50th anniversary of the Black Power slogan and its significance

On June 16, 1966, the newly elected chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Stokely Carmichael, later known as Kwame Ture, was arrested and taken to jail in Greenwood, Miss., for refusing to obey a police order. Law enforcement officers forbid marchers from erecting tents at an elementary school where activists planned to stay overnight during their “March against Fear” from Memphis, Tenn., to the state Capitol in Jackson, Miss.

On June 16, 1966, the newly elected chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Stokely Carmichael, later known as Kwame Ture, was arrested and taken to jail in Greenwood, Miss., for refusing to obey a police order. Law enforcement officers forbid marchers from erecting tents at an elementary school where activists planned to stay overnight during their “March against Fear” from Memphis, Tenn., to the state Capitol in Jackson, Miss.

When marchers arrived in Greenwood that evening and tried to erect a temporary camp at the segregated Stone Street Elementary School, Carmichael was arrested for “trespassing on public property.” He was taken into custody for several hours and later rejoined the marchers at a local park, where they established a camp and held an evening rally.

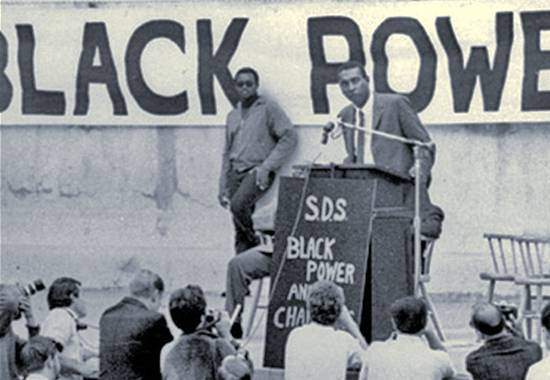

There, Carmichael famously announced from the podium: “We been saying ‘freedom’ for six years. What we are going to start saying now is ‘Black Power!’”

Background of ‘March Against Fear’

This historic march started off on June 5 as a solo journey of James Meredith, the first African-American student to enter and graduate from the University of Mississippi, who planned to walk 220 miles from Memphis to Jackson. On the second day of his journey, 20 miles into Mississippi, James Aubrey Norvell, a white racist, shot Meredith in the head with a shotgun. Wounded and bleeding, Meredith was rushed to a hospital. For another two weeks, while hospitalized, he could not continue marching.

Leaders of SNCC; the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, headed by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; and Floyd McKissick of the Congress on Racial Equality pledged to continue the march at a press briefing the day after Meredith was wounded.

As the march neared Jackson, growing in size, Meredith was able to rejoin it, and on June 26, an assemblage of 15,000 people reached Mississippi’s Capitol building in this historic demonstration.

From ‘Freedom NOW’ to ‘Black Power’

Willie Ricks, a SNCC field organizer, had informed Carmichael that the masses in the Mississippi Delta region were ready for the new, more militant slogan and the program, which advanced self-defense, self-determination and opposition to the Vietnam War. Carmichael, recently elected SNCC chairperson, had a clear objective of moving the organization in a more radical, nationalist political direction.

Ricks used the new slogan as he traveled ahead of the “March against Fear,” building support for it and mobilizing SNCC supporters throughout the region. SNCC had worked in Mississippi since 1961. In 1964, the organization spearheaded the Mississippi Summer Project, which brought hundreds of youth to the state to work on voter registration and to build the independent Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

After the Selma-to-Montgomery march in early 1965, Carmichael, on SNCC’s behalf, went to majority African-American Lowndes County, Ala., to initiate another independent party. By late 1965, in cooperation with local activists, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) had been established, using the black panther as its symbol.

Although Lowndes County was majority African American, almost no Blacks were allowed to register and vote. The Democratic Party of Alabama was a white supremacist organization, even stating that on its emblem.

As a result of the national attention brought to Lowndes County, Carmichael, along with his SNCC comrades, was able to take control of the organization. The “March Against Fear,” which received broad media coverage on all the major networks, catapulted Carmichael into a global spotlight.

Carmichael was initially resistant to raising the slogan, but after his unjust arrest, he asserted in Greenwood, ”We want Black Power!” The enthusiastic response to the slogan ushered in a new era of the African-American liberation struggle, which impacted political discourse for at least another decade.

Even prior to the “March Against Fear,” the work of SNCC and the LCFO had prompted other activists to form Black Panther organizations in several regions of the country, including Cleveland and Detroit — where rebellions had taken place in the Hough section and later on Kercheval Street on the east side. Detroit’s August 1966 mini-rebellion was a precursor to the largest urban uprising, which began on 12th Street on July 23, 1967.

Many African-American youth and their counterparts in the Latino/a, Native American, Asian and other communities formed organizations similar to SNCC and the Black Panther Party (BPP). Backed by their parents, university and high school students demanded reforms in educational curriculums as well as community control of the police.

Black Power’s significance today

Five decades later, many gains made through the Civil Rights and Black Power movements have been reversed by the courts, the federal government and corporate forces. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 has been eviscerated, the law stripped of its enforcement provisions.

Cities in Michigan with majority African-American populations were put under emergency management — through which large-scale theft of public resources, educational services and bourgeois democratic rights have occurred — with the support of President Barack Obama’s Democratic administration.

African Americans and other oppressed groups are brutalized and killed by law enforcement agents and vigilantes with regularity. Last year, some 1,134 people were killed by U.S. police. (Guardian, Dec. 31) In most cases, these crimes have gone unpunished, as judges, prosecutors, the U.S. Justice Department and the corporate media claim there is insufficient evidence to try and convict the perpetrators.

Jobless rates among African Americans remain twice as high as for whites. Poverty rates among the oppressed far exceed those of the broader majority white population.

U.S. foreign policy continues on its imperialist path with wars of occupation and regime change raging throughout the Middle East, Africa, Asia and Latin America. The Pentagon budget is larger than the combined military expenditures of the next seven (or eight) highest spending nations. (Huffington Post, Feb. 11) The Obama administration is launching a renewed $1 trillion nuclear weapons program amid growing poverty and desolation in U.S. cities, suburbs and rural areas.

Lessons of the Black Power Movement

Can any lessons be learned for the contemporary period in light of the presidential elections being held amid a renewed struggle against racist violence, economic exploitation and poverty? Is there a direct relationship between the Black Lives Matter movement and the revolutionary upsurge of 50 years ago?

The lack of historical memory has been a major impediment in the present situation. Even though a president of African descent was elected twice to the White House, there have been no fundamental changes in the power structure and economic relations of production in U.S. capitalist society.

Consequently, a revolutionary movement encompassing various organizational forms is necessary to address the current crisis. The limitations of spontaneous demonstrations and rebellions have been illustrated since 2013 when public sentiment against the racist killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland and other oppressed peoples sparked mass anger and protests.

Absent from today’s political landscape are organizations, such as SNCC and the BPP, which place organizers on the ground in communities and on campuses to mobilize and agitate for revolutionary change. This is the major challenge of this period. It can only be addressed by the newer generation drawing upon the best of the political traditions among oppressed peoples and the entire working class.