Fighting for voting rights and workers’ rights

WW commentary

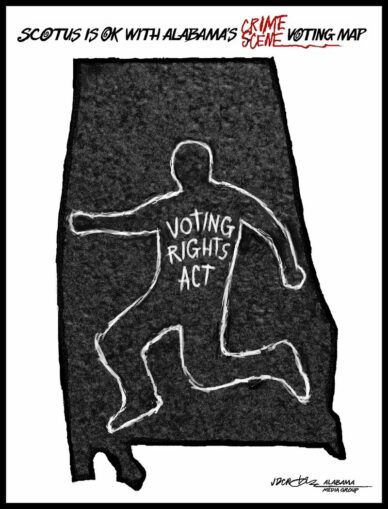

In an act of blatant racism, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a 5-4 ruling Feb. 7 that halted a lower court’s order to make Alabama redraw its gerrymandered Congressional districts and set up fair representation for the state’s Black voters. A federal appeals panel — made up of one Clinton-appointed judge and two Trump appointees — had upheld the lower court decision.

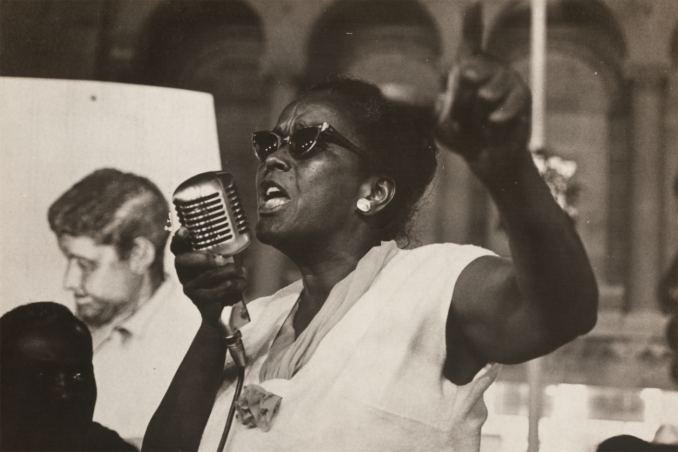

Ella Baker, a leader of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, led a challenge to white segregationist Mississippi Democrats at the 1964 National Democratic Convention.

The SCOTUS decision paused the lower court’s ruling for review at a later date — very conveniently not until after Alabama elections in May that will determine the fate of the state’s Republican legislators and governor!

Out-and-out legal racism

Alabama’s gerrymandered map included one majority Black district and six that are heavily white.

Voting rights advocates argued the state should have a second majority-Black district, or one close to a majority, because Alabama’s population is 27% Black. The Republican legislature’s map would give representation equivalent to only about 14% of the Black population. The map could have been redrawn easily with standard redistricting principles, such as keeping communities intact as much as possible.

The SCOTUS ruling is yet another bitter blow in a renewed attack on voting rights underway for the last 25 years. Reactionary state laws and judicial attacks have focused on eviscerating protections and undermining the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which was intended to ensure that state and local governments do not pass laws or policies denying U.S. citizens the equal right to vote based on race.

Passage of the Voting Rights Act was won during a time when fascist laws mandating segregation by race were still on the books and brutally enforced in many states. Denial of the right to vote to Black people was an integral tool of keeping killing injustice in place.

The Black Civil Rights Movement challenged this legalized racism and won historic victories, including the VRA, through the martyrdom of hundreds and the sacrifice of thousands of organizers and ordinary on-the-ground people.

But pushback by reactionary forces against this struggle for justice — sometimes through legislation, sometimes through white-supremacist terror — has never stopped.

In 2010 the county commissioners of Shelby County, Alabama, filed suit in federal court to declare Section 5 of the VRA unconstitutional. This section was crucial to VRA enforcement, as it required certain jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to submit for approval any proposed changes in voting procedures to the U.S. Department of Justice or to a federal district court in Washington to protect “minority voters.”

In other words, Section 5 was there to hold historically racist local and state governments accountable — absolutely necessary in places where Blacks had been evicted from their homes, shot down in the streets and lynched for asserting their right to vote.

But on June 25, 2013, the Supreme Court dumped this key VRA provision in its ruling, Shelby County v. Holder.

Party politics — or racist class maneuvers?

Currently in Southern states like Alabama, the Republican Party is almost uniformly made up of white people, and the Democratic Party of Black people and a minority of white people who support racial justice, women’s and LGBTQ2S+ issues, reform or abolition of prisons, disability justice, workers’ rights or environmental issues.

As a result of this split, gerrymandering can look like a matter of racist Republican Party politics, while the Democratic Party comes off as “liberal” on the right to vote. But until the late 1960s, Democrats were the party of rabid segregationists in the South.

