Suleiman looking through bars, in Chronicle of a Disappearance, 1996.

One major takeaway of the Palestine Writes literature festival, hosted in Philadelphia Sept. 22 – 24, was the essential connection between culture and politics. In speaker Isabella Hammad’s novel “Enter Ghost,” the creation of art itself becomes a threat to the occupying forces who, to paraphrase her explanation, fear the spontaneity that theater allows. An opening panel called The Cost, Reward and Urgency of Friendship had non-Palestinian artists and writers discussing the experience of solidarity that art can create and foster.

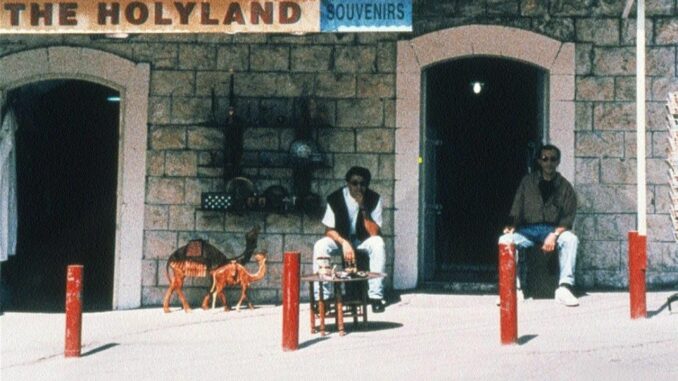

Elia Suleiman sitting with Ali Suliman (right) in Chronicle of a disappearance, 1996.

Palestinian art is particularly essential as an expression of a culture which the Zionist occupying forces and their imperialist allies want to erase from the face of the earth, proof that regardless of the lie that Palestine was “a land without a people,” Palestinians have always been here and aren’t going anywhere.

Elia Suleiman’s 1996 film “Chronicle of a Disappearance” is a potent piece of cinema which provides an intimate, subtle look at the attempts to erase Palestinian identity. It’s divided into two large chapters. The first half falls under “Nazareth – Personal Diary,” and the second half falls under “Jerusalem – Political Diary.”\\

The film is largely minimalist, with long still shots, sparse dialogue, in a documentary style with relatively little traditional plot until the second act. To fully perceive the titular disappearance, it’s important to briefly look at what happens in each act and then circle back to see the full statement being made.

‘Nazareth – Personal Diary’

The film opens, after a long shot of a man sitting asleep, with the first of many typed messages to the audience. These messages appear throughout the film to provide structure and exposition, frequently reading only ”the following day,” but occasionally explaining situations.

Suleiman, back to camera, at Holy Land store, from file, 1996.

In his first communication, Suleiman explains that he woke up after his first night home to the sound of his aunt’s heels. The picture then cuts to an interview-like scene of his aunt preparing to go pay respects, explaining the various pettinesses of another woman towards weddings and engagements in her family. She then leaves in disgust. Suleiman himself remains silent throughout the sequence and, indeed, the film.

The documentary-esque tone continues as various sequences of different places around Nazareth play and repeat, almost exclusively in static shots without music. We see Suleiman’s family in their apartment, a “Holy Land” gift shop that remains entirely unpatronised, a parking lot in which people repeatedly pull in, exit their cars, fight and are made to leave and more.

Outside of some humorous scenes (the parking lot, an argument about peeling garlic), the atmosphere is largely mundane. Some scenes denote isolation, such as Suleiman’s uncle playing online cards and smoking at home, and many sequences in communal spaces are of either conflict or extremely shallow small talk, but this isolation is by no means a hard rule.

The Israeli occupation plays largely a background role here but comes out in some scenes of dramatic irony. A background radio program describing the Serbian-Croatian war which plays at Suleiman’s uncle’s apartment discusses, at length, the “complexities” of redistributing land. The Holy Land store sells postcards labeled “patrolling the border,” which show Israeli Defense Forces soldiers stationed at a barbed wire fence. A drive through the countryside features a conspicuous barbed wire fence in the foreground.

Vignettes portray impact of occupation

Dimitry Osmolov and Igor Paskov (police), in a scene from the documentary, 1996

The rest of the first act follows a series of vignettes — “Appointment with the Priest, Appointment with the Writer, Tel Aviv – A Stroll Along the Beach.” The priest brings the occupation to the foreground, starting with the statement, “That’s where Jesus is said to have walked over water. Now it’s a gastronomic sewer filled with excrement, the shit of American and German tourists who eat Chinese food.”

He points out several large, modern apartment complexes and comments that the dark spaces on the hills were a place which scared and intrigued him, a focal point of a faith which is now gone.

What stands out more and more during the remaining vignettes — particularly in Tel Aviv, where the “stroll along the beach” consists of Suleiman smoking a cigarette by a fountain and leaving — is the intentional disappearance of Palestine under the occupation.

