Newsom’s reactionary approach to mental illness

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a wannabe reformer for mental health, is proposing to expand the ability of the state and counties to commit drug addicts and the mentally ill to treatment. He is suggesting that the state should have the ability to commit anyone with mental illness or drug addiction problems to facilities, ignoring the lack of beds for treatment at all levels, the causes of these conditions and more alternative treatments.

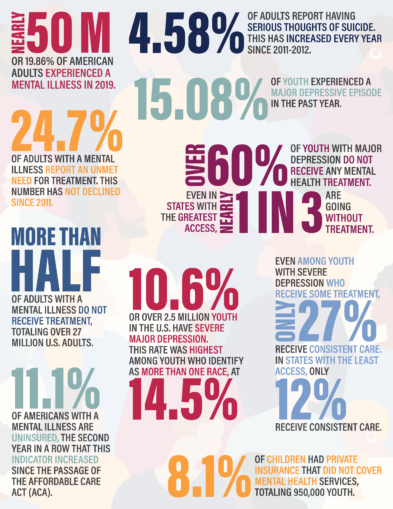

Statistics on state of Mental Health in America report for 2022. (Source: National Alliance on Mental Illness)

The main crisis in behavioral health treatment across the U.S. is a major lack of beds, so forcible commitment for people who experience acute mental illness or accidental overdoses of drugs of abuse is not a realistic solution.

The other problem with forcing addicts and the mentally ill into treatment is that it undoes the efforts of the mentally ill to fight forced incarceration in asylums. While the current model of mental health treatment forces most mentally ill people into prisons, recreating the asylum system is not the solution.

What Newsom is proposing is a major step centuries backward in the treatment of mental health.

Historic abuse of people suffering mental illness

In the United States, how society views those with mental illness has shifted over time. Initially, they were viewed as “demonically possessed,” because of the overwhelming dominance of religions. Over time, people with mental illness were viewed as “hapless criminals” who needed to be removed from society. This resulted in the mentally ill being incarcerated. As time marched on, however, the ideas that the mentally ill were criminals or demonically possessed went the way of the dodo.

One of the first people to view those with mental illness as sick was Dorothea Dix. Having a father who was alcoholic and depressed allowed Dix to see mental illness for what it was: an illness. She believed that incarcerating the mentally ill in jails and prisons was inhumane, as was the treatment of the mentally ill in general.

Her efforts to create hospitals in the United States to house the ill was successful in the era before there were psychiatric medications. Seeing how the mentally ill were abused in prisons and jails, Dix went across the United States and Europe to push for investment in mental hospitals.

Cruelty of the lobotomy

But was the institutionalization of mentally ill people necessary? At the time, with no effective treatments for illnesses like schizophrenia spectrum disorders or mood illnesses, there was nothing that could be done to treat the mentally ill. Doctors used to argue for the effectiveness of psychosurgery (lobotomy), but these surgeries were both ineffective and torturous for the patient undergoing them.

The main reason they argued for lobotomies was because it was easier to take care of a lobotomized patient than it was to take care of a patient who was actively mentally ill. A large number of lobotomy victims were also either gay or people of color.

To add insult to injury, the inventor of the lobotomy, Antonio Egas Moniz, was given the Nobel Prize for his “discovery.” Even now, as we recognize the cruelty of the lobotomy, the prize’s officials refuse to rescind the award for its invention. The Soviet Union was the first nation to recognize the inhumanity of psychosurgery.

No longer able to take care of themselves, patients who received at lobotomy were almost guaranteed a lifetime stay in a mental hospital. The cruelty of the lobotomy did, in a sense, achieve the goal of keeping the patient from experiencing intractable mental illness, but only because it robbed the patient of their personality and what made them who they were.

It wasn’t until the late 20th century that the abusiveness and inhumanity of the mental health care system was revealed. In addition to lobotomies, there were other forms of cruelty inherent in the commitment system. The patients were not given quality food, were not permitted to see their loved ones and were generally treated like any other prisoner.

President John F. Kennedy, who witnessed his sister Rosemary’s lobotomy and commitment, took a special interest in the treatment of the mentally ill. Before his assassination, he signed laws passed by Congress including the Community Mental Health Act, that would lead to deinstitutionalization.

Other cultural factors, such as the publication of the book “Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates” and the release of the film (and book) “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” led to the change of public opinion against the institutionalization of the mentally ill.

In the 1950s, chlorpromazine (Thorazine) led to the advent of medicinal treatment of mental illness. The use of Thorazine, a novel antipsychotic that treated the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders, led to some people being freed from institutions. The development of even more antipsychotics and antidepressants led to even more releases. While the medicinal treatment of mental illness created some problems, the ability to treat the mentally ill without locking them away was a net positive.

Humanity of conservatorship is in question

While chlorpromazine and other medications made decreasing the number of committed mentally ill people possible, there were other ways for the mentally ill to lose legal control over themselves and their wishes. One was conservatorship that granted control over a person’s affairs to another individual who, ideally, would have their best interests at heart.

Recently, the question of the humanity of conservatorship was called into question regarding pop star Britney Spears. While the affairs of a celebrity ordinarily aren’t relevant to the working class, this case was of interest, because many people didn’t know that having a mental illness could force someone to lose legal control over their affairs.

In California, conservatorships grant a mentally well adult power over a mentally ill child or adult. The conservatorship could be permanent if the patient cannot recover from their illness, but it could be withdrawn if the patient regains control over their illness

Capitalism creates, exacerbates mental illness

The treatment for mental illness under capitalism is made more problematic due to for-profit health care. The majority of people in most capitalist countries, especially in the U.S., lack access to affordable health care. Even if one can afford health care, most policies limit care for mental illness.

It’s well-known that the treatment of mental illness isn’t simply just medicating and moving on; its current practice is to medicate and to give therapy of all kinds to mental health care patients. A major part of progressive treatment is to identify the fundamental causes of mental illness, which is often stress stemming from one’s inability to cope with a repressive political and economic system.

In any given year, around five out of every 100 adults (5%) in the U.S. has post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a serious but treatable mental health condition experienced after a traumatic event or series of traumatic experiences. While awareness about PTSD among veterans returning from war zones is becoming more common, there is less acknowledgement that millions suffer PTSD simply because they are victims of poverty and racism, classism and other forms of discrimination just trying to survive under capitalism.

Socialism is the only real solution to the question of the treatment for mental illness. It would result in all health care being paid for not individually but by the workers’ state and available free for all the people.

Revolution isn’t just economic or political, it’s universal. It changes not just political or economic systems, it changes how we approach everything. We need to move on from asylums and move on from medication-only approaches to treatment. These methods did hold importance in the times they were in place, but now we know better. Now we know that holistic approaches are needed.