Nicaragua, with free health care and education, challenges U.S. domination

Managua, Nicaragua

The writer was a member of a U.S. delegation that visited Nicaragua Oct. 3-10.

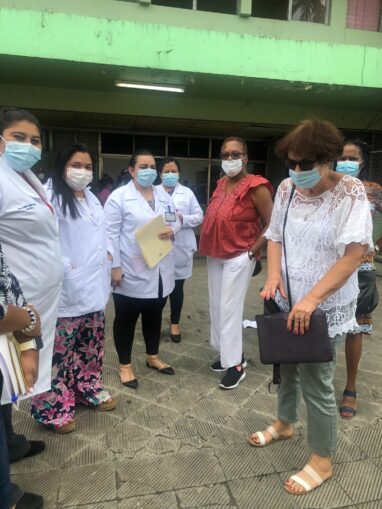

Outside of Óscar Danilo Rosales Hospital in Leon, Nicaragua with members of medical staff and U.S. delegation, Oct. 5. Rosales, a surgeon and Sandinista hero, was killed in 1967 by the U.S.-backed Somoza regime. (WW Photo: Sara Flounders)

The reason Nicaragua is labeled an “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security of the U.S.” – a military corporate superpower – became abundantly clear to a delegation visiting the country Oct. 3 to 10. The delegation was organized by the Alliance for Global Justice/Nica Network.

Nicaragua, a small developing country of 6.6 million people, lives in sharp contrast to its neighboring countries – Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. U.S. power dominates them, and over half a million people have fled the extreme violence, chaos and desperate economic conditions of these homelands. At the U.S. border, those migrants meet racist raids, round-ups and deportation, although it is U.S. policies that forced them to flee.

By contrast, comparatively few people have left Nicaragua.

Nicaragua’s stability challenges U.S. domination

The recent delegation met with Nicaraguan doctors, medical staff, community organizers, teachers, disaster specialists and financial planners to learn about the impact of the country’s Human Development Plan, which supports its stability.

In stark contrast to other Central American countries which have privatized health care for profit, Nicaragua has established community-based, free public health care, as well as free education for all. Unlike its neighbors, Nicaragua has instituted a major focus on disaster planning – essential in a region prone to hurricanes, volcanoes, earthquakes and tsunamis.

The AFGJ delegation was able to measure the difference between Nicaragua today and the state of the country in 2007, when 16 years of U.S.-backed neoliberal policies left every social program sold off to private investors.

Retaking Nicaragua for the people

Back in 1979, the Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional) had defeated the U.S.-backed Somoza dictatorship. When the FSLN came into governmental power, the U.S. sent armed mercenaries to wage relentless war in Nicaragua. The FSLN government was defeated when a U.S.-backed reactionary slate of candidates was elected in 1990.

In 2007, the Sandinista FSLN Coalition returned to political office in a general election, with a sharply different approach. They have attempted to revitalize the programs of the Sandinista Revolution and the years of struggle against U.S. domination.

Since the Sandinistas’ return there have been stunning gains in maternal and infant survival, life expectancy and even in building new infrastructure of roads, electrification and sanitation. Women hold close to half the elected seats in the national legislature and are a majority of the doctors, health professionals and planners.

These concrete successes are what Washington and corporate power in the U.S. find so threatening. The example of Nicaragua’s independence is too dangerous to U.S. control over the region.

Human Development Plan

There is much national pride and enthusiasm in Nicaragua about the results of the Human Development Plan. Everyone the AFGJ delegation met with was emphatic about the difference made through mobilizing the population in a holistic approach and the positive impact on how people feel about themselves and how they look out for their neighbors.

The plan has vastly increased public investment in basic health services, education, potable water and environmental sanitation, especially in long-ignored rural areas. Today 66 percent of Nicaragua’s budget goes to health and education – a huge investment for any country.

More than a century of U.S. corporate exploitation and direct U.S. military occupation, U.S.-backed military dictatorships and U.S.-supported contra wars, followed by the most recent U.S.-supported government of the elites, had left Nicaragua impoverished and underdeveloped when the Sandinistas returned in 2007.

The country’s Caribbean coast on the east – where most Nicaraguans of African descent live – was left almost completely impoverished, with development restricted to the Spanish-speaking urban areas of the Pacific coast. Some 90 percent of medical services went to less than 10 percent of the population – the ruling elite and a prosperous middle class. Millions of people had no access to health care.