Between the Israeli radio programs and postcards (more and more are visible), the empty spaces between Palestinians in environments that are passed by or treated as oddities (a busload of tourists take photographs of Suleiman and the shopkeeper outside of Holy Land but never attempt to speak to them), and a strange, unreal atmosphere (a book falls from the sky in front of Holy Land. “It’s raining culture,” the shopkeeper matter-of-factly says), Nazareth becomes presented as a ghost town with people still living in it.

This stands out in contrast with the second act, and is reexamined in the conclusion.

‘Jerusalem – Political Diary’

The first act ends with Suleiman watching a slideshow of photographs showing people and places while the second act begins with a long drive down a hill, passing countryside and older stone buildings while conspicuously showing a hill in the distance covered in more modern structures. Music plays for the entire two minute sequence.

In a film which has contained mostly static shots and silence, this is a noteworthy shift, but not the only one. Political Diary is broken up into several labeled chapters and contains much more text than “the following day.” “A Stop at the American colony. People here can’t stand one another.” Descriptions of his renting a flat in Jerusalem. “The hiss of euphoria at the moment of disappearance.”

The second act also contains more of a plot line. While Suleiman moves into a flat, a woman named Adan struggles to find a landlord to rent to her with her Arabic name and accent. Suleiman’s life continues to consist largely of him editing the footage and text of Chronicle and watching the world through his window. There is one sequence where he goes to a meeting hall to speak about his filmmaking, but he is constantly interrupted before speaking by a whining microphone, ringing phones and the attendees leaving.

Suleiman looking through bars, in Chronicle of a Disappearance, 1996.

Suleiman ends up coming across a police walkie-talkie dropped when a van full of police officers peels into a parking lot so they can pee on a wall. He spends several scenes with the broadcast playing in the background. At one point, he hears them preparing to do some sort of action before two officers jump out of his bushes, walk through his house while he impassively follows and leave.

They then describe an itinerary over the radio, ending with him labeled: “some guy in pajamas.” The lack of notice anyone pays him is a repeated motif. He remains a silent observer. If Personal Diary showed a land in disappearance, Political Diary shows a man in disappearance, his Palestinian identity causing him to vanish in the eyes of others.

When Suleiman repeatedly enters a space full of Arabic and Palestinian decor, he stumbles upon a surreal attic stage with a mannequin and a television playing music. Downstairs, he encounters Adan and others. The narrative repeatedly returns to Adan with the same police radio and what appear to be several weapons (actually two lighters shaped like a handgun and grenade). In Personal Diary’s climax, she gets on the radio, pretends to be a member of the police and sends the patrol cars around in a chaotic and random drive that ends with them in a ditch.

She finishes her communications by telling the police to leave Jerusalem. “Jerusalem is no longer unified. Over.” When they finally do raid her space while she watches, one of them comments over the radio that there was some unknown woman present and wonders if she was important. She, too, has been made invisible.

The ‘Promised Land’

The film’s last chapter is described as “the promised land,” and after another driving sequence (this from a much higher camera angle, down a much more empty street), it largely revisits places and people from the Nazareth Diary. Things have changed. Whereas the prior conversation on the fishing boat was primarily trash talking of different families, now the fishermen sing “oh, night of farewell.”

In the parking lot with all of the fights, a car pulls in, driver and passenger switch places wordlessly and peacefully and both drive away. The public atmosphere remains cheerful and friendly, in opposition to the initial tension. Suleiman finally returns to his family’s apartment. His aunt and uncle are once more sleeping before the television, which plays Hatikvah as they snooze on.

“Chronicle of a Disappearance” drops viewers into a perspective showcasing the psychological effects of life under violent occupation and erasure. Suleiman (and, in a small part, Adan) becomes invisible through his Palestinian identity, silent, frequently facing away from the camera. While Adan employs that to her advantage, Suleiman himself remains a largely passive observer. Palestine, too, begins to disappear, with that which is sacred becoming mundane and constant reminders of the occupation in all locations.

Palestine: solidarity vs. disappearance

Nevertheless, solidarity between Palestinian people is present at the film’s conclusion, scenes once full of conflict replaced with joy and mirth. “The promised land” takes shape through the lives of millions of people who have not disappeared and will not disappear.

The final reminder of occupation is slept through, an attempted “last word” which falls on deaf ears. When the occupation finally ends and the displaced return home, the home of Palestinians finally opened in full once more to them, this solidarity and consistency will be the engine.

As a piece of art that builds that solidarity in viewers, this film is essential viewing for all workers and oppressed people. It is, at time of writing, available for streaming on Netflix and available for purchase from Trigon Film.

Raposo is a Portuguese Marxist analyst, editor of the web magazine jornalmudardevida.net, where this article…

By Alireza Salehi The following commentary first appeared on the Iranian-based Press TV at tinyurl.com/53hdhskk.…

This is Part Two of a series based on a talk given at a national…

Educators for Palestine released the following news release on July 19, 2025. Washington, D.C. Educators…

On July 17, a court in France ordered the release of Georges Abdallah, a Lebanese…

The following are highlights from a speech given by Yemen’s Ansarallah Commander Sayyed Abdul-Malik Badr…