Harriet Tubman, a woman called General Moses

Harriet Tubman was born on a Dorchester, Maryland, plantation sometime during March 1822 and died March 10, 1913, at her home in Auburn, New York. Workers World celebrates the 200th anniversary of her birth with this commentary, first posted Feb. 18, 2007, on Mumia Abu-Jamal’s “Radio Essays.” (tinyurl.com/4cdr5ev8)

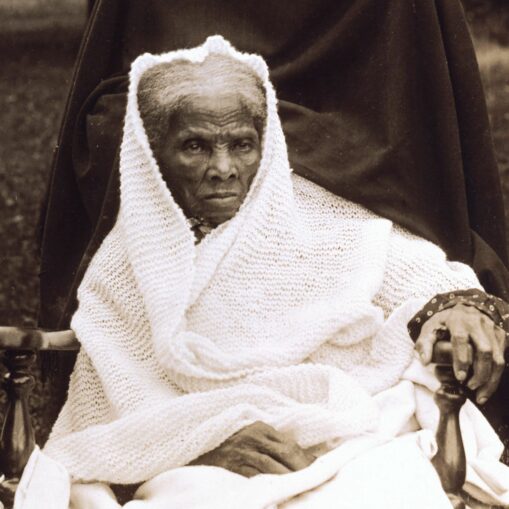

Harriet Tubman in 1911

She has been gone for almost a century; and still her name is on millions of lips, her memory sacred among those who love freedom.

Her parents named her Araminta, the daughter of Black slaves in the Tidewater area of Maryland, perhaps in 1820 (or 1821 — no one is sure).

As a baby, the slaves shortened her fancy name into the nickname, “Minty.”

History remembers her by her married name: Harriet Tubman, freedom fighter.

She began on the road to freedom as a child, for she wasn’t even 10 years old when she ran away from cruel slave owners, people who used naked violence against babies and children to force them to do their will.

Harriet was a tender five years old when she was forced to take care of a white baby, to keep house, to work day and night for others. She was all of seven years old when she got caught eating some sugar, food that only white people were allowed to eat. Threatened with a beating, the girl fled and, running so fast that her little legs gave out, she fell into a hog-slopping slough. Hunger forced her to return to the house of her “’mistress,” where she was promptly and viciously flogged by the “master.”

This child no doubt learned an important lesson by the violence, but doubtless it wasn’t what the slaveowning class wanted her to learn. They wanted to instill the seed of terror into the child, so that she never thought of running away again.

Instead, it appears she learned that if she ran, there would be no return.

She married a “free” man, John Tubman, who was free in name, and in law, but hardly in mind. When she talked about freedom, he shouted at her to stop it. “You take off, and I’ll tell the Master. I’ll tell the Master right quick,” he threatened.

As she looked at her husband, a feeling of disbelief washed over her, “You don’t mean that.”

But, in her guts, she knew. He did mean it.

Yet, she meant to be free. No doubt she learned another important lesson. Everybody can’t be trusted. She must be watchful, attentive and observant.

When the time came, she left, walking through thick forests, over rivers and over hills. She avoided open roads. She followed the North Star; and when she got to Pennsylvania (a so-called “free” state), she noted: “I had crossed the line. I was ‘free,’ but there was no one to welcome me to the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land; and my home, after all, was down in Maryland, because my father, my mother, my brothers, my sisters and friends were there. But I was free, and they should be free! I would make a home in the North and bring them there!”

She said it. She meant it. She did it.

She returned repeatedly to the Tidewater and carried folks off, with cleverness, courage and determination.

She returned to the plantation two years after her escape for John Tubman, but the “free Negro” had remarried, and thinking himself free, didn’t want to leave Maryland! Still, this wouldn’t deter her from her sacred mission: freedom.

She carried a pistol, and once, while leading some 25 captives North, came within a hair’s breadth of using it. One of the men, bone-tired, hungry and scared, decided that nothing was worth this scampering through the swamps. He refused to be persuaded to move on, until she moved close to him and aiming the weapon at his head, said, “Move or die.” He moved.

In several days they were in Canada.

Harriet knew that a returned slave would be tortured until he told all he knew, thus endangering all who wanted to be free. To her, it was freedom or death. That simple.

She would later say, of her upbringing and of slavery itself: “I grew up like a neglected weed — ignorant of liberty, having no experience of it. I was not happy or content. Every time I saw a white man, I was afraid of being carried away. I had two sisters carried away in a chain gang — one of them left two children. We were always uneasy. . . . I think slavery is the next thing to hell.”

Her raids into the prison-states of the South led to the freedom of literally hundreds of Black people — including her own aged parents, Harriet and Benjamin Ross.

It is thought her family originally came from the Ashanti people, a tribe which hails mostly from the West African coast. (The central region of Ashanti life would be modern-day Ghana.)

Her life, from beginning to end, was one of resistance and struggle in freedom’s cause. There may have been 15 to 19 raids led by her into the South to free Black captives. In these raids, she liberated between 300 to 500 people.

Recruited to aid the Northern forces during the U.S. Civil War, Tubman organized and led the Combahee River Raid in South Carolina, which netted some 800 slaves and caused thousands of dollars damage to Southern installations. She reported with glee the sight of so many people escaping bondage.

Tubman would later recall the scene: “I never saw such a scene. We laughed and laughed and laughed. Here you’d see a woman with a pail on her head, rice-a-smoking in it just as she’d taken it from the fire, young ones hanging on behind . . . . One woman brought two pigs, a white one and a black one; we took them all on board, named the white pig Beauregard (a Southern general) and the black one Jeff Davis (president of the Confederacy). Sometimes the women would come with twins hanging around their necks. It appears I never saw so many twins in my life. Bags on their shoulders, baskets on their heads and young ones lagging behind, all loaded.”

Harriet Tubman left this life in 1913, living into her 90s. Her name has come to mean Freedom Fighter. It is a holy name, high on the altar of freedom.

Sources: Butch Lee, “Jailbreak Out of History: The Re-Biography of Harriet Tubman,” (Brooklyn: Stoopsale Books, 2000) and Ann Petry, “Harriet Tubman, Conductor on the Underground Railroad,” (New York: Harper Collins, 1955).

Mumia Abu-Jamal © 2007