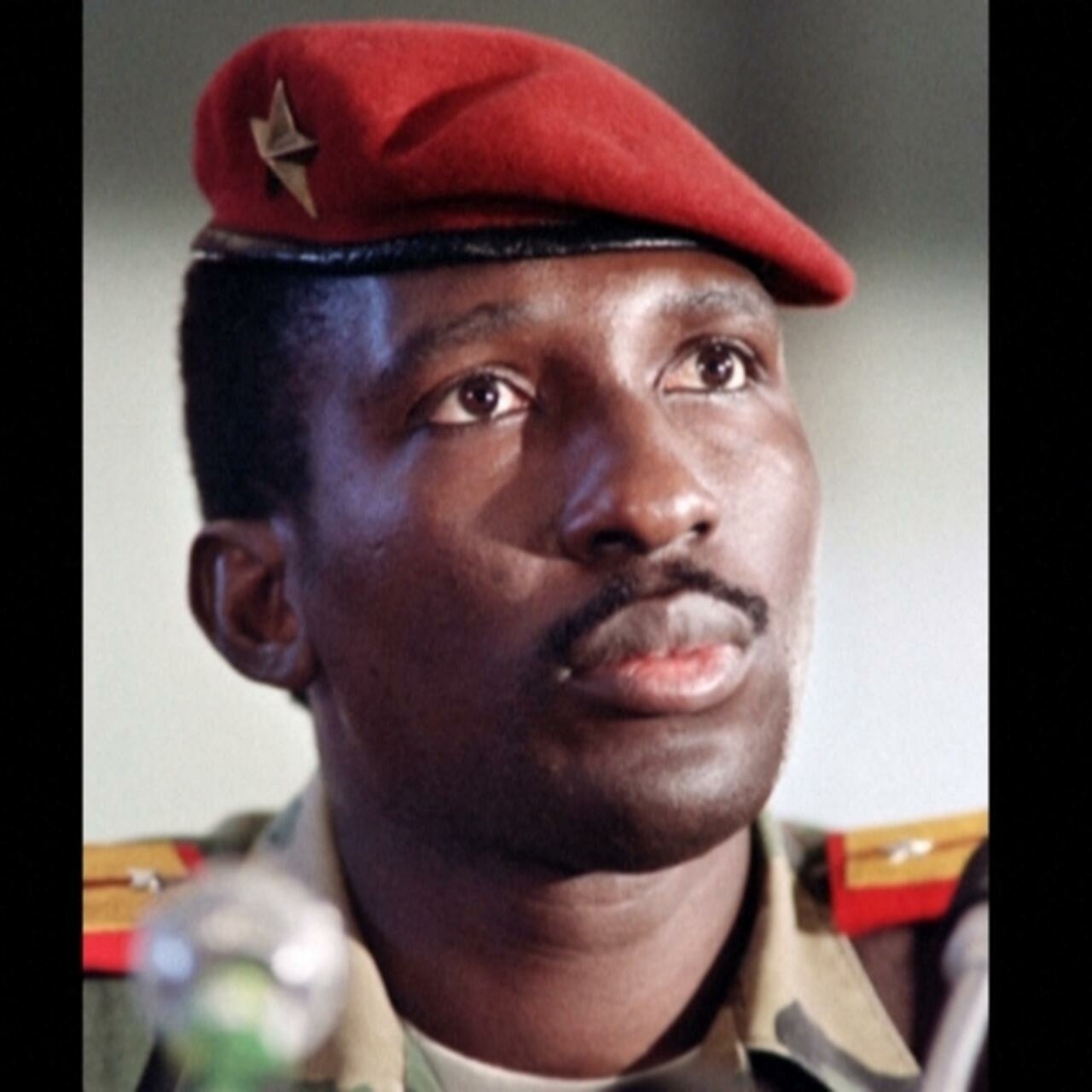

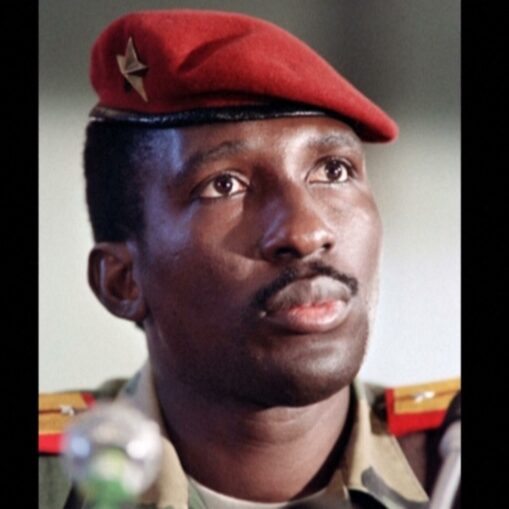

Thomas Sankara

Thomas Sankara

In April 2021 a military court in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, finally indicted Blaise Compaore in the murder of revolutionary Marxist-Leninist and former Burkinabe president Thomas Sankara. Sankara established a revolutionary government in Burkina Faso in August 1983.

In October 1987 Compaore oversaw a coup d’etat that resulted in the assassination of Sankara and 12 other Burkinabe officials. He proceeded to reverse Sankara’s policies and force Burkina Faso back to reliance on capitalist, colonialist entities, such as its colonizer France and the International Monetary Fund.

Compaore is now one of 14 people being tried on a variety of charges ranging from assassination to concealment of a corpse. Compaore has lived in the Ivory Coast since 2014, after he fled Burkina Faso when a popular uprising forced his resignation after a 27-year rule marked by unfair, rigged elections.

Reclaiming the revolutionary work of Sankara

The steps Compaore took to “rectify” Burkina Faso after Sankara’s assassination were supposedly done to “restore the shattered Burkinabe economy.”

When communist leaders die or are assassinated, a fierce propaganda campaign is undertaken immediately by imperialist powers, neocolonialist coup leaders and others to tarnish the reputation of the ousted leader, to delegitimize their work, to topple the revolutionary foundation on which they built and to send the masses back into the clutches of capitalism-imperialism. Such was the case of Blaise Compaore and his long attack on Thomas Sankara.

So what were the “disastrous” policies of Thomas Sankara? Did progress or reaction triumph with his ousting and assassination?

‘A new society’

In August 1983, Thomas Sankara and members of a left-wing armed forces faction, including Blaise Compaore, seized power from Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo, president of what was then known as Upper Volta. This came one year after Ouédraogo himself had seized power from Saye Zerbo and installed a right-wing government, which put Sankara into house arrest.

