and this is repeated ad nauseam by the U.S. media — that Russia’s government is trying to influence or even “steal” the U.S. presidential election on behalf of Donald Trump.

Yet, for all the hours of talking heads and columns of ink devoted to these (completely unsubstantiated) claims, not one has mentioned how the U.S. routinely interferes in other countries’ elections — including Russia’s.

The role of foreign-sponsored nongovernmental organizations has become a matter of great concern for Russia since 2011 — especially after the part these groups played in the overthrow of Ukraine’s elected government in 2014. NGOs that receive major funding from foreign sources are now required to register as “foreign agents” with the Russian government.

In the past year, U.S.-based NGOs — from George Soros’ Open Society Institute to the International Republican Institute — have been added to Russia’s list of “undesirable organizations” banned or placed under close scrutiny.

This is one reason that pro-Western political parties are in disarray and have little hope of advancing in the Sept. 18 elections.

Another is the resurgence of anti-fascist sentiment in Russia since the coup in Ukraine, the subsequent reunion with Crimea and the war waged by Kiev authorities and neo-Nazi groups against the breakaway Donbass republics of Donetsk and Lugansk.

On Sept. 5, the Russian Justice Ministry announced that the Levada Center, an NGO calling itself Russia’s main independent polling service, had been ordered to register as a foreign agent.

An investigation revealed that Levada — long known for its affinity to pro-Western, neoliberal political parties — receives much of its funding from Western sources, including a grant from the University of Wisconsin at Madison curated by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Other sources of funding include George Washington University, Columbia University, the U.S.-based Gallup poll company, and businesses in Britain, Germany, Switzerland and Norway. (TASS, Sept. 6)

How the left participates in the elections

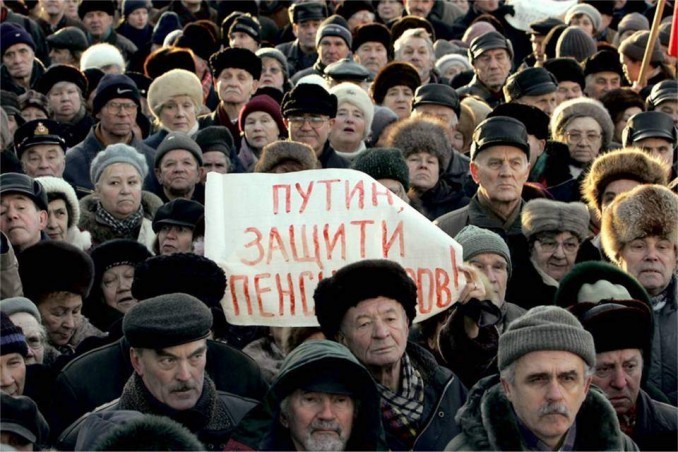

The Soviet Union broke up 25 years ago. Polls have shown that the majority of Russians and residents of other former Soviet republics regret its breakup. Many wish they could return to a socialist system that guaranteed jobs, education, health care and other essential needs.

Despite the economic downturn that has hit Russia and other major oil producing countries, President Putin’s popularity remains high. He is seen as standing up to the coup-makers in Ukraine by accepting the Crimean referendum to reunite with Russia in the face of Western threats and sanctions.

What about leftist parties that oppose Western imperialist influence but also seek to organize the working class against capitalist rule in Russia?

Some groups have called for a boycott of the elections. But others, while pointing out that elections under the current system cannot bring about socialism, are campaigning to gain a wider audience for their program.

In Moscow, for example, the United Communist Party is running candidates in three single-member districts. Party leader Vladimir Lakeev succeeded in getting the 15,000 signatures required to win a slot on the ballot — one of only two Moscow candidates to do so. His comrades Darya Mitina and Vladimir Strukov are running on the ticket of the Communists of Russia party, a group with national ballot status.

In St. Petersburg and Dagestan, the Russian United Labor Front is also running candidates in single-member district races. These candidates all receive local television airtime for campaign advertisements and are able to participate in televised debates, giving them the opportunity to reach workers who might not otherwise hear their message.

The candidates have taken to the streets with sound cars, rallies and information booths. Lakeev was even briefly arrested on Aug. 31 after he draped a banner from a landmark arch reminding Muscovites of the approaching centenary of the Russian Revolution in 2017.

“We raise issues of immediate concern to Moscow residents, including reform of the health care system, environmental problems, land ownership and property relations, inflation, social inequality and more,” Lakeev explained.

“We communists have never entertained illusions about the role of elections in capitalist society, where everything is decided by money. For us, this is just one of the tools to appeal to the people. Using the elections as an opportunity to appeal to the public, we put acute social questions on the agenda, and explain the need for an organized struggle for their rights, which no visit to the polling station can replace.” (Comstol.info, Sept. 5)

This article was published by TeleSur on Sept. 18.