Health care is a right – for those behind bars too!

“This is how they treat us!” exclaimed Bryant Arroyo, incarcerated at State Correctional Institute Coal Township in Pennsylvania, He was expressing frustration with his three-year attempt to get effective treatment for severe psoriasis in his ankles.

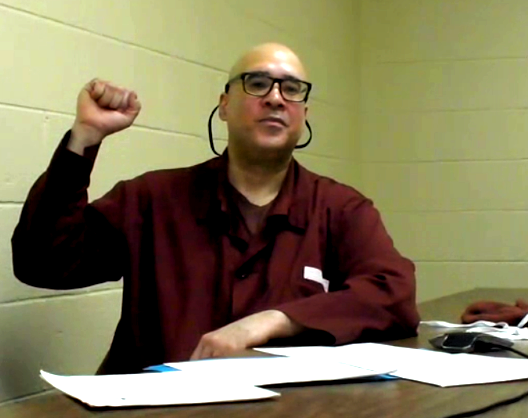

Arroyo during an online call Feb. 3, 2021. Credit: Joe Piette

On April 7, Arroyo had a scheduled mandatory medical call at 1 p.m. He had a pre-scheduled Law Library session in the morning; but when back to his cell, he was told he had missed his medical appointment. The Medical Department had rescheduled to an earlier time, but no one informed him. Guards could have reached Arroyo at the Law Library but didn’t. As a result, his appointment was rescheduled, and treatment was delayed once again.

Earlier in May, Arroyo’s cellmate Alex Machado, suffering from chronic asthma and out of inhaler medicine, requested a sick-call appointment but got no response. He suffered severe coughing for several days, until his mother’s repeated calls to the prison resulted in his being given the lifesaving medicine.

Just how difficult it is for incarcerated people at SCI Coal Township to get adequate health care is similar to how almost 2 million people behind U.S. prison walls are treated, according to a report entitled: “Health Care Behind Bars: Missed Appointments, No Standards and High Costs,” by Vera, a New York-based, anti-mass incarceration organization. (tinyurl.com/4ccjzbv7)

Routine care denied

In 2022 the New York Supreme Court found the New York City Department of Correction in contempt for failing to comply with an earlier order to provide people in its custody with access to basic medical services. Corrections officers often report incarcerated people as declining treatment that they were in fact never offered.

The lawsuit filed by New York City public defenders and pro bono associates listed more than 1,000 instances in December 2021 alone, in which someone incarcerated at a Rikers Island jail did not make a scheduled medical appointment, because a corrections officer had failed to escort them. (tinyurl.com/3h5rrdvh)

The New York court’s ruling highlights the denial of basic care, which plagues jails and prisons across the U.S. In state prison facilities, according to the American Journal of Public Health, more than 20% of incarcerated people with a persistent medical condition go without care. (tinyurl.com/8y3zm444)

People from impoverished backgrounds and people of color, who make up the majority of incarcerated populations, are more likely to suffer from chronic health conditions like heart disease, asthma and diabetes, making inadequate care in prison more likely to result in premature death. (tinyurl.com/5a69xddn)

Wheelchair cruelly removed

On April 19 Arroyo’s wheelchair was cruelly taken away by RN Linda Jones and RN Heather Britt, and he was uprooted under threat of being placed in the Restricted Housing Unit (solitary confinement) if he didn’t voluntarily get out of the wheelchair. Arroyo was not given a crutch, a walker or even a cane to help counterbalance the pressure of his weight on his severely inflamed sore ankles. He had to limp back to his cell with the help of another incarcerated person, Joseph Cruz.

Six months earlier, Arroyo had many biopsies performed, resulting in several stitches on both ankles. Despite complaints about pain, he has not received any oral medication since then.

On April 25 Arroyo was seen by Physician Assistant Davis, who insisted on prescribing the same ineffective generic topical cream prescribed last year. Arroyo refused the ineffective, costly ointment.

In Pennsylvania prisons, each visit to the medical unit or for a virtual telehealth call costs $5. Each prescription costs an additional $5. Incarcerated workers in Pennsylvania prisons only earn 23-to-50 cents per hour, forcing them to consider costs before seeking treatment or a prescription. (tinyurl.com/3yaphrp8)

Arroyo was seen by Dr. John Hochberg on April 26, when he noticed his wheelchair was still folded and parked in the same medical unit. In response to Arroyo’s complaint about losing his wheelchair, Hochberg stated: “This is what you get when you publish articles on health care.” He refused Arroyo’s right to a walking aid; Arroyo limped away in pain. (Hochberg was referring to the Workers World article “Health care in prisons is a crime,” workers.org/2022/12/68201/.)

On May 15, Arroyo was given a virtual visit by dermatologist Stephen Schleicher, who exclaimed: “Whoa, this is way too long!” when told how long Arroyo has been waiting for follow up since the biopsy. Schleicher prescribed a new topical cream and scheduled an appointment for an injection May 18.

Incarcerated workers have right to Medicaid

The National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC) sets standards and offers accreditation to jails and prisons for health care services. (tinyurl.com/yxy7832e) Participation is optional, and the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections isn’t listed as a participant. In fact, just 17% of prison facilities (500 of 3,000) in the U.S. are accredited. The NCCHC opposes co-pays for health care for incarcerated people. (tinyurl.com/yvanvbvw)

Medicaid provides health coverage for low-income people who qualify based on income, disability status and other factors. Most incarcerated people would be eligible for Medicaid, since people in prisons and jails are among the poorest populations and have high rates of disabilities. (tinyurl.com/2wdntmhy)

Yet, Medicaid rules deny those health care rights to the incarcerated. Eliminating those restrictions would give incarcerated people more access to health protection, as stipulated in the landmark Supreme Court case Estelle v. Gamble, 1976. The ruling established that failure to provide adequate medical care to incarcerated people as a result of deliberate indifference to serious medical needs violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

Health care is a right, including for those behind bars!