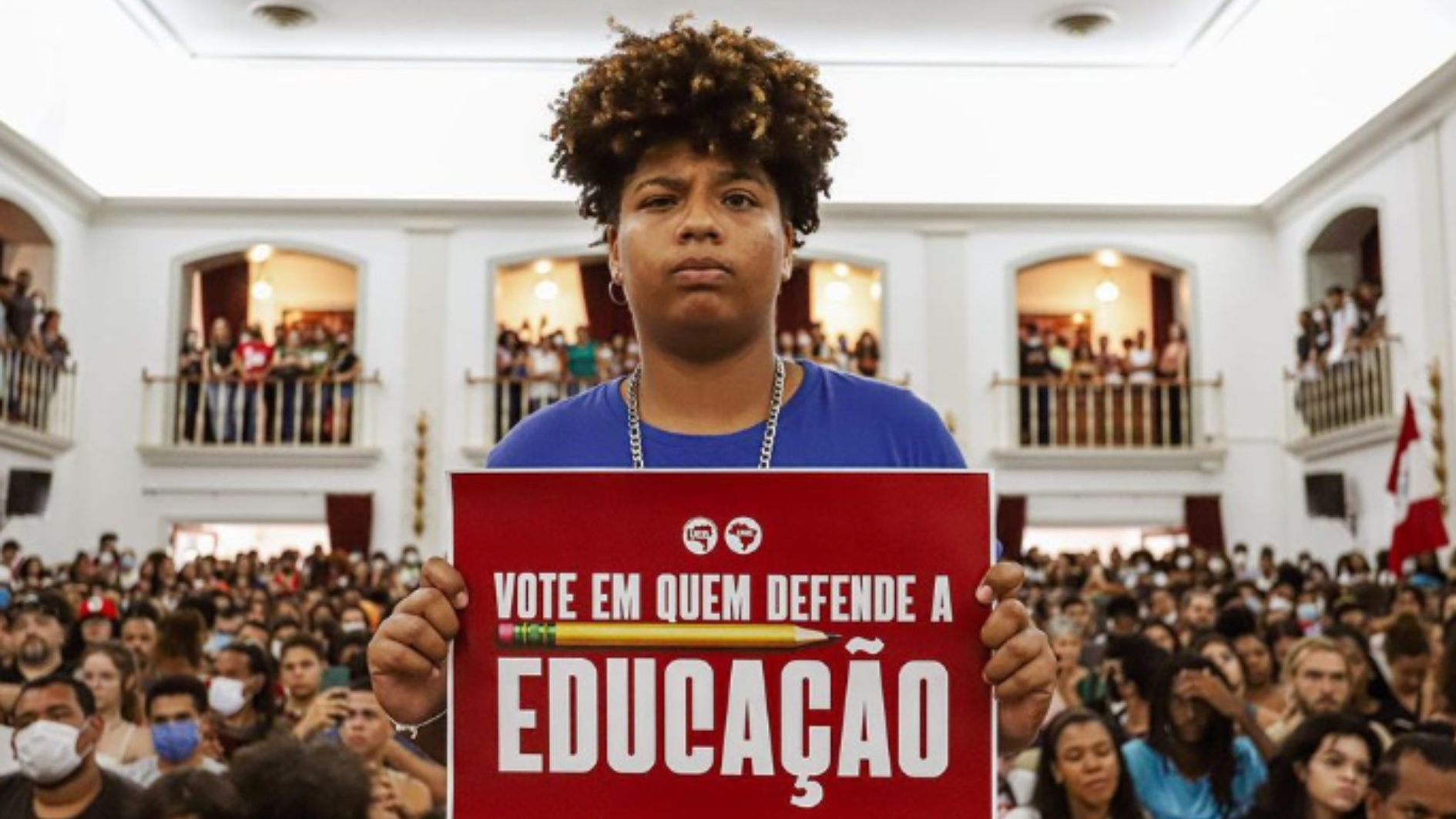

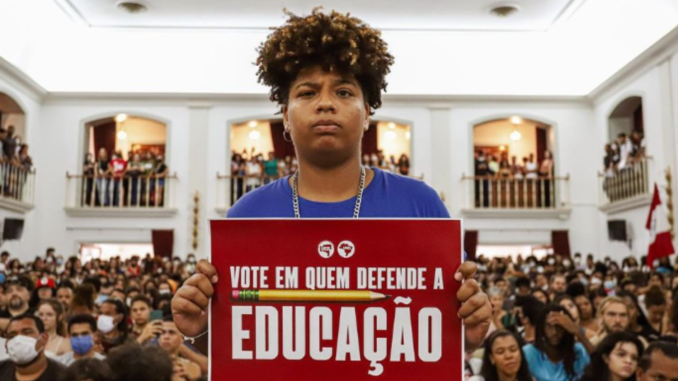

The battle for education rights is only one of the struggles against the Bolsonaro regime. ‘Vote for defenders of education’ reads the poster.

