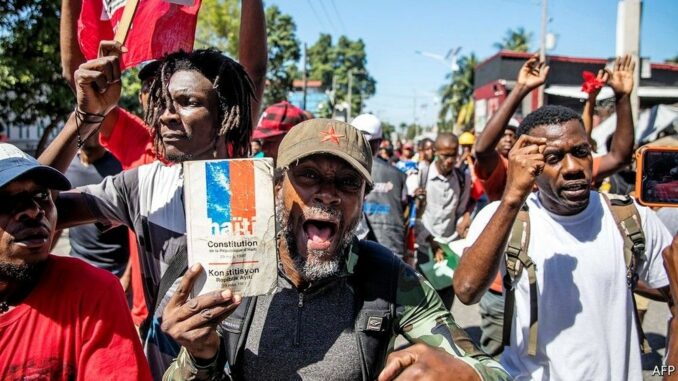

Haitians say: We want justice!

Tens of thousands of Haitians surged through the streets of Port-au-Prince and smaller cities Les Cayes, Jacmel and Carrefour March 29, demanding respect for the Constitution adopted 35 years ago March 29, 1987.

Protest coincides with the 35th anniversary of Haiti’s 1987 Constitution, following other protests and strikes in recent weeks.

While protests in Port-au-Prince were nonviolent, in Les Cayes protesters invaded the airport and burned a small airplane belonging to U.S. missionaries. They fought with police, who shot and killed one protester, and seriously injured others.

Besides demanding the Constitution be followed, placards in Port-au-Prince read “If you Ariel Henry don’t leave, we are going to die,” “Down with Ariel! Down with kidnapping! Down with high prices!” Henry is the acting prime minister without parliamentary approval.

Demonstrators protesting increasing violence at the Antoine Simon Des Cayes airport in Les Cayes, Haiti, March 29.

Since Jean-Bertrand Aristide received 67.5% of the vote Dec. 16, 1990, running against the U.S. candidate Marc Bazin, who received only 14.2%, the Haitian people have viewed voting and elections as part of their class struggle and part of their opposition to the oppressive system that exploits them. Elections are seen as a tool to oppose neocolonialists U.S. and France that use the local bourgeoisie to work their will.

The U.S. twice organized coups against Aristide after he was elected, because he had popular support and would have led Haiti in a progressive direction.

At times the manipulations and maneuvers, the coalitions and neocolonialist interventions over elections are complicated and hard to disentangle. But one thing is clear: Voting in Haiti often is not choosing the “lesser of two evils.”

How Haiti’s next presidential election will be conducted still has not been settled.

Current situation

Since previous Haitian president Jovenel Moïse, with firm U.S. support, chose not to organize elections and ruled by decree, no official in Haiti has an electoral mandate. Moïse was assassinated last July. De facto acting Prime Minister Ariel Henry, perhaps implicated in the assassination plot, runs the country because government officials take his direction without parliament getting in the way.

Lawlessness and criminal activity, including kidnappings, have spread throughout Haiti. According to police, kidnappings increased 58% over last year, with 225 cases already reported in 2022. Kidnapping criminal gangs have blocked road access to Port-au-Prince from Jacmel, Les Cayes and Jérémie, major cities in Haiti’s southwest.

A pastor conducting a televised service was kidnapped. There are anecdotal reports of people in police uniforms participating in kidnappings. The jet burned at the Les Cayes airport allowed the U.S. missionaries to overfly this blockade and bring in supplies without paying the gangs.

U.S. deportations of 20,000 Haitians caused considerable suffering. An additional 150,000 to 250,000 Haitians, still in Latin America without jobs and unable to send money home, are trying to get into the U.S. Their remittances made up nearly a third of Haiti’s GDP (gross domestic product). This is another hidden, but real, strain on Haiti’s economy.