Immediately upon taking power, Sankara sought to bring about ecological, economic and social changes to the country of Upper Volta, which was quickly renamed Burkina Faso, or ‘Land of Incorruptible People.’

Sankara borrowed principles and structural ideas from socialist Cuba, such as the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. In Burkina Faso, these were revolutionary cells in every workplace, village and urban neighborhood to “organize the Voltaic [later Burkinabe] people as a whole and involve them in the revolutionary struggle.” (“Thomas Sankara Speaks: The Burkina Faso Revolution,” pp. 94-95)

Responsibilities for these groups consisted of political education of the Burkinabe masses, information against backward ideas and slanderous lies, organizing plans of action to support the revolution, upholding the line of the National Council for the Revolution (CNR) and practicing democratic centralism. This type of governing was a dramatic change from the previous feudal government of Upper Volta and ushered in what Sankara deemed “a new society.”

Women’s liberationAn early major change undertaken by Sankara related to the role of women in Burkina Faso’s government and the revolution overall. He emphasized: “The weight of age-old traditions in our society has relegated women to the rank of beasts of burden. Women suffer doubly from the scourges of neocolonial society. First, they experience the same suffering as men. Second, they are subjected to additional suffering by men.” (“Thomas Sankara Speaks,” pp. 102)

Sankara spoke of his own outdated views on the role of women, vowing to both change himself and plant a seed of change in every man in Burkina Faso, so that a woman would no longer be seen as biologically inferior or merely a sexual being, wife, mother or sister, but as a freedom fighter, a disciplined revolutionary and dedicated cadre.