By Sergio Ortiz

Ortiz, an Argentine Marxist-Leninist and a leading member of the Party of Liberation (PL), published this analysis of Brazil’s national elections Oct. 8, 2022, on his website. Translation: John Catalinotto.

The Oct. 2 first round of Brazil’s elections had a rare mix of positive and worrying aspects, enough to leave a trace of bitterness in the celebrations of the PT [The Workers’ Party, or Partido dos Trabalhadores] and its 10-party coalition.

The battle for education rights is only one of the struggles against the Bolsonaro regime. ‘Vote for defenders of education’ reads the poster.

The good part was [Luis Inácio Lula da Silva] Lula’s victory, with his goal to return to the Planalto Palace for four years. He obtained 48.37% of the votes (57. 3 million votes) against 43.35% (51.1 million votes) of the incumbent Liberal Party president, an advantage of 6.2 million votes.

The bitter taste for the winners arose because they had insufficient votes to win in the first round, needing 50% of the valid votes plus one. And they did not reach that goal, despite the fact that many of the 50 pre-election opinion polls agreed that a runoff would be unnecessary.

This new rejection of the pollsters also entered into the political balance, regarding the reasons for such mistakes. That the people polled are ashamed to say who they vote for. That they change at the last minute. That the studies are made on social strata not proportional to the electorate.

That these companies seek the approval of those who pay for their jobs, etc.

Anyway, the polls in Brazil were a total fiasco, in coincidence with Argentine realities. The crises of the bourgeois democracies of dependent capitalism also have this repeated characteristic of erratic polls.

The Petista disappointment — and that of left-wing and progressive sympathizers in Latin America — had not only to do with the frustrated expectation of seeing the former metallurgist president on Oct. 2, without having to suffer until the second round 28 days later. There were other negatives, such as the growth of Jair Bolsonaro’s vote. In numbers he had 1 million more votes than when he was elected president in 2018.

Bolsonaro now won in Brasília (the capital) and the two most important states, São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. His candidates won the governorships of most of the 27 states, in some cases in the first round, and in others, such as São Paulo, they are favorites for the runoff. Their caucuses in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate will be the largest, with the worrisome conclusions that this implies for Lula should he win the presidency.

On the offensive . . . or at half speed?

Progressive and reformist forces are usually left halfway, when it comes to political confrontation with the conservative blocs. First, they avoid mobilizing popular sectors to play their fundamental role in the streets against the ruling classes. To a great extent, this is done to avoid conflict with the ruling classes, which are the owners of the fundamental levers of a country.

Consistent with this “calm” discourse and assuming that they have already won an election, they avoid hitting their electoral rivals hard, aiming to sponsor a senseless “national unity,” which the enemies of the people would ignore.

Bolsonaro called Lula everything from a convict, corrupt and communist to accusing him falsely of wanting to close churches and attack families. All these lies were in line with Bolsonaro’s motto of “God, Homeland, Family and Property.”

It was not only words and violent use of social networks and media. Bolsonaristas murdered three PT sympathizers in the weeks prior to the election, opening a serious risk of what those fascists could do in case, at the end of the month, a defeat of the retired military man takes place.

The PT did not even hit hard on the health catastrophe experienced by Brazil with the coronavirus, which killed 687,000 people. The beast said it was a gripezinha (little flu) and did not buy vaccines in time. This flank was not sufficiently hit, and General Eduardo Pazuello, former Minister of Health and co-responsible for that crisis, won a deputy seat for Rio de Janeiro.

Only in the final stretch of the campaign, and in one of the three televised debates of the candidates, did Lula criticize Bolsonaro’s policy during the pandemic, but it was not part of a general offensive.

The PT campaign command and its allies also avoided deepening the political denunciation of Bolsonaro’s embodiment of fascism and his political and military core (in addition to relying on the armed forces, he incorporated more than 6,000 military personnel in government functions).

The opposition’s timidity left, for many voters, the taint of corruption on Lula, rather than on Bolsonaro. During the two governments of Lula and Dilma Rousseff, there were cases of corruption via bribes from Odebrecht [a Brazilian conglomerate], but neither Lula nor Dilma were corrupt. The former spent 19 months in prison between 2018 and 2019; but his convictions were overturned in 2021 because the trials had been rigged by Judge Sergio Moro, who was awarded by Bolsonaro with the Ministry of Justice and now with a senatorial seat.

The current president has many accusations of corruption, both with his three sons, two of them legislators, and throughout his passage through nine different right-wing parties between 1989 and 2022 (data from Gustavo Veiga in Tearing Down Walls) and as president from 2019 until today. And yet many voters still believe Lula is the dishonest one!

And that is not explained only by social networks. What’s basic is the passivity of progressive-reformist movements, which out of “political correctness” avoid attacking the enemy. Meanwhile, this right wing plays hard, on the offensive, and that’s why it regains ground — as Bolsonaro has in recent months.

