Life expectancy drop exposes racism, class bias

The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) released “provisional life expectancy estimates” for the U.S. based on provisional mortality data for January through December 2020. The statistics show that overall U.S. life expectancy was reduced by a year and six months during this time period.

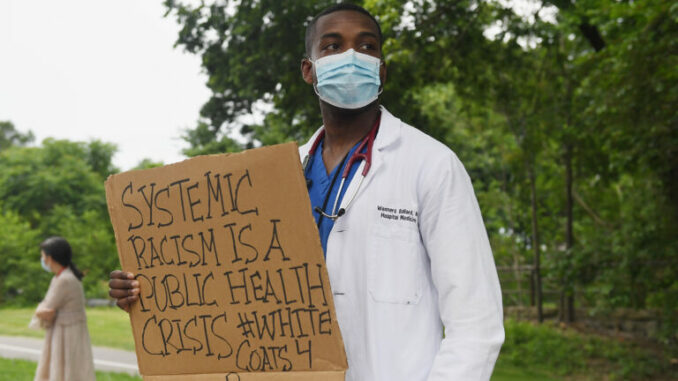

Health care worker links racism in health care to police murder of George Floyd in 2020.

The disturbing report indicates the steepest decline of life expectancy since World War II. The conclusions from the report are: “U.S. life expectancy at birth for 2020, based on nearly final data, was 77.3 years, the lowest it has been since 2003. Male life expectancy (74.5) also declined to a level not seen since 2003, while female life expectancy (80.2) returned to the lowest level since 2005.”

Two major factors for this statistical drop are the pandemic and the opioid crisis. The pandemic has caused the deaths of over 600,000 people in the U.S. Although the death rate has slowed due to millions getting vaccinations, the current spread of the Delta variant is causing another drastic rise in hospitalizations. At the same time, businesses and public places have eased their restrictions on mask wearing and social distancing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that the rise in drug overdose deaths, attributed to 14% of the cases in the 18-month decline in life expectancy, was due to isolation and despair caused mainly by the pandemic. There was a 30% increase in these deaths from 72,151 in 2019 to a staggering 93,331 in 2020, according to a separate CDC report released on July 14.

Impact of racism and class

The NCHS reports the impact of this decline in life expectancy upon communities of color, stating, “The Hispanic [Latinx] population experienced the largest decline in life expectancy between 2019 and 2020, from 81.8 to 78.8 years, reaching a level lower than what it was in 2006 (80.3 years), the first year for which life expectancy estimates by Hispanic origin were produced.

“The non-Hispanic Black population experienced the second largest decline in life expectancy (from 74.7 to 71.8) and was the lowest estimate seen since 2000 for the Black population (regardless of [Latinx] origin). Life expectancy for the non-Hispanic white population declined from 78.8 to 77.6 years, a level last observed in 2002 for the white population (regardless of [Latinx] origin).”

The figures show that life expectancy for people of color, especially Black and Latinx, has dropped by three years. Black people already had a lower life expectancy before the pandemic hit, compared to Latinx and white people.

The pandemic has had a devastating impact on essential workers — especially in the areas of health care, mass transit, restaurants and grocery stores and other industries that require people to work outside of home. These workers tend to be people of color.

Also Black and Brown people are more susceptible to the virus when living in overcrowded housing with multigenerational family members or traveling in overcrowded buses and subways for work. Many migrant workers are not eligible to receive health care. Due to their understandable fear of being detained or deported due to their undocumented status, many forego vaccinations.

Jon Zelner, an epidemiologist at the University of Michigan, stated in a New York Times interview that “the federal government could have protected workers from risky work situations by providing income subsidies allowing them to stay home and could have ensured adequate protective equipment to workers in nursing homes and long-term care facilities.” (Dec. 9)

Some 2020 studies have shown that while the deaths of people of color and whites are equal when it comes to the virus, 60% to 70% of Black and Latinx people were more likely to be infected than whites. In a Veterans Administration study in New Orleans, “Black patients accounted for 76.9% of those hospitalized with COVID-19, although they made up just 31% of the health system’s population.” (Dec. 9)

Lack of health care for generations

The U.S. is the richest and largest imperialist country, but according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in the area of public health, compared to its peer nations it ranked a poor 27th out of 37 in 2018. (Washington Post, July 26) The decline in life expectancy for poor and working people must be viewed within the general social context of this ranking.

However, communities of color suffer the added burden of health care disparities that did not occur overnight but have been around as long as poverty has existed.

In a Feb. 8 WW article “Reparations, health care and the pandemic,” this writer noted, “The inequality of death during the pandemic reflects the fact that lack of adequate health care for Black people is not an isolated occurrence but has been a generational inequality.”

On June 3, a study was released by University of Michigan Medicine researchers on health disparities between Black and white patients tied to white supremacy within class society. “From inadequate access to fresh food and clean water, to screening in early stages of disease or the inability to rent an apartment because of discriminatory housing practices, these long-standing systemic inequities for some Black Americans can have long-lasting effects on health.” (healthblog.uofmhealth.org)

Some of Michigan Health’s findings included: Black people have higher rates of obesity, heart disease and hypertension; and Black men have a 2.5 times higher rate of prostate cancer mortality. The lack of doctors of color means lack of medical visits. Nearly half of all Black, Latinx and Indigenous women had a lapse of insurance coverage between preconception and after delivering their babies, compared to approximately a fourth of white women.

There has been a huge jump in colon cancer among young African Americans due to a gap in early diagnosis. Black people are more likely than white people to develop dementia as they age, due to the impact of high blood pressure on cognition, memory and executive function.

The National Poll on Healthy Aging indicated food insecurity disparities — by age, health status, race, ethnicity and education — have been potentially worsened by the pandemic. “Access to nutritious food and health status are closely linked, yet this poll reveals major disparities in that access,” says Preeti Malani, M.D., the poll’s director. “Even as we focus on preventing the spread of coronavirus, we must also ensure that older adults can get food that aligns with any health conditions they have, so we don’t exacerbate diabetes, hypertension, digestive disorders and other conditions further.” (healthyagingpoll.org)

These findings smash the racist myth that Black and other people of color are genetically prone to contract the coronavirus, rather than suffering from substandard living conditions and health care they receive, which is not isolated but institutionalized. This is why reparations in the area of the right to health care must be a clarion call supported by all workers in solidarity with the most oppressed facing genocidal treatment.