A turning point in American corrections

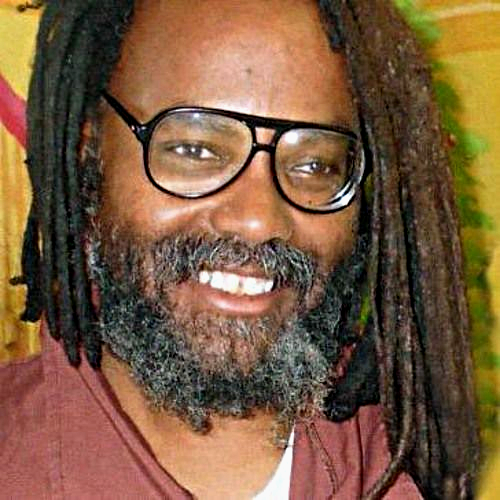

The following lightly edited commentary by Mumia Abu-Jamal aired as part of the “50 Years of Resistance: Black August & Attica” live broadcast, hosted by the Prisoners Solidarity Committee of Workers World Party, Sept. 2.

In my mind, Attica was a turning point in American — and I use the term loosely — corrections. It was like, what road will be taken? And the state, through Rockefeller, the governor of New York, chose the road of mass repression.

The media largely supported his efforts. They maligned and lied against these men using really classic racism and fear. They charged that these men killed the men that the state killed. I think it was 39 people including 10 prison employees.

It took generations to have courts say, in a civil action, that it was not so. But it wasn’t true that day, that night, that month, that week. Attica became a hallmark of American corrections and really the American way of repression, instead of a tribune hour of liberation. What those men asked for was no retaliation, no charges and then specific changes to the prison. And they knew that the state, through prison officials, would kill them.

They said, send us to another country. We would rather go to another country than endure this kind of repression. They had press conferences; they wrote letters; they told this to the esteemed public officials and journalists who they met with. I don’t think people took them seriously, until it was too late. So what could have been a liberation moment, became one of the most repressive moments in American history. This was the naked face of the repressive state, punishing people who wanted to be free.

Think about it from this context. A decade after Attica, a U.S. president demanded that the president of a neighboring socialist state [Cuba] kick out his prisoners and free them, and let them come to the United States. What’s the difference in principle here? Thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of people fled Cuba. They called it the Mariel boatlift.

Many of those people ended up in the U.S. prison system. And some remain there today. They are mostly in Terre Haute, Ind. Because even though they’ve served their sentences, America was like, you can stay in America. But you ain’t going out. That’s the reality.

My point is that why was what an American president did applicable, but what African American and Puerto Rican prisoners said absurd? It’s the same thing. Now they might not have found a great life in the countries they wanted to go to. But you know, hopefully they would have found freedom, something they did not have in the United States. They may have lived to an old old age, instead of being slaughtered by state troopers. And they wouldn’t have found the kind of class and race denial that meant their executions in Attica.

Those are the things I think about when I think about Attica. It really was a turning point. There was a live option that could have gone another way, but for the political forces in New York state and in the United States. This just didn’t come from the governor, so much as through the governor. Rockefeller had political ambitions as a Republican official. And the United States didn’t want the embarrassment of people demanding to be freed from the United States prisons. So they kind of killed two birds with one stone.