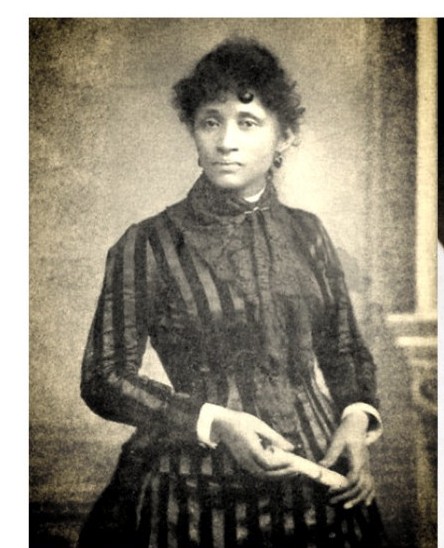

Lucy Gonzalez Parsons, an original founder when May Day launched in 1886, was born into slavery in the early 1850s on a Virginia plantation. She, her mother and others were able to escape and move to Texas. There she met her future spouse, Albert Parsons, a former Confederate soldier who helped register newly freed people to vote during Reconstruction. This action made him a target of the KKK who threatened to lynch him.

Brenda Stokely, union and women’s activist, speaks in front of Parsons banner at May Day rally, New York City. WW-photo G. Dunkel

Lucy and Albert were forced to leave Texas due to the miscegenation laws that legally outlawed mixed race marriages. They eventually moved to Chicago in 1873 where great labor struggles were taking place in the factories to demand an eight-hour day. Without union protection, the industrial workers, many of them poor immigrants from Europe, were forced to toil 10- to 16-hour days under horrendous working conditions.

Both Lucy and Albert became not only union organizers but also developed radical anarchist and anti-capitalist ideas. After Albert lost his printing job due to his political beliefs, Lucy opened a dress shop in her home to support him and their two children and hosted meetings for the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU).

On May 4, 1886, following a workers’ rally in Haymarket Square in Chicago, the police threw a bomb in the crowd, killing eight people and one of their own. Albert and seven other union organizers were targeted and framed for killing the officer. Four of them, including Albert, were hanged in the Square in 1887, forever becoming known as the Haymarket Martyrs. May Day was officially declared as International Workers Day in 1889 at an international socialist conference.

Lucy Parsons championed political rights as well as workers’ rights. For instance, she joined the worldwide campaign to stop the executions of two Italian immigrant union organizers, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, who were framed for murder in 1920. They were executed in 1927.

Lucy fought for the freedom of the Scottsboro Brothers, nine young Black men falsely accused of raping two white women in 1930 in Alabama. A worldwide campaign led by socialists and communists eventually exonerated them.

Lucy was a fighter until her death at the age of 91 on March 7, 1942, in a fire in her home. Suspected of setting the blaze, the Chicago police confiscated her precious books and writings that never saw the light of day again. Parsons was proud of being declared by the Chicago police as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters.”

Lucy Parsons was a militant and defiant anti-capitalist anarchist and a socialist, who wanted to empower the workers through revolution.

Lucy and Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, a coal miner organizer, were the first two women to join the Industrial Workers of the World. The union welcomed all workers, regardless of nationality, religion, gender or skill, into its ranks. Lucy organized campaigns against hunger and for unemployed councils on behalf of the IWW.

Some of Lucy’s most notable quotes from speeches include:

The spirit of Lucy Parsons continues to live in every revolutionary who abhors all forms of exploitation, oppression and inequality, who fights to abolish every ugly feature of capitalism and who fights for a socialist future for the liberation of all humanity. Lucy Parsons, ¡presente!

The epic struggle of the Palestinian people against the full weight of U.S. imperialism and…

The following report comes from the Bronx Anti-War Coalition organizers on a protest held in…

In the Canadian federal elections held on April 28, the Liberals won with 169 seats…

The following is Part 2 of a talk given by the author to a meeting…

Boston Students, professors and workers are confronting the Trump administration’s fascist crackdown at universities across…

Philadelphia Within days of Swarthmore students reviving a pro-Palestinian encampment on April 30, police arrested…