Clyde Bellecourt: the Thunder Before the Storm

Hundreds gathered to honor the life of Clyde Bellecourt, White Earth Ojibwe, in Minneapolis, Jan. 13. Bellecourt, 85, was the last living founding member of the American Indian Movement and a lifelong civil-rights activist known worldwide. (Star Tribune, Jan. 13)

Clyde Bellecourt speaks at rally in Minneapolis, MN, Nov, 2, 2014

Bellecourt, whose Ojibwe name is Neegawnwaywidung, (the Thunder Before the Storm), was born and raised on the White Earth Indian Reservation. Both his parents had been kidnapped from their families and survived the boarding schools, of which he said, “it was an effort to strip us of our language, our culture and our traditional way of life.” (Indian Country Today, Jan. 12)

Bellecourt ran away from boarding school himself and was locked up for truancy at Red Wing Correctional Facility for juveniles; he later served time at St. Cloud and Stillwater state prisons for robbery. At Stillwater, he met Eddie Benton-Banai, Anishinaabe, who believed if Native people learned their history and their culture, that would build pride and take the community forward. Through their work there, many Native prisoners cut their time by half. Bellecourt left and began working as an engineer and a community activist.

During a 1968 community meeting in Minneapolis against police brutality, Bellecourt and others painted five cars red and deployed as the first AIM patrol to monitor police activity. A movement was born!

AIM quickly spread to inspire a generation of Native activists on reservations and inner cities across the country.

“Indian people had no legal rights centers, job training centers, community clinics, Native American studies programs or Indian child welfare statutes,” Bellecourt wrote in his memoir “The Thunder Before the Storm” (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2016). “There were no Indian casinos or Indian schools, no Indian preference housing. We were prohibited from practicing our spirituality. It was illegal to be in our country. The Movement changed all that.” (Star Tribune, Oct. 21, 2016)

Bellecourt joined with Black activists in 1970 to launch the Legal Rights Center, a community-owned law firm in Minneapolis, as an alternative to the Public Defender’s Office to provide high-quality representation for Native, Black and other people of color who were unable to obtain such services.

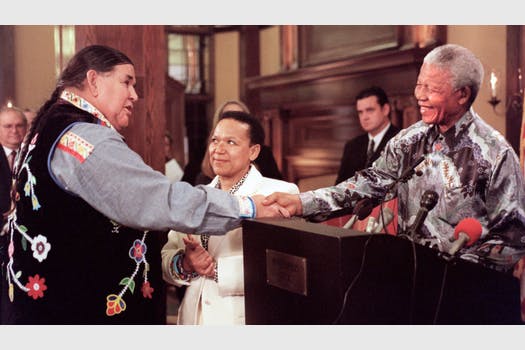

Clyde Bellecourt shakes hand of Nelson Mandela, Nov. 21, 2000.

The birth of AIM

AIM carried out a takeover of an abandoned Naval Air Station in Minneapolis in 1971 and organized a march to Washington, D.C., in 1972, called the Trail of Broken Treaties. The march, from the West Coast to Washington, D.C., demanded the U.S. honor the treaties, which are encoded as the law of the land according to the Constitution. AIM took over the Bureau of Indian Affairs building, forcing President Dick Nixon to agree to consider their demands. AIM then became a target of COINTELPRO, along with the Black Panther Party and other organizations.

In its most well-known action, AIM organized a 71-day occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1973, to protest corruption of Pine Ridge Reservation’s tribal government and charge the Bureau of Indian Affairs with injustices against Natives. The protest drew worldwide attention to Indigenous peoples’ struggles.

AIM went on to start health clinics, treatment centers, schools, a local job training center, a Native womens’ shelter, and a program to retrieve Native children from foster care. Along with other programs, AIM was granted control of the Little Earth Housing Project. Bellecourt often said people who heard about AIM wanted to talk only about the high-profile uprisings of the 1970s, but he was proud of building many organizations promoting community self-sufficiency.

“We made it clear that we were the landlords and caretakers of the country, and it was the end of the month, and the rent was due, in health, education and welfare,” Bellecourt said. “They didn’t get the land for nothing.” (Star Tribune, Feb. 19, 2019)

AIM became a national rallying cry for Indigenous youth, and their work with youth led to creation of specialized schools, college Native studies courses and departments that promoted pride in Native culture, ultimately a re-examination of the record of the settler-colonial history of the U.S. in tandem with the legacy of slavery.

“He had a very strong voice and presence,” said Kate Beane, leading Dakota historian and educator and director of the Minnesota Museum of American Art. “He fought so hard for Native American education, and his legacy is that young Native Americans can feel prideful for who they are as Indigenous students.” (Star Tribune, Jan. 11)

Bellecourt lived the AIM leadership saying of “anytime, anyplace, anywhere,” from organizing against the racist slur name of the Washington NFL team (finally dropped in 2020), to supporting the water protectors and land defenders against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock or Enbridge Line 3 in Hubbard County — Bellecourt was there.