Chile’s Miguel Enriquez, a fruitful life that endures in time

The author is an anti-imperialist soldier, diplomat and political analyst living in Venezuela. In this article, written Sept. 4, 2024, he celebrates the life and struggle of a Chilean revolutionary, Miguel Enríquez, leader of the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR), which will be the topic of an upcoming forum in the Bronx, New York. The article is important for keeping the memory of a revolutionary fighter alive, and because some of the lessons of that struggle might be useful in the defense of Venezuela from the assault by U.S. imperialism. Translation: John Catalinotto.

Miguel Enríquez, 1944-1974.

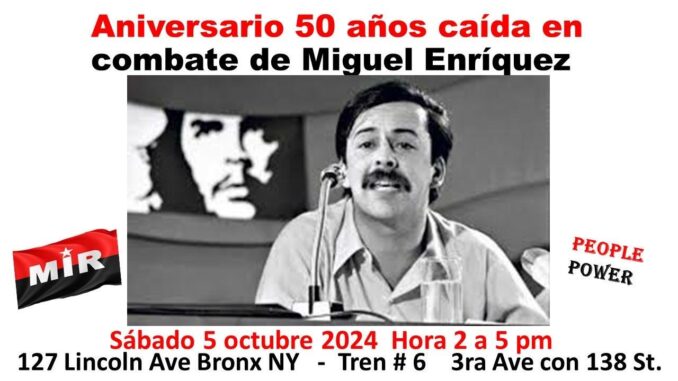

October 5 is the 50th anniversary of the death in combat of Miguel Enríquez, Secretary General of the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR) in Chile. A few years ago, in commemoration of this anniversary, I was invited to speak at an event. With a “memory aid” from that speech, I again take up that task, updating it for a much-needed tribute to the life and work of Enríquez.

I do not want to descend to a fake originality that might lead me to utter fatuous words or rehash commonplaces and repeat the non-committal phrases that characterize those speeches in which the life and work of a popular fighter are commemorated and then, in everyday life, do the opposite of what has been implied by the speech.

I do not come just to say “honor and glory to his memory.” Rather, I will allow myself to use the fiery phrase of a great Venezuelan revolutionary, Jorge Rodriguez Sr., who in October 1975, for the first anniversary of Miguel Enriquez’s fall in combat, delivered a speech at the Aula Magna of the Central University of Venezuela. He said: “To pay homage to Miguel Enriquez means for revolutionaries in Venezuela and anywhere in the world a commitment and an indispensable duty … to commit oneself to work seriously for the development of the tools of combat for the oppressed peoples of the world. … ”

Forty-nine years have passed since that memorable date and 50 since Miguel Enríquez’s last battle on Santa Fe Street in the San Miguel district of Santiago de Chile. The situation of the world, of Latin America, of Chile and of Venezuela has changed, but the impact of his example is still present, as witnessed by the dozens of events that are taking place during these days in Chile and other countries.

In some sectors, however, the idea persists that the Revolutionary Left Movement, of which Enríquez was Secretary General, adopted ultraleft positions that played a decisive role in the fall of the Popular Unity (UP) government presided by Salvador Allende. Those ideas were present and are still present in Venezuela. I believe it is worthwhile to outline some reflections in this regard as a tribute to Miguel Enríquez on the 50th anniversary of his physical disappearance.

The hackneyed accusation that the MIR was considered an ultraleft organization forces us to establish a definition of what “left” is, in order to give such characterization its proper dimension, especially because it has been taken out of context in a self-interested way.

For there to be an ultraleft there must be a left. In the Chile of 1973, there were undoubtedly organizations that embraced life from that political position. However, the most accurate diagnosis of what was going to happen and what happened was the one made by the MIR led by Miguel Enríquez. It’s another thing that this movement was unprepared to successfully face the situation created, when it was supposed to be prepared.

‘Now it is your turn, Miguel!’

It should be remembered that even President Salvador Allende believed in this possibility when, during the defense of La Moneda [presidential house] on Sept. 11, 1973, he instructed his daughter Beatriz to communicate the following message to Enríquez: Now it is your turn, Miguel! The Secretary General of the MIR himself had expressed his point of view regarding the situation and the palpable possibility of a coup d’état in the speech he made at the Caupolicán Theater in Santiago [Chile] on July 17 of that year.

Nothing, however, detracts from the undoubted subsequent contribution of the MIR to the end of the dictatorship. Miguel Enríquez set an example of consistency that was present until the last day of the civilian-military government which, defeated in 1989, continues to exert a powerful influence on Chilean politics to this day.

I must admit that from my modest position as a high school student at that time, I was a staunch adversary of the MIR. It was in the trenches of combat in the war of liberation of Nicaragua in 1979 when I realized the futility of that animosity, which had been built self-servingly by leaders of the traditional Chilean left. I discovered only in 1979 that the MIR militants were comrades of extraordinary conviction and deep-rooted values of solidarity and struggle.

All this to say that those of us who placed ourselves on the “left” and who characterized the MIR as an ultraleft organization were not far from assuming — in spite of the differences — mistaken positions regarding the definition of the main enemy, which definition would allow the establishment of a correct policy of alliances to join forces in diversity — in order to confront the empire and its local lackeys from a stronger position.

