Looking back at the anti-war movement 40 years after Vietnam’s victory

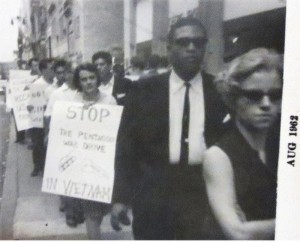

In August 1962, when Youth Against War & Fascism held the first protest in the U.S. against the Vietnam War, the reaction of passers-by on 42nd Street in New York City was puzzlement. They didn’t know where Vietnam was; some didn’t even know it was a country. U.S. forces sent to South Vietnam at that time were called “advisers.” Yet the resistance of the Vietnamese to becoming a U.S. neocolony and the struggle here against that dirty war were to define a whole generation. That generation is a lot older now.

The U.S. escalation came in 1964, with the fraudulent Bay of Tonkin resolution passed by Congress that gave President Lyndon Johnson authority to send millions of young draftees to Vietnam. The war finally ended on April 30, 1975, with the ignominious routing of the last U.S. Embassy personnel from Saigon, who clung to helicopter skids as they made their escape.

The 40th anniversary of that decisive defeat of the most powerful military machine on earth has now evoked many retrospective accounts in the U.S. media.

This writer, who was on that first U.S. protest and hundreds of others as the war and the movement against it grew, picked up a copy of the April/May AARP magazine the other day and found a photo of a YAWF demonstration in 1965 at the White House carrying signs saying “Bring the GIs home now.” It brought back memories.

Many former soldiers still carry the physical scars of ferocious combat. Other tormented souls suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder after being programmed to believe it was patriotic to participate in atrocities. By contrast, those in the anti-war movement can look back on their youthful rebellion against the capitalist state and its propaganda machine with pride and satisfaction.

One of the biggest lies about the movement was that it was against the U.S. soldiers. Hell, most of them welcomed the slogan “Bring the GIs home now.” That’s what they wanted — just to come home, in one piece. Our quarrel was with the high-ranking officers, the ones who go through the revolving door to lucrative executive positions in the “defense” industry after they retire. And of course we demonstrated against the political architects of the war, in the Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon administrations, who saw it as key to the worldwide effort of U.S. imperialist rulers to defeat communism.

What they meant by “defeating communism” was stopping the effort of workers and farmers around the world to take charge of society and distribute the wealth only they create to its producers. The bosses wanted that wealth for themselves.

It was these bosses in and out of uniform, not the GIs, who understood which class had created that beastly war and followed its orders. YAWF, on the other hand, helped the rank-and-file soldiers build the American Servicemen’s Union to assert their rights — such as refusing an illegal order like the order to fight in Vietnam — as well as to reject racism, sexism, saluting and “sir”-ing of officers, and all the other tricks of the military brass meant to divide the soldiers and keep them under control.

Black and Brown GIs in particular organized against the war. Many recognized in the vile language their commanders used to degrade the Vietnamese people the same racism and arrogance they suffered back at home. Young people inspired by the Civil Rights movement became increasingly anti-war, and soon Black leaders like Stokely Carmichael, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X campaigned against it.

The killing of four students at Kent State University by the National Guard on May 4, 1970, galvanized the movement into more militant actions. What has long been overlooked, however, is that just 11 days later, during a protest against that massacre, police in Jackson, Miss., shot and killed two Black students at Jackson State University and wounded many others.

YAWF: ‘Stop the war on Black America’

The umbrella anti-war movement at that time was not as bold or politically advanced as the youth in the streets. YAWF adopted the slogan, “Stop the war on Black America,” that it brought to all the mass demonstrations against the Vietnam war. At one annual peace rally in Central Park, more conservative organizers of the umbrella movement actually dissed anti-war forces in Harlem by inviting Mayor John Lindsay to speak right after he had signed a stop-and-frisk order giving New York police an open door to arrest thousands of Black youth.

YAWF took scores of arrests that day marching against that order — while Lindsay said nothing about Vietnam in his brief remarks to the large rally and immediately went to speak at a small pro-war event elsewhere in the park.

Thus the struggle against the war also had to be a struggle against conservatism in the movement itself, especially regarding national oppression and racism.

YAWF was the youth organization of Workers World Party. Many other left parties sprung up in the 1960s, but few have endured today. The ideology that has sustained WWP is based on a Marxist, class understanding of contemporary society.

The war drive is rooted in capitalism itself, as the Russian revolutionary leader V.I. Lenin explained so thoroughly in his 1916 work “Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism.” The anti-war struggle must be part of the fight against all the evils of capitalism — low wages, union-busting, racism, sexism, anti-lesbian/gay/bi/trans/queer bigotry, mass incarceration, police terror and more.

Imperialism is the last stage of capitalism — and this system has gotta go.