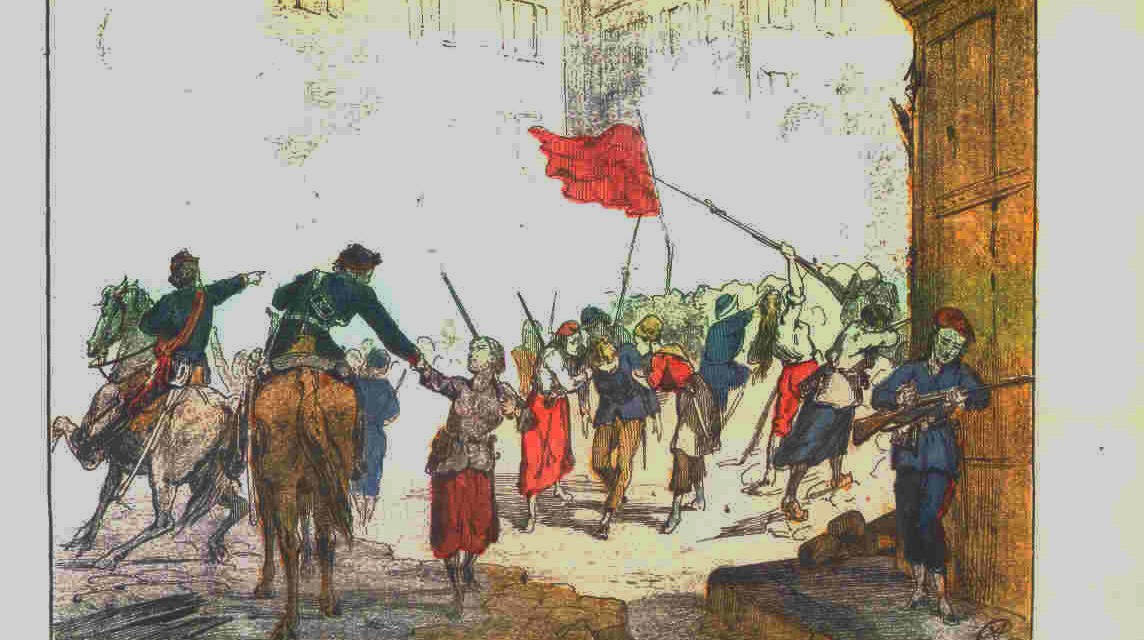

Women defending a barricade during the Commune

An uprising in Paris on March 18, 1871, toward the end of the Franco-Prussian War, burst open the structure of 19th-century European capitalist society. The 72-day social explosion in what would become the capital of the French Empire became the iconic blueprint for workers’ revolution.

Lessons of the Paris Commune, established 46 years earlier, laid the groundwork for the 1917 Russian Revolution, an event that dominated 20th-century class-struggle history.

After the 1789 French revolution executed and deposed the French monarchy, opening the road to political power for the capitalist class, France often set the pace for social conflict and social change in Europe. Uprisings took place in 1830 and 1848 that kept advancing the demands of the working class and city poor. The ruling capitalists used the army and police to crush these uprisings.

Marxists, anarchists and utopian socialists – who aimed to eliminate exploitation and create a society of equals – needed to answer the following question: Can an oppressed and exploited class seize power and run society?

The Paris Commune was the first event in European history that answered this question.

Women defending a barricade during the Commune

Setting the scene for the Commune was the disastrous war that Louis Napoleon (nephew of the first Napoleon and emperor of capitalist France from 1852-70) had begun against Prussia in the summer of 1870. By September, the Prussian army had taken prisoner 200,000 French troops and officers, including the emperor himself.

Political parties representing French capitalists deposed the emperor and set up a French republic. To consolidate their rule, they had to surrender to the Prussians.

The workers and poor of Paris, however, set up a National Guard that was more like a popular militia, refusing to surrender Paris to the Prussian army. The National Guard also began to defend the interests of the Parisian workers against the capitalists. By March of 1871 the conflict between the pro-capitalist National Assembly and the various revolutionary workers’ organizations of Paris, concentrated in the National Guard, had reached a boiling point.

The pot boils over

On March 18, the bourgeois (capitalist) assembly ordered 40,000 troops from what was left of the regular national army to seize the 300 cannons held by the National Guard in the hills of Paris, known as Montmartre. The operation aimed to provoke a battle with workers that would lead to the mass arrests of working-class leaders.

According to the revolutionary anarchist Louise Michel, at 8 a.m., the people in Montmartre, and especially the women, begin to fraternize with the troops of the regular army. At first, there was mutual fear. Then recognition. Soon there was solidarity.

Michel wrote: “The Butte of Montmartre was bathed in the first light of day, through which things were glimpsed as if they were hidden behind a thin veil of water. Gradually, the crowd increased. The other districts of Paris, hearing of the events taking place on the Butte of Montmartre, came to our assistance.

