Early gay liberation: Anti-racist solidarity

Part 76 of Feinberg’s Lavender & Red series on the intersection of LGBTQ2S+ and socialist history appeared Oct. 7, 2006, in Workers World newspaper, which published the 120-installment series between 2004-2008.

One particularly militant action by a multinational group of gay men took place during the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention in the fall of 1970, convened by the Black Panther Party. It included a demonstration of anti-racist unity.

Leslie Feinberg at Syracuse, New York, Pride, June 15, 2013. WW Photo: Minnie Bruce Pratt

During the convention, a group of four gay men — two Puerto Rican, one African American and one white — at least one of whom was reportedly wearing “a bit of makeup,” went out to eat at an area restaurant.

Management at the restaurant, which reportedly catered to a white clientele, refused to serve the group. The four left and returned with 30 or more gay men. The restaurant boss ordered them out.

According to a report in the Advocate: “A fight erupted when management, security guards and several patrons attacked one Puerto Rican and two [B]lack Gays. Glasses were thrown, windows broken and other damage done in the free-for-all which developed.” (Donn Teal, “The Gay Militants”)

The other gay men of various nationalities came to their aid and fought alongside them.

After the group left the restaurant, police stopped 12 of the gay men as they drove away and charged them with assault, illegal entry and destruction of property. The defendants later won an important legal precedent — the right to vet prospective jurors about their prejudices against same-sex love. Ultimately the charges were dropped.

More solidarity

As early as November 1969, left-wing gay liberationists actively organized in support of Chicanx/Mexicanx grape pickers who were trying to organize a union — the United Farm Workers (UFW) — in the fields of California. The “Radical Caucus” at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations won a resolution in support of the farm workers, even though the convention had drawn more moderate forces.

Renowned labor leader César Chávez continuously extended his hand of solidarity to gay liberation, as well.

In summer 2005, when the National Executive Board of the United Farm Workers — a predominantly Latinx union — announced its principled stance in support of the right of same-sex marriage, UFW Southern California Political Director Christine Chávez restated her grandfather’s support of gay rights.

She recalled: “Beginning in the 1970s, before there was widespread public acceptance of gays, especially among Latinos, my grandfather, César Chávez, spoke out strongly for gay rights. He attended gay rights rallies and marches. He brought with him the UFW’s black-eagle flags and farm workers who wished to participate.” (ufw.org)

Chávez helped carry the lead banner in the 1979 march on Washington for lesbian, gay and bisexual rights.

Early gay liberation won support from Puerto Rican revolutionary youth as well, particularly from the Young Lords Party.

When Gay Liberation Front (GLF) activists went to a Puerto Rican street festival on Aug. 8, 1970, sponsored by the Young Lords Party, members of the Puerto Rican revolutionary youth party helped hand out leaflets advertising an upcoming GLF dance. (Philadelphia Gay Liberation Front-Newsletter, Aug. 9, 1970)

Shortly after Huey Newton issued his powerful statement of support for the gay and women’s liberation movements in The Black Panther newspaper on Aug. 21, 1970, the Young Lords Party formed an internal gay caucus. One of its first members was Latinx trans Stonewall combatant Sylvia Rivera.

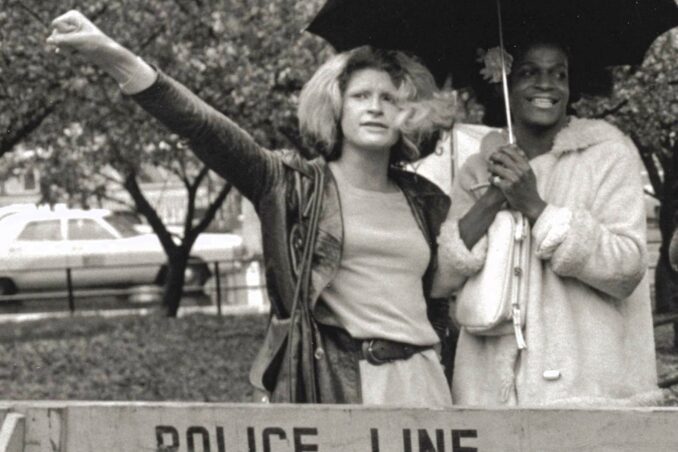

Sylvia Rivera (left) and Marsha P. Johnson, Stonewall combatants and trans liberation leaders in the 1980s, New York City. Credit: Diana Davies

Rivera described joining in autumn 1970: “It was just the respect they gave us as human beings. They gave us a lot of respect. It was a fabulous feeling for me to be myself — being part of the Young Lords as a drag queen — and my organization [STAR — Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries] being part of the Young Lords.” (Feinberg, “Transgender Warriors”)

The Young Lords Party held its own inquiry into the death of a Black gay prisoner — Raymond Lavon Moore — after he was found dead in November 1970 on the fourth floor of the Tombs prison in lower Manhattan. That was the floor where gay and trans prisoners were locked up.

Prison officials claimed Moore took his own life. But gay prisoner Richard Harris courageously came forward with his eyewitness account of the beatings Moore sustained from guards preceding his death.

The Young Lords charged that the administration had killed Moore. Gay liberation activists formed the Gay Community Prisoner Defense Committee after Moore’s death. On at least one occasion, Gay Liberation Front in New York provided bail money for two jailed Young Lords members.

Support for Panthers

Not all Black Panther Party leaders supported gay rights, and not all gay activists supported the Panthers. But many left-wing gay liberationists — Black, Latinx, Asian, Indigenous and white — worked hard to build and widen solidarity for the Panther Party.

The “Radical Caucus” at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations also won a resolution in support of the Black Panther Party; and when the conference leadership tried to overturn the measure, a wider vote sustained the resolution.

A GLF representative spoke at the huge May 1970 rally in New Haven organized to free Panther co-founder Bobby Seale.

The case of the Panther 21 drew demonstrative support from gay liberationists of all nationalities. The 21 were arrested in New York on April 2, 1969, in a pre-dawn police raid and charged with conspiracy to bomb the Botanical Gardens, department stores and other sites. They were finally acquitted of all charges on May 13, 1971, after 45 minutes of jury deliberation following what had been the longest political trial in the city’s history.

During the long trial, gay activists, including members of the Gay Liberation Front, had organized in support of the Panther defendants. The GLF Marxist study group — Red Butterfly — organized a gay liberationist contingent at a massive rally to “Free the Panther 21 and All Political Prisoners.” And the New York GLF donated $500 — quite a sum for activists in those days [when Village rents were about $70 a month] — to the Committee to Defend the Black Panthers.