Now, however, infant and maternal mortality is less than a third of the 2007 level. At that time, fewer than 50 percent of the population had access to electricity. The FSLN government proudly proclaims that 98 percent of homes have access to electricity. The country is self-sustaining in basic food needs. In 2007, 48 percent of the country’s population lived below the poverty line. Now poverty is 18 percent. Education, including medical school, is free.

Building infrastructure

Roads are essential, both to transport goods and to raise the level of access to health care and education. Today Nicaragua boasts of the best paved roads in Central America. Large parts of the country once totally isolated are now part of national life.

Digging wells and constant water tests have brought potable water to 95 percent of urban areas and more than half of rural communities. While modern sewage and sanitation have more than doubled in urban areas, they are still a challenge in rural areas.

What impressed the AFGJ delegation in briefings by government planners was the honest assessment of what still needs to be accomplished to raise living standards for the whole population. But gains confirm that the current government’s investment in social welfare programs is already having a big impact.

Community-based, not-for-profit health care

The Human Development Plan emphasizes community-based preventive and primary medical care. There is a strong focus on confronting centuries of inequality on the underdeveloped Caribbean coast and in rural areas that previously had never seen a doctor.

The health coverage network has been widened, with 192 health centers and 1,233 health posts that provide the first line of neighborhood care for immunization, high blood pressure and diabetes control. There are 178 “mother houses” where women can safely deliver babies, receive nursing advice and have complicated pregnancies carefully monitored.

The training of doctors, nurses, medical technicians and health administrators is a high priority. Medical workers are unionized state employees.

Deepening health care means building and outfitting hospitals, testing facilities, mobile medical clinics and other support infrastructure. Nineteen new hospitals have been built since 2007 and six more are planned.

There is a great deal of attention to small community development projects, such as installation of wells, roof repair, flood preparation and evacuation plans against disasters, and workshops in health and wellness.

Free health care includes much not covered by Medicare in the U.S., such as dental care, hearing aids, glasses and pharmaceuticals. Traditional medicinal herbs, physical therapy, massage and nutrition are being integrated into medical care. Recreation, sports and culture are considered part of health care.

Volunteer health brigades

One effective innovation is the Health Brigade Volunteers – community health advocates mostly chosen originally from the Sandinista Youth Organization to serve in rural regions. Now all neighborhoods have trained Brigadistas.

For instance, the city of Leon, population 200,000, has 3,000 brigade volunteers who go door-to-door checking in with neighbors to give personalized attention and health education.

Organized years before the COVID pandemic hit, the Brigadista network was used to support extensive vaccine programs for flu, pneumonia, measles and other children’s diseases; to combat dengue, zika and malaria; to conduct nutritional surveys, health censuses and health education; and to help people get to appointments, receive medications and get follow-up care.

Health care and COVID

When COVID hit, the Brigadista social infrastructure gave instant health support to a population already vaccinated for many diseases and well educated on basic health and sanitation measures.

Nicaragua had an intense discussion on the difficulty of completely shutting down an economy that is still based on small farmers, small producers, craftspeople, local markets and community-based economic development. Some 41 percent of Nicaraguans live in rural areas, and 31 percent of the labor force is employed in agriculture.

Instead of a shutdown, health professionals and Brigadistas went house-to-house, educating families on how to protect themselves from the virus. There was an emphasis on testing and isolation.

The impact of community education was seen by the AFGJ delegation wherever it traveled. Everywhere they went Nicaraguans were wearing masks – in restaurants, streets, government buildings, schools, neighborhood cafes. As people entered buildings or met in groups, everyone sprayed their hands with sanitizer.

Nicaragua was hit by a slow COVID vaccine rollout, due to the unequal distribution of vaccines globally. In mid-September, larger donations of vaccines began to arrive through the international COVAX system. A fully vaccinated population before January 2022 is the goal.

But vaccines could have arrived earlier: the U.S. donated vaccines to every country in Central America except Nicaragua. By early September, the U.S. had thrown away more than 15 million doses of COVID vaccines – more than enough to have vaccinated every Nicaraguan twice. The use of punitive “vaccine diplomacy” and the U.S. denial of humanitarian pandemic aid highlights the intention of the U.S. ruling class to use any effort to overthrow the Sandinista government.

Nicaragua faces intense U.S. pressure and many challenges based on centuries of colonial and imperialist oppression. But there is a great deal of creative energy focused on improvements that will impact the largest number of people and address historic inequality with revolutionary determination.