“The women of Paris covered the cannon with their bodies. When their officers ordered the soldiers to fire, the troops refused.” (Nic Maclellan, “Rebel Lives – Louise Michel”)

The troops then arrested their commanding officers. By that evening, some of these generals, who in 1848 had massacred the workers, had been executed.

Before midnight, the uprising had seized the National Guard headquarters, the central police headquarters and Paris City Hall. The rebels held most of the city.

Military mutiny gave birth to workers’ power

At dawn on that day, the central committee of the National Guard had set out merely to defend themselves from a military coup. By midnight they had, de facto, seized power.

This was Day 1 of the 72 days the Paris Commune existed – the democratic rule of the poor, led by the working class.

This uprising of Parisian workers was the essential prologue to the European revolutions of the twentieth century. It was the first revolution in a European capitalist society where the wage workers — the working class or modern proletariat, those who live by selling their labor power — succeeded in setting up their own government and their own state.

The Commune could exercise its power only within the city of Paris, the largest city and largest working-class center in the centralized capitalist state of France. But Versailles, where the French king had his palace before 1789, was just 10 miles away. Commune rule arose in some of the other major cities, like Lyon and Marseille, but could not sustain itself outside Paris.

And conversely, without support from the provinces, the Paris Commune was unable to control the destiny of France. Nevertheless, the historical lessons from this first workers’ revolution allowed revolutionary leaders elsewhere to prepare to carry out revolution in the next century.

The theoretical leader of the International Workers Organization, Karl Marx — who with Friedrich Engels had written the “Communist Manifesto” in 1847 — saw in the Paris Commune the first historical experience of how the working class could overthrow the capitalist ruling class and begin to run society in the interest of all the oppressed classes.

The living experience of the Commune showed that it was impossible for the working class and oppressed sectors of the population to simply win over Parliament and thereby start building a new social system. The old government, bureaucracy and armed forces were tied by innumerable strings to the old ruling class. Only by destroying this old state and building a new one, bound to the working class, could society be changed.

By the end of the day on March 18, 1871, most of the 50,000 rank-and-file troops of France’s regular army who had been in Paris had either changed their allegiance to the National Guard, deserted or been withdrawn from the city, while most of the French soldiers outside Paris were prisoners of the Prussians.

This meant that within Paris, the National Guard was both the political body directing the Commune and the armed force keeping order in the city. The National Guard constituted the new state power, which defended the unemployed, the workers, and the small producers and shopkeepers, all of whom saw the Commune as their government – a type of popular assembly, or what in Russia was called a council or soviet.

Marx, Lenin analyzed lessons of the Commune

Marx wrote of this in his pamphlet, “The Civil War in France,” published in 1871. Marx’s pamphlet became the basis for key chapters of the pamphlet “State and Revolution,” which the revolutionary communist leader V.I. Lenin wrote in the summer of 1917 on the eve of the Russian Revolution, an event which was to shape 20th-century history.

Lenin’s pamphlet provides a clear explanation of why it was necessary to smash the old state, which enforced capitalist rule, and replace it with a new state based on the rule of the working class. Only then could one change society.

For anyone seriously interested in a revolution that frees the downtrodden and oppressed, these two works are indispensable. And they are based on the living experience of the Paris Commune.

The Commune lasted only 72 days, but they were great days, during which laws were passed protecting the workers, poor and women and establishing a popular democracy.

The French ruling class government made what any French patriot would have to consider a “treasonous” deal with the Prussian generals. It ceded to the Prussians the province of Alsace-Lorraine. The Prussians, in return, released the French prisoners of war – soldiers whom the bourgeois government used to drown the Commune in blood.

These troops had been held as prisoners far from Paris, far from the revolutionary Parisian workers. They came mostly from rural areas and remained brainwashed by the lies of the rulers, who had moved their government from Paris to Versailles in 1862. In May, these troops obeyed their officers. They slaughtered the Communards who dared to defend Paris, including many of the women fighters of The Women’s Union, who were the most resolute defenders of the Commune.

Thirty-six years later, the workers of Russia seized state power in that country, using as a blueprint the experiences of the Paris Commune.

Catalinotto is author of “Turn the Guns Around: Mutinies, Soldier Revolts and Revolutions,” which contains a chapter on the Paris Commune. The works by Marx and Lenin mentioned in the article are available free online.

Hamas issued the following statement on April 24, 2025, published on Resistance News Network. The…

By D. Musa Springer This statement is from Hood Communist editor and organizer D. Musa…

Portland, Oregon On April 12 — following protests in Seattle and elsewhere in support of…

This statement was recently issued by over 30 groups. On Friday, March 28, Dr. Helyeh…

When Donald Trump announced massive tariffs on foreign imports April 2, Wall Street investors saw…

The century-long struggle to abolish the death penalty in the U.S. has been making significant…