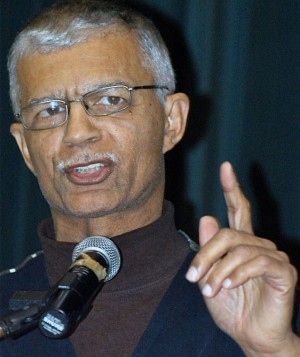

Honor Chokwe Lumumba

Build a people’s assembly

Jackson, Miss. — On March 8, hundreds of people, especially from the South and particularly Jackson, Miss., came to mourn and reflect on the life of Mayor Chokwe Lumumba, who died suddenly on Feb. 25 at the age of 66. Starting with a March 5 tribute at the historically Black college, Jackson State University, Mayor Lumumba’s life was memorialized for several days, ending with the masses lining the streets for his burial motorcade.

People gathered for the “Home Going Ceremony” in the main room in the Jackson Convention Complex, with hundreds more in an overflow area. They were regaled for hours with stories of a young Chokwe, before he took the name honoring an African people who resisted slavery, the Chokwe of Central Africa, together with the name of the great anti-imperialist Patrice Lumumba, the first elected Prime Minister of Congo assassinated at the behest of the CIA in 1961. The ceremony was filled with music and dance from African traditional to contemporary.

Besides his son, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, and daughter, Rukia Lumumba, those on the program included Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of slain NAACP leader, Medgar Evers; Civil Rights leader Hollis Watkins; Congressperson Bennie Thompson; interim Jackson Mayor Charles Tillman; former Mississippi Gov. William Winter; and singer Cassandra Wilson. Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan sent a condolences statement.

It was only eight months ago that Chokwe Lumumba was elected mayor of Jackson, the seat of the state Capitol, winning with 87 percent of the voting electorate. The Jackson-Kush Plan, the platform he ran on, is as much or more responsible for Mayor Lumumba’s victory than his demeanor and political history.

The model of participatory democracy and building People’s Assemblies is central to the Jackson-Kush Plan. Viewed as part of the process to consolidate political power in the hands of the Black masses in the city, the plan is connected to the struggle for self-determination. Mayor Lumumba saw this plan as a long-term process, with the Jackson People’s Assembly instrumental to its success, which began with his election to the City Council and then as mayor.

Building people’s power is a long-term prospect with the goal to educate and empower the masses through action and struggle. This is integral, especially in a city and a region that is prone to reaction and where the level of impoverishment, education, infrastructure and repression resembles those of an oppressed developing nation.

Why Jackson needs people’s power

Jackson is in the poorest U.S. state, economically. There are more poor people, especially Black people, on Medicaid in Mississippi than in any other state. Jackson is an 80 percent Black city, with high poverty rates and unemployment and a crumbling infrastructure, evident from its sewage problems. It has been neglected and divested like majority Black cities such as Detroit.

The structural improvements needed to fix the infrastructure would cost hundreds of millions of dollars, possibly billions. To make up for the years of neglect, Mayor Lumumba implemented a sales tax increase of 1 percent and levied higher rates on water and sewage. The increases were painful options taken amidst a climate where the city was threatened with further abandonment by businesses and people in higher tax brackets. Mayor Lumumba took the issue to the city, according to his mantra that “The people must decide.”

Another component of the plan is building a solidarity economy through cooperatives. The state of Mississippi only allows farming cooperatives. The needed bill, presented to the state legislature to allow other cooperatives, was sidelined by Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves.

The refusal of Reeves to send the bill to committee was not the only signal that the Jackson-Kush Plan faced major opposition. Aside from the threats and intimidation by wealthy whites, business owners and politicians in Jackson, the state of Mississippi and the media, there was an attempt to introduce a bill that would have put Jackson under emergency financial management, very similar to what is happening in Detroit. This bill didn’t make it out of committee, but it could be reintroduced, depending on the continued development of the plan in Jackson.

A fulfilling political life

Lumumba’s political history, most importantly in the Black Liberation struggle; his solidarity with other national liberation and progressive movements; and the quiet, intimate moments with family and friends were all on display during the memorial. The political period of the Black struggle in the 1960s and the worldwide international struggle for liberation against colonialism and imperialism helped to rear him as a revolutionary.

Out of the struggle for Black studies in higher education, he became the second vice president of the Provisional Government of the Republic of New Afrika and later founded the New Afrikan People’s Organization and the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement.

He moved to Jackson with the PG-RNA. When its headquarters were attacked, both in Detroit and later near Jackson, members defended it from police and FBI repression.

Following police and FBI assaults and arrests of RNA members, Lumumba returned to Detroit to get his law degree from Wayne State. He legally defended the currently exiled Black revolutionary Assata Shakur; helped to free Black Panther Geronimo Ji Jaga from prison; defended Tupac Shakur; and helped secure the release of Jamie and Gladys Scott. The two Black sisters were framed up for and then convicted of armed robbery, where only $11 was taken. They were given double life sentences. Lumumba and a mass movement were able to win clemency for them, granted by former Gov. Haley Barbour in late 2010.

Throughout his long involvement in the political movement, Lumumba’s militancy and belief in liberation and the need for revolution did not waver. He remained committed, despite media attempts now to temper his resolve.

During the mayoral campaign, Lumumba was lambasted for his political activism. Not once did he apologize or attempt to play down his involvement. He maintained that he was “running on an agenda of compassion, justice and human rights.” He said further, “That’s my story and I’m sticking to it. Free the land.”

The legacy he has left for the movement is to work to build a better world. Therefore, the movement must defend Jackson and continue to make sure the Jackson-Kush Plan goes forward. It is what he gave his life doing.

Mayor Lumumba was the embodiment of the oft-quoted principle stated in the book “Socialism and Man in Cuba” by Che Guevara: “At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love.”