Cuba eliminates mother-to-child transmission of HIV

Cuba became the first country certified by the World Health Organization as having eliminated mother-to-child transmission of HIV and syphilis.

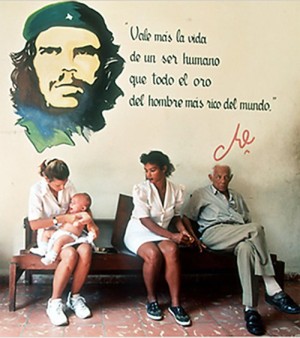

‘A human life is worth more than all the gold of the richest man on

earth.’ Che Guevara’s comment fits Cuba’s socialist medical system.

“Cuba’s success demonstrates that universal access and universal health coverage … are the key to success, even against challenges as daunting as HIV,” said Dr. Carissa F. Etienne, director of the Pan American Health Organization, WHO’s Regional Office for the Americas, in a June 30 news release. “This is a celebration for Cuba and a celebration for children and families everywhere.”

Globally, about 1.4 million women living with HIV become pregnant each year. Without treatment, up to 45 percent of their babies will become infected. Medication for mother and newborn can bring that down to about 1 percent.

This writer — who provided prenatal care to HIV-positive women and was involved in research to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV during the early 1990s in the United States — was not surprised to see Cuba’s achievement. The Cuban medical system has an excellent record of providing the best care available to everyone by focusing on the population’s needs, with no focus on profits.

AIDS was first identified in 84 Cubans who were among 300,000 military personnel returning from Africa in the 1980s, where they played a crucial role in defeating apartheid forces in Angola. A nationwide screening program began in 1986, when Cuban scientists developed their own HIV test, despite the economic and information blockade that hinders scientific exchange. (American Journal of Public Health, May 1991) Eighty percent of the sexually active population, about 3.5 million people, were screened; 268 HIV-positive individuals were identified.

Testing and tracing of sexual contacts followed standard public health procedures, but more thoroughly than in other countries, according to the Health and Human Rights Journal, September 2009. One of those first measures was quarantine (1986-1989), later replaced by outpatient treatment, education and patient peer groups. Since 1988, HIV education has also been part of Cuba’s school curriculum starting in the fifth grade.

The quarantine period was not directed at gay and bisexual men — who were then only 21 percent of those who tested positive. Women formed the same percentage of the infected. Currently, men who have sex with men are a majority of HIV-positive people in Cuba.

After the development in 1996 of highly active anti-retroviral treatment (HAART), Cuba bought ART drugs for all children with AIDS and their mothers, at a cost of $14,000 per person per year. The Cuban medical organizations and government prioritized this expense despite Cuba’s deep economic crisis in the mid-1990s after the collapse of the USSR and as the U.S. blockade deepened under President Bill Clinton. Since 1998, Cuba has been producing its own low-cost generic HIV medications.

In addition to this latest achievement in mother-child health, Cuba has the lowest infant mortality rate in the Americas. It also leads the world in numbers of health care workers sent to respond to the Ebola epidemic.

“After the devastating [2010] earthquake in impoverished Haiti, Cuba sent the largest medical contingent and cared for 40 percent of the victims. Following the Kashmir earthquake of 2005, Cuba sent 2,400 medical workers to Pakistan and treated more than 70 percent of those affected.” (Guardian, Dec. 3, 2014)

While the U.S. and Europe suck health care workers out of poor countries, Cuba established the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) and has graduated more than 20,000 doctors from over 123 countries since 1998.

Cuban immunologists have made several vaccination breakthroughs — for meningitis B, hepatitis B and lung cancer. (Wired Magazine, May 11, 2015) Cuba also launched a vaccination campaign against malaria, which affects mainly children, in 15 West African countries and restored the sight of 3.5 million people in Latin America. (Huffington Post Aug. 8, 2014)