Disability rights: A rich theatre of the class struggle

The 1970s saw the development of a very active ex-patient and psychiatric survivor movement. In 1974, the Network Against Psychiatric Assault (NAPA) was among many organizations founded by people who had experienced psychiatric diagnoses. Also, a sister organization to NAPA was established in Boston, the Mental Patients Liberation Front.

NAPA raised the rights of people in the mental health service system as a human rights issue and exposed and opposed abuses of psychiatric force, including drugging, electric shock treatment and psychiatric imprisonment. Other issues raised were the use of patients as forced labor and the uninvestigated death of patients in psychiatric facilities.

NAPA organized pickets of the pharmaceutical companies and the American Psychiatric Association. Their militant picket lines and sit-ins were instrumental in getting abusive institutions closed and in getting laws passed limiting involuntary shock treatment in California. They formed the roots of today’s peer support movement.

Activists in power chairs circled buses

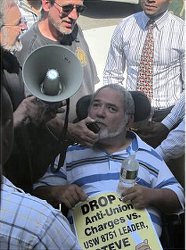

The struggle for accessible public transportation was already ongoing when ADAPT, a national organization, was started in 1983. Originally an acronym for Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, this militant group practiced “nonviolent direct action” to win civil rights for people with disabilities. Some 40 to 50 people in power chairs surrounded inaccessible buses.

ADAPT also set up picket lines and held direct actions against the American Public Transit Association, which was made up of industry leaders who design rolling stock [transit vehicles] — like buses, subways and trains. This struggle won significant concessions, including the rewriting of some access regulations.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, ADAPT changed its name to Americans Disabled for Attendant Programs Today, and refocused their emphasis to getting personal assistance services that people with disabilities need to remain at home or to leave institutions. These services are neither medical nor medicalized, yet nursing homes and other facilities make profits by providing them to people who want to be at home. An ongoing struggle is to obtain adequate hours from personal assistants and adequate pay and benefits for them. These workers help with daily living tasks, like getting up in the morning, showering and getting ready for bed at night.

ACT UP won lower drug prices

The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), which was led by people with HIV and AIDS, was one of the most significant movements of the 1980s. Formed in 1987 at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in New York City, the organization described itself as “an international direct action advocacy group working to impact the lives of people with AIDS and the AIDS pandemic to bring about legislation, medical research and treatment and policies to ultimately bring an end to the disease by mitigating loss of health and lives.” (actupny.org)

ACT UP’s creative direct actions targeted Wall Street, the Stock Exchange, federal government offices, pharmaceutical companies and medical associations. The group demanded a coordinated national policy to fight the disease, greater access to experimental AIDS drugs and affordable medication. It also exposed and fought the misinformation and frenzy concerning AIDS, its transmission and the social stigma associated with the illness. ACT UP led this struggle.

The first HIV/AIDS treatment medications — AZT and anti-retroviral drugs — cost an astronomical $10,000 a year; no insurance companies would cover them. ACT UP waged a successful direct action campaign aimed at Burroughs Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline), AZT’s manufacturer, demanding that the company stop its profit-gouging and lower the price — to keep people alive.

“We demand solidarity, not charity”

During the 1990s, there was much organizing to confront the nauseating media portrayals of people with disabilities. There had been mobilizing against those perceptions a long time before then, but during that decade, this issue got more visibility.

One focus was the Jerry Lewis Muscular Dystrophy Telethon, held every Labor Day to raise money for the Muscular Dystrophy Association. The telethon highlighted children with leg braces and crutches, called “Jerry’s Kids.”

In 1991, people calling themselves “Jerry’s Orphans” organized picket lines in Chicago outside media outlets that showed the telethons. They exposed them as media spectacles, which presented the bourgeois view of charity, instead of solidarity. The class view of charity means those with more financial means toss a few pennies or crumbs to people far below them, ones whom they deem as “worthy.” If they don’t see them as “worthy,” they don’t toss any crumbs at them.

These telethons were targeted because they presented people with disabilities as needing pity and charity — rather than accessible public transportation, housing, employment opportunities, and other economic and civil rights.

Fighting the right wing to pass the ADA

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was enacted by Congress and signed into law in 1990. It is a civil rights law that prohibits, under certain circumstances, discrimination based on disability. The ADA defines disability as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” (ada.gov, section 12102)

The act gives similar protections against discrimination against people with disabilities as did the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made discrimination based on race, religion, sex and national origin illegal.

The right wing attacked this law even before it was passed. Outright bigots, such as North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms, tried to stop the momentum for passage of the ADA. They whipped up a frenzy and fear around people with AIDS, who are protected by the ADA — some might be working in food service. So Helms and others tried to add to the ADA draconian restrictions on food service workers that were unscientific about sanitation or what illnesses could be contracted from food handlers. But activists organized to fight back — and stopped this.

The ADA represented significant gains. But it is important to remember that, like any other piece of legislation, it reflects the strength of the class struggle at that time. The right wing was able to whittle away at some of the ADA’s important provisions, and gutted much of Title 1 of the law, which prohibited discrimination in employment.

The ADA was won by fierce and protracted struggle by people with disabilities and their supporters. As with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the struggle now is to protect its gains, get it fully implemented and expand its scope.