This is what Bolsonaro’s friend [former Argentine President] Mauricio Macri did, who had lost by 15 points in the first round of August 2019 and redoubled his attacks on the Frente de Todos and gained 8 points that October. Macri lost, but was left standing to seek his revenge, something that is currently maturing in Argentina. And isn’t it what Bolsonaro could do, even if he loses Oct. 30?

You may win but you will not govern?

Everything should indicate that Lula will be elected president on Oct. 30. The discredited polls put him ahead again by 10 points. The candidates who came in third and fourth place, Senator Simone Tebet of the center-right MDB [Brazilian Democratic Movement] and Ciro Gomes of the Labor [Democratic Workers Party], have called on their followers to vote for Lula.

Among the few hopes for the neo-Nazi are two: the evangelical churches, which are part of his electoral strength; and the Auxilio Brasil plan, which provides social aid of US$120 to 20 million very poor families. Obviously this state bonus increased his votes in the first round and could improve them in the runoff, but not so much to discount the difference of the 6 million votes in the first round and the 7% that Tebet and Gomes could bring to Lula.

Should Bolsonaro be defeated, we can expect anything. As his political center is Donald Trump, anything includes an attempt to take over the Capitol, as did the U.S. neo-Nazis who denounced Joe Biden’s victory as a fraud. Something like that cannot be ruled out; although as a disciple of the tycoon, the South American fascist can also evaluate that it would be more convenient for him to unite his forces and wait.

Bolsonaro will have half or more of the governors of the country, a majority of 273 deputies (among his own and allies) against 128 of the PT and allies, a majority in the Senate counting his own and allies, etc.

If instead of imitating the first incendiary Trump, he chose to copy the second Trump, the one who waited for Biden’s attrition to position himself as Republican leader for November’s midterm elections, Bolsonaro can be even more dangerous. This is what Macrismo did in Argentina, whether Macri or someone else is the candidate in 2023. And this happens just with the emergence of right-wing governments in other countries, such as Meloni in Italy and Truss in Britain.

If Bolsonaro were to adopt this tactic, he will be betting on not letting the PT govern.

Lula pivots to the center-right

By choosing Gerardo Alcklim, a right-wing politician, as his vice-presidential candidate, Lula copied himself and [Argentina’s] Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. Himself, because he previously put as his vice-president José Alencar (Liberal Party) and encouraged Dilma to do the same with Michel Temer (MDB), who ended up staging the parliamentary coup d’état in 2016 and opened the way to Bolsonarism two years later. And Cristina Fernandez, who did something similar with Alberto Fernandez as a gesture to the electorate and to the real power of dependent capitalism.

Lula’s developmentalism combined social policies, which lifted 30 to 40 million people out of poverty, with economic policies favorable to the monopolistic industrialists of São Paulo (FIESP) and bankers like Henrique Meirelles, owner of private banks and head of the Central Bank during most of Lula’s government, later Finance Minister of the pro-coup Temer.

From that very politically limited progressive government, today Lula comes with a more center-right proposal. Proof? We have already indicated that his campaign preaching was less than light in the face of an enemy that was hitting below the belt. He did not make important programmatic proposals to fight poverty, for example, to tax the richest and bankers more.

On the contrary, he had meetings with Brazil’s business leaders, seeking to reassure them that with his new government, they have nothing to fear. On the other hand, he has met with envoys of the Biden administration; and Sept. 21 he met with Douglas Koneff, the chargé d’affaires in charge of the U.S. embassy in Brazil.

It is well-known that Lula would not inherit the drowning country that the Frente de Todos inherited [in Argentina]. It is said that its Central Bank has reserves of $360 billion. Its annual inflation will be less than 10%. The GDP has been growing, albeit modestly, but with the same tremendous inequality as always: a lot of poverty and 33 million citizens who do not eat well, with Indigenous peoples subjugated and the Amazon forest cleared.

Brazil, like Argentina, needs a popular, democratic and anti-imperialist solution. Here there was neoliberalism with Macri, and there neo-Nazism with Bolsonaro. It is obvious that Cristina is not the same as the CEO of the PRO [Macri], nor is Lula the same as Bolsonaro, but the drama is that the limits and cowardice of those fronts, which were once progressive and retain a modest part of it, opened the doors to the return of the vicious right wing, one with a business face and the other with a military face.

This statement was recently issued by over 30 groups. On Friday, March 28, Dr. Helyeh…

When Donald Trump announced massive tariffs on foreign imports April 2, Wall Street investors saw…

The century-long struggle to abolish the death penalty in the U.S. has been making significant…

Download the PDF May Day appeal to the working class Revolutionary change is urgent! Gaza…

Philadelphia On March 26, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court denied political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal permission to…

There are two important and overlapping holidays on April 22: Earth Day and Vladimir Lenin’s…