The battle for voting rights is not Democrats vs. Republicans. It must be framed in the historical context of Black working people in the South — a people kidnapped to this country and enslaved, fighting for the right to actually be recognized as human, for the right to personal freedom and for the right to all the political freedoms accorded to white people in general, within a bourgeois capitalist democracy like the U.S.

The fight for voting rights

It is not a figure of speech to say the Black population freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had to “fight for democratic rights.”

The Southern white slavocracy, defeated militarily, was determined not to be subdued economically. After the Civil War and the passing of the 13th Amendment that formally emancipated all enslaved people, Southern white-majority governments of former enslaving states began to pass laws attempting to return freed people to de facto bondage. Beginning in Mississippi in 1865, these so-called “Black Codes” appeared to grant Black people certain legal rights for the first time, such as the right to marry. But in reality the Codes “were promulgated to control a newly fluid Black labor force.” (Encyclopedia of Southern Culture)

Then started the reign of “White Terror” — extralegal vigilante forces organized by the slavocracy to beat back the emerging social, economic and political independence of the freed Black population. This intimidation, occurring in every county, town and village and state of the old Confederacy, included the founding of the Ku Klux Klan.

For 10 years after the end of the Civil War, there was battle after battle in the South, as the African American population and some white allies tried to liberate the land. Every act toward freedom was a struggle. One witness recounted Black people in Mississippi marching to the voting polls “after the manner of soldiers, armed with clubs and sticks, some of them with old swords and pieces of scythe blades.” (James S. Allen, “Reconstruction: the Battle for Democracy 1865-1876”)

Control of state legislatures, local communities and public resources depended on these smaller battles. This was true then, in the battle over the destiny of local and state government in Alabama and the South — and it is true today.

The fight for economic justice

The greatest significance in these struggles lay in the fact that the battle of African Americans for their bourgeois democratic rights (like the right to vote, to testify in court, to form civil contracts such as marriage, to hold office) was completely, inextricably and openly linked to their fight for economic justice.

If they could not win redistribution of land, through outright occupation or through reparations legislation such as the “40 acres” grants proposed by abolitionists, then newly freed Black people would have no material basis for survival and no way to resist the seizure of their newly-won rights by a resurgent slavocracy.

Again, this connection between fighting for the vote and fighting for economic justice was true then, and it is true today.

In Alabama, if the Democrats were the party of segregation, Big Steel and “Big Mule” agriculture in the 20th century, then the Republicans have become the party of voter rights suppression, anti-unionization, Big Coal and Amazon in the 21st.

The recent SCOTUS decision must be seen in this context. Its significance is not just about limiting the right to vote. The ruling is meant to ensure the continued dominance of a Republican Party that will buttress Big Business. The ruling has wide implications for the South and the rest of the country, as the Republican Party continues to solidify its role as the bourgeois party of racist reaction, in contrast to the Democratic Party with its minimal, toothless gestures toward “democracy.”

The suppression of voting rights—aimed dead-on at Black voters in the South and spreading throughout the country—is a clear example of how capitalist “democracy” works to keep embattled, oppressed peoples from gaining any handhold on power within this unjust system. This includes worker power.

The right to vote — for a union

It’s no surprise that Alabama has been the site of two recent major defeats for Black voting rights. Control by a Republican conservative majority is necessary to ensure the state government’s favor to capitalist demands and requirements for investment in the state.

According to scholar James Cobb, Big Business has flourished in the South “because of the continuing willingness of its political leaders to serve up huge subsidies and the more than ample pool of relatively cheap, overwhelmingly nonunion labor. . . .” (“Globalization and the American South,” 2005)

In Alabama, there are now South Korean Hyundai auto plants, as well as Japanese Toyota and Honda, German Mercedes-Benz and Canadian New Flyer assembly lines. Meanwhile in domestic production, centibillionaire Jeff Bezos has his Blue Origin company building rockets in Huntsville, a huge Amazon distribution center located in Bessemer, and is opening more mammoth warehouses soon in the state.

A nonunionized workforce is necessary to maximize capitalist exploitation. And that means keeping racism active, Black people oppressed, white and Black workers divided and union organizing at a minimum.

But the Black workers of Alabama, and of the South, have a keen memory of the history of struggle for their freedom and for their rights. For many, knowledge comes directly to them through their families’ participation in the Freedom Struggle.

As Southern legislators now pass bill after bill designed to keep histories of injustice from being taught in the public school systems, Black and white coal miners have been united on strike for almost a year in Brookwood, Alabama, while a majority-Black, majority-woman workforce is organizing for a second union election at Amazon in Bessemer.

Now, in the rest of the U.S. as well as in Alabama, there has been a rising up of workers. A 21st century struggle is emerging — not in the courts or even in the streets — but in the workplace, where new rights are ready to be won.