It is worth saying that in today’s Chile, many of the leaders of that time, including those of the MIR and those of all the parties that were part of [Allende’s] government of Popular Unity, are now part of the system created by [dictator Gen. Augusto] Pinochet, and they benefit from it. This shows the insignificance of the debate of those years when it is discovered today that some of them aspired to the same thing.

The desperation to be part of the government is today stronger than any conviction and any ethical behavior that could have been followed in the glorious years of the Popular Unity, going as far as to establish agreements with the promoters of the coup d’état. These are the same ones who are currently attacking Venezuela at any international forum, the same ones who supported the 2002 coup d’état against President Hugo Chávez, the same ones who were successful in Cúcuta in 2019 [the attempted coup against Venezuela from Colombia supporting the U.S.-backed Juan Guaidó], the same ones who actively participated in the Lima group [of Western Hemispheric countries backing Guaidó].

It is worth saying that Chile’s current government — characterized as “center-left” — maintains the neoliberal practices cemented by the Pinochet dictatorship, which paralyzed Chile’s popular mobilization of 2019 and sabotaged the call for an original constituent assembly that could legally overthrow the constitutional system created by the dictator [Pinochet], and it has become a fierce repressor of students, workers and Indigenous Mapuche people.

Seen in this way, we could ask ourselves, who was, who used to be and who is of the left, who is ultraleft and who is a reformist left with no capacity for seizing power, who wasted the potential for participation and popular organization generated by the UP government? From another perspective, one might accuse the parties of the traditional left of being the main people to blame for the coup d’état. Neither the one nor the other is correct; that would be a simplistic caricature of the political and social struggle.

The role of U.S. imperialism

To assume such a superficial and crude analysis means to underestimate the incredible destabilizing potentialities of the empire that uses all political, economic and military instruments to reverse the course of history. The real explanations of the coup d’état must be sought in this, and in the inability of the popular movement to build a correlation of forces that could advance the process of change without making a mistake as to who was the main enemy. In the case of Chile in 1973, certainly the MIR could not be placed in that category.

Miguel Enríquez grew tired of outlining a proposal of organization and struggle for the Chilean workers and people. He had done so in countless interviews, speeches and letters since long before the coup d’état and even before President Allende came to power. Of course, he was fiercely attacked from the right and demonized as profane by the traditional left.

After Sept. 11, 1973, as early as Feb. 17, 1974, the “Guideline of the MIR to unite forces ready to promote the struggle against the dictatorship” was published. With the MIR still under the leadership of Miguel Enríquez, the document stated: “The fundamental task is to generate a broad social bloc to develop the struggle against the gorilla dictatorship until it is overthrown. For this it is necessary to unite all the people in the struggle against it and, at the same time, it is strategically necessary to reach the maximum degree of unity possible among all the political forces of the left and progressives willing to promote the struggle against the gorilla dictatorship.”

The “guideline” proposed the creation of a Political Front of Resistance to which it called for the participation of the political parties of the UP, the MIR and the sectors of the Christian Democratic Party (PDC) willing to fight the gorilla dictatorship.

At the same time, the “guideline” proposed to build unity on the basis of an immediate platform with three objectives: the unity of all the people against the gorilla dictatorship, the struggle for the restoration of democratic freedoms and the defense of the standard of living of the masses. This broad platform allowed the incorporation of all the sectors that were really against the dictatorship.

Venezuela today

Today one could establish common elements between that situation and the one facing Venezuela today, the most important of which is the manifest intention of the United States to repeat in Venezuela what it accomplished in Chile 51 years ago. In both cases, local lackeys slavishly bow to imperial interests and assume terrorist postures to achieve their objectives. Likewise, in both cases, applying a correct policy of unity would have led or is leading now to the accumulation of forces necessary to advance.

It is valid to have opposed or challenged the Chilean MIR and its proposals of struggle in the 1960s and 1970s, but it is necessary to have a clear vision to recognize the undeniable moral and ethical value of Miguel Enríquez. Only his revolutionary determination made him stay in Chile after the establishment of the dictatorship, to assume a role in the leadership of the resistance forces. The attitude of the MIR cannot be separated from that of its Secretary General.

Miguel Enríquez was the most visible figure of a constellation of leaders who shaped a very complex stage of the political struggle in which there was a transition from the social Christian reformism supported by the Alliance for Progress [before 1970], to the luminous days of the government of President Allende [1970-73] and from there, to the criminal dictatorship of Pinochet, also supported politically, militarily and economically by the United States and the political framework provided by the fascist right wing and by the Christian Democrat right wing when it carried out an iron-fisted and disloyal opposition to Salvador Allende.

To remember Miguel Enríquez is an act of justice; it is a responsibility to the memory that must accompany the struggle of the peoples; it is to reaffirm that after one stage comes another in which the commitment in the search for a better world is ratified; it is to be sure that his physical absence does not prevent us from sharing with joy the greatness of a man who only lived 30 years, but who will be everlastingly present in the struggle and the victory of Chile and Latin America.

Forum on 50th anniversary of death in combat of revolutionary Miguel Enríquez set for the Bronx, New York, 2 to 5 p.m., Oct. 5.

For the pdf of a pamphlet of WW articles during the Popular Unity government, including an interview with Miguel Enríquez, see workers.org/wp-content/uploads/Chile-1970-1973-reprint2020.pdf.