Real voices behind the 1963 March on Washington

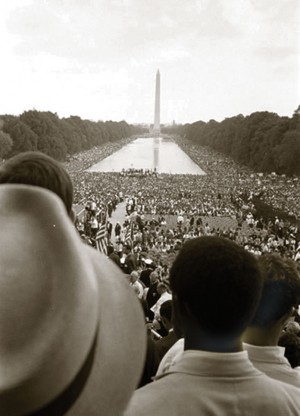

August 28 is the 50th anniversary of that fateful 1963 day in Washington, D.C., when 300,000 people marched and rallied demanding jobs and freedom. Although the corporate media often reference this monumental historic event, the actual march, the circumstances leading up to it and the organizations and personalities represented have largely been lost in people’s public perception in the United States.

Typically a 10-second clip of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final speech of the day is presented, where he says, “I have a dream.” This was of course the greatest speech of that day, summing up the mass sentiment.

Other talks addressed the demands of the movement that had grown out of decades the African-American people’s struggle for equality and self-determination. Even important and key aspects of Dr. King’s speech require modern reexamination in light of the developments in 1963 as well as what is happening in 2013.

King noted that the U.S. government had given African Americans a bad check that had been sent back marked “insufficient funds.” He also illustrated how Southern governors then utilized “nullification and interposition” to block the enforcement of Civil Rights and labor laws.

A historic legacy of mass mobilization

Some 22 years prior to the 1963 march, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin had planned a “March on Washington” demanding the end of segregation in the war industry, which was building up ferociously in early 1941. Randolph, a Socialist organizer, labor tactician and newspaper editor, called for 10,000 to come to Washington on July 1, 1941.

The call for a “March on Washington” in 1941 prompted President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802, which established the Fair Employment Practice Committee on June 25, just six days before the scheduled demonstration. After Roosevelt’s executive action, organizers called off the march.

Although there were other ideas about calling for marches on Washington during the 1940s, none ever materialized. On May 17, 1957, the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom was organized by Randolph and Rustin and supported by the newly formed Southern Christian Leadership Conference headed by Dr. King. At the Lincoln Memorial gathering, featured speakers included New York Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr., NAACP Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins, Dr. King; gospel recording artist and Civil Rights Movement supporter Mahalia Jackson performed.

This rally was designed to support the Civil Rights Act of 1957, which empowered the Justice Department to pursue cases involving the suppression of voting rights of African Americans. Some 25,000 at the event heard Dr. King deliver one his first national speeches, this one entitled “Give Us the Ballot.”

After 1960, the Civil Rights Movement took on a more mass character when the student sit-ins began in the South and the people of Fayette County, Tenn., tested the 1957 Civil Rights Act and began to register to vote, provoking their evictions by white landowners. The student sit-ins and boycotts lead to the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The Fayette County struggle prompted the first Tent City of the period where African Americans camped out to oppose racist evictions.

Nonetheless, the events of the spring and summer of 1963 were critical in the introduction by President John F. Kennedy of yet another Civil Rights Bill in June of that year. The initiative was clearly a response to mass actions in Birmingham, Ala.; Cambridge, Md.; Somerville, Tenn.; Danville, Va.; Detroit and other cities and rural areas across the country.

In Detroit on June 23, hundreds of thousands marched and rallied in the “Great Walk to Freedom” where Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech was first recorded and publicized by Motown Records. His Washington, D.C., version of the same address has gained greater exposure over the last five decades, but was not the first such talk.

Other key speakers at the March on Washington included SNCC Chairperson John Lewis, whose speech was considered so militant that the lead organizers requested he revise it. His original draft states, “We march today for jobs and freedom, but we have nothing to be proud of, for hundreds and thousands of our brothers are not here. They have no money for their transportation, for they are receiving starvation wages or no wages at all.

“In good conscience, we cannot support wholeheartedly the administration’s civil rights bill, for it is too little and too late. There’s not one thing in the bill that will protect our people from police brutality.”

Lewis also generated controversy when he stressed, “We are now involved in a serious revolution. This nation is still a place of cheap political leaders who build their careers on immoral compromises and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic and social exploitation. What political leader here can stand up and say, ‘My party is the party of principles?’ The party of Kennedy is also the party of [racist Mississippi Senator James] Eastland. The party of [Republican Senator Jacob] Javits is also the party of [rightist Senator Barry] Goldwater. Where is our party?”

Bayard Rustin, often recognized as the actual organizer of the March on Washington, read the demands of the gathering. These demands included that effective Civil Rights legislation be passed immediately with no compromises, encompassing full voting rights, the withholding of federal funds to any local and state government that refuses to obey federal Civil Rights laws, the signing of an executive order ending housing discrimination, full employment, an increase in the minimum wages and other issues.

Women, civil rights and the March on Washington

Women played a leading role in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Rosa Parks’ arrest on Dec. 1, 1955, for violating the segregation laws of Alabama set off the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Without the organizing work of the Women’s Political Caucus in Montgomery, which printed the leaflets and circulated them, telling people to refrain from riding the city buses, the boycott would never have been successful. Ella Baker, a long-time organizer in the Civil Rights struggle, was the first executive director of SCLC, and would later encourage the youth to form their own organization, SNCC, in order to ensure the militancy of their anti-segregation campaigns.

By 1963, women were playing leading roles in Cambridge, Md.; Somerville, Tenn.; and within the ranks of SNCC. Yet at the actual March on Washington, only one woman spoke to the crowd, although Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, Joan Baez and others performed.

Dr. Dorothy Height, of the National Council of Negro Women in New York, was on hand but was not allowed to address the crowd. Mahalia Jackson, who had performed, encouraged King during his prepared speech to veer away after the gospel artist shouted, “Tell them about your dream, Martin.”

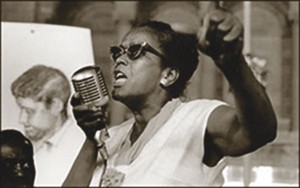

The only woman who spoke during the rally was film star and stage performer Josephine Baker, who flew in from her adopted home of France to participate. Baker’s tenure in France largely resulted from the national discrimination facing African-American artists in the U.S. during the 1920s and 1930s.

Baker told the crowd, “I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents, and much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out, ’cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world. . . .

“I am not a young woman now, friends. My life is behind me. There is not too much fire burning inside me. And before it goes out, I want you to use what is left to light the fire in you.”

After the demonstration Baker wrote to King, saying, “I was so happy to have been united with all of you on our great historical day. I repeat that you are really a great, great leader and if you need me I will always be at your disposition because we have come a long way but still have a way to go.” She signed the Aug. 31 letter, “Your great admirer and sister in battle.”

The full dimensions of the March on Washington need further exposure to the masses in the U.S. Even today in 2013 there is a need for a march for jobs and freedom.

Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois died on the same day that the March on Washington took place. His death was announced at the rally as well as an acknowledgment of his shift to the left in his later decades. Du Bois spanned the political spectrum from Civil Rights and Pan-Africanism to world communism.

All these currents and their glorious histories have much to inform us about the struggle that we need to wage in the years to come.