Sankara showed that, using dialectical materialist thinking, the oppression of women is based in economic and social conditions of capitalism-imperialism, through the historical transition of different forms of society that gradually emphasized and normalized the oppression of women. “Women’s oppression,” Sankara said, “was a direct reflection of her economic oppression.” He emphasized that this truth can only be brought to consciousness through a dialectical process of understanding women’s place as an active social force in the revolution. [“Thomas Sankara Speaks,” pp. 341]

Under Sankara’s government, forced marriages and polygamy were outlawed, as was genital surgery on girls. The Women’s Union of Burkina was founded and ensured a swift and democratic mobilization of women cadres for liberation and defense of the revolution. Women were guaranteed positions in the CNR and were encouraged to work outside the home, helping to build the Burkina Faso revolution. This move was unprecedented for its time and cemented Sankara’s place as a fighter for women’s liberation that still persists today.

10 million trees

By the 1983 revolution, Burkina Faso had been in a period of drought for over 30 years. The country is part of the southern range of the Sahel, an ecotone south of the Sahara desert in northern Africa. By 1986, the desertification of the Sahel was advancing at 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) a year.

In Burkina Faso, the Burkinabe people combated this desertification with the 1983 rollout of the People’s Development Program. Under an initiative of Sankara and the CNR, people planted 10 million trees. A requirement of every family in the villages was that they must plant 100 trees per year, and 7,000 plant nurseries were created for widespread seed-planting.

When new housing and community spaces were built, these could be rented not for a price but for a promise the renter would plant the minimum number of trees in that location and tend to them as they grew. In instances of conviction for arson, one punishment was planting a certain number of trees.

Between 1984 and 1986, to reduce consumption of firewood from trees, 83,500 cookstoves were built by schoolchildren as school projects and by women in initiatives to support the revolution.

Vaccinations, water and the lives of children

Prior to the revolution, the Burkina Faso literacy rate was 12%, and school attendance of children was 6%. In two years under Sankara’s government, school attendance and the literacy rate both jumped to 22%.

Prerevolution, upwards of 50,000 children died annually from meningitis or measles. Sankara began a massive vaccination campaign that saw 2.5 million children between nine months and 14 years old vaccinated against measles, which can cause meningitis. The lives of tens of thousands of children were saved.

With the revolution, 5,000 pharmacies were built in more than 70% of the villages. Wells were drilled, ensuring clean drinking water to every district, including 20 that had not had any clean drinking water.

By 1984, one year after the revolution, infant mortality had dropped from 208 per 1,000 to 145.

Pan-Africanism

In the revolutionary government that Thomas Sankara created in Burkina Faso in August 1983, he emphasized both Marxism-Leninism and Pan-Africanism. In 1984, Sankara visited Ethiopia, Angola, Congo, Gabon, Mozambique and Madagascar. He proclaimed that his Burkinabe government recognized the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, and that the Organization of African Unity, a Pan-Africanist anti-colonialist organization, should not meet without the SADR.

Sankara sought to establish links between Burkina Faso and all African nations to form a Pan-African front against Western colonialism and neocolonialism, the latter of which is a final stage of capitalism-imperialism.

Sankara expressed his refusal to accept foreign aid, famously saying that “he who feeds you, controls you.” He recognized that any “foreign aid” rendered to Burkina Faso would contain the thinly veiled motive to overthrow the socialist government and establish a neocolonial power, whether through France or the U.S.

