Step toward unionization, student-athletes win historic ruling

The National Collegiate Athletic Association waived its archaic rules June 30 to allow student-athletes to earn money off their popularity and visibility for the first time in its 115-year history.

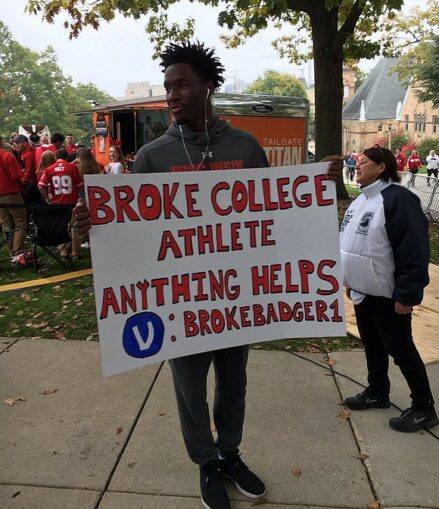

University of Wisconsin basketball player, Nigel Hayes, Madison, October 2016.

College athletes can now negotiate endorsement deals, profit off their social media accounts, sell autographs and otherwise make money from their names, images and likenesses, potentially directing millions of dollars into the pockets of these athletes every year. And they will have the right of legal representation in making these deals.

This is a historic ruling, since college athletes have been shamelessly superexploited for decades by athletic programs, booster clubs and college administrations for their ability to perform superb athletic feats before packed arenas and fields in a multitude of sporting events. The athletes have had no direct compensation or benefits like other workers.

The NCAA waiver comes just hours before a number of state legislatures were scheduled to potentially pass laws that would institute athletes’ compensation in colleges and universities statewide. The NCAA’s reversal came a day before a July 1 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court which found the association guilty of violating an antitrust law. The Court ruled in favor of women and men athletes demanding to be paid, and the Court’s ruling left the NCAA vulnerable to future lawsuits on behalf of athletes demanding the right to earn money.

But there is no guarantee that every athlete will be able to take advantage of the new options being granted. Much depends on which sport they participate in and whether they play for Division I, II or III teams — with Division I being the most popular and by far the most profitable.

NCAA functions like a corporation

The NCAA — like every other capitalist entity — is based on making profit. The NCAA receives over $1 billion in revenue annually from two main sources: The first is the Division I men’s basketball annual championship tournament known as “March Madness,” which generates over $867 million in television and marketing. The second is from other championship sales that reap close to $180 million — not even counting football bowl games.

In the NCAA, 64% of basketball players and 57% of football players are African American — who overwhelmingly come from poor and working-class families. It is not surprising that Black athletes tend to be more pro-union than white players.

A main role of the NCAA is to grant scholarships for indigent players whose families cannot afford the exorbitant tuition of prestigious colleges and universities that are overwhelmingly white.

NCAA coaches make an average annual salary of over $800,000, with the highest salary going to the University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban, who makes over $9 million. Mark Emmert, president of the NCAA, makes a base salary of $2.7 million without perks.

Compare these salaries to student-athletes who on average receive only $20,000 in aid for a school year. And food stipends are included in those grants. The athlete’s package can be so inadequate for overall school costs that — to make their money stretch — they can go without adequate amounts of food on a daily basis.

The NCAA ruling is significant to student-athletes for another reason — because the NCAA is in essence their boss. The ruling will help pave the way for the athletes to be organized like other workers.

In 2014, some Northwestern University football players formed the College Athletes Players Association to fight for their team’s right to organize a union. The athletes questioned why shirts with their likeness could be sold for $50 but when groceries are donated to them if they are hungry, they are the ones punished by being suspended from games or even being expelled from school. The NCAA prohibits student-athletes from having independent health insurance. But when athletes get injured while playing, they can end up with permanent knee or brain damage, two of the most prominent injuries.

The National Labor Relations Board sided with the Northwestern administration in not recognizing the athletes as “university employees.” The Northwestern football team eventually voted down the idea of a union in 2015, but the struggle is far from over at that school and others.

The Black Lives Matter struggle — which intensified in summer 2020 over the police murder of George Floyd — has helped to empower student-athletes to take to the streets to fight for social justice, which also encompasses economic justice.

Workers are demanding a living wage, better working conditions and benefits from corporate behemoths like Amazon, Whole Foods, Walmart and others. As other workers move forward to get their rights at the bargaining table, the student-athlete workers will not be far behind.