Sankara called on African nations to repudiate their foreign debt, saying that they had no obligation to pay it: “This debt has nothing to do with us. Which is why we cannot pay it. The debt is another form of neocolonialism, one in which the colonialists have transformed themselves into technical assistants. Actually, it would be more correct to say technical assassins.” (“Thomas Sankara Speaks,” pp. 373)

Sankara’s call for all African nations to repudiate this debt and unite in an all-African front against colonialism earned him the admiration of millions of nationally oppressed and working-class people and the ire of neo-colonialists and the capitalist class.

‘A people who are convinced, not conquered’

In one of his final speeches, on the fourth and final anniversary of socialist Burkina Faso, Sankara spoke to the 8 million people of the country on the urgent need for all Burkinabe to unite together and defend the Marxist-Leninist revolution and ideology.

During the last year of his government, left-opposition groups formed against Sankara, many of them Maoist in origin. These were opposed to Sankara’s plan to halt certain projects in order to rededicate the people to the task of political education and organization.

Sankara had proposed rehiring teachers and other workers, who had been dismissed following the 1983 revolution because of their anti-revolutionary views. These workers had been convinced of the successes of the revolution and had joined the ranks of the masses who supported it. The left-opposition groups did not believe in this shift, with even members of the CNR attacking Sankara for this decision.

Despite this opposition, Sankara spoke clearly that while Burkina Faso had accomplished much in four years, much more was needed. He projected this would involve a five-year plan continuing into the 1990s. He correctly theorized that the reactionary forces of neocolonialism and imperialism were growing and gaining traction, and the masses would have to be more vigilant than ever in resisting their attacks.

He criticized those who attacked the revolution and dismissed those who did not completely agree with the revolution, saying that they must be convinced, not suppressed. He stated: “The revolution does not look for shortcuts. It requires that we all march together, united in thought and in deed. This is why the revolutionary must be a perpetual teacher and a perpetual question mark. If the masses do not yet understand, it is our fault. We must take the time to explain and take the time to convince the masses so that we can act with them and in their interests.” (“Thomas Sankara Speaks,” pp. 399)

‘Disastrous’?

One can read the above profile of Thomas Sankara, and then read a criticism of his “disastrous” leadership, and still be confused or unsure. So here’s a summary:

Thomas Sankara put women in government and demanded Women’s Liberation be at the forefront of the revolution. He devised a plan that enabled the Burkinabe to beat back the creeping desertification of their land, an incredible feat to accomplish. His leadership led to the vaccination of over 2 million children, opened thousands of pharmacies and oversaw the literacy rate rising to historic highs.

Thomas Sankara opposed all Western imperialism and colonialism and believed that not only should the foreign debt placed on many African nations by western imperialism and colonialism be refused by the nations, but that it should be canceled altogether. He advanced planning for all African nations to work cooperatively for a liberated future free of capitalism and colonialism.

Thomas Sankara believed that if the working-class masses did not understand Marxism-Leninism, it was the fault of the Marxist-Leninists, himself included, for not doing enough to teach it. He emphasized that education must always be prioritized in order for the revolution to be defended and that those who did not understand were not to be condemned, but convinced.

Understanding that Marxism-Leninism guided Thomas Sankara’s revolutionary stance and work — and understanding the monumental work accomplished in Burkina Faso under Sankara’s socialist leadership — can we then say his leadership was disastrous? No.

Thomas Sankara’s leadership was revolutionary and necessary for the good of Burkina Faso and of humanity. His words and actions live on.

Thomas Sankara, despite his assassination, remains unconquered.

Thousands of people converged on Tufts University on March 26 to demand that U.S. Immigration…

Atlanta Sheikh Baba Bilal Sunni-Ali was a dedicated revolutionary, accomplished musician, political prisoner, beloved father…

Hundreds of militant protesters marched through Cleveland on March 22 to protest the latest genocide…

Women leaders from Venezuela and Nicaragua held an open discussion, complete with Q&A, at a…

by ResistNato&alpas The following is a copyedited version of the March 22, 2025, statement of…

In Seattle, 200 postal workers rallied and marched in the rain, “just like mail carriers…