A transgender formerly incarcerated activist speaks out

Lisa Strawn is a transgender woman who spent more than 35 years in California prisons due to that state’s draconian “Three Strikes” law. At the age of 19, she was locked up for petty offenses like prostitution, and on her third “strike,” Lisa was sentenced to 50-to-life for burglary. She has been incarcerated in California State Prison, Corcoran; the California Medical Facility at Vacaville and San Quentin State Prison. While inside, she was an activist and organizer on behalf of the LGBTQ+ incarcerated community. After contracting COVID inside San Quentin during the peak of the pandemic there, she was finally released to the community July 14, 2020 — still with COVID. She has continued her advocacy for her siblings inside. This is part 1 of a two-part interview conducted with Strawn on Dec. 30, 2020, by Judy Greenspan, a member of the Prisoners Solidarity Committee of Workers World Party.

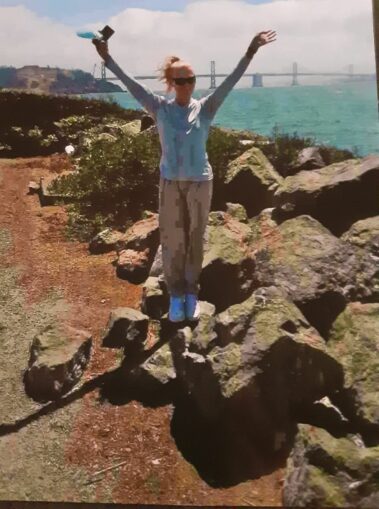

Lisa Strawn

Judy Greenspan: Lisa, what was it like for transgender prisoners when you first got locked up?

Lisa Strawn: I pretty much have been incarcerated my entire life since the age of 19. I started transitioning at 19. I started out at a level three prison, then I went to a level four, then a level three, then level two. And for me personally, being at a level four, there was so much more respect there from staff and the other incarcerated people (at Corcoran) than any of the other prisons including San Quentin.

Right before I had got to Corcoran, and that was in 1998, the staff were betting money on the inmates, the gladiator fights. And all those investigations were coming down, and I got there at the very end of it. So I think that really changed the spectrum of how they were treating people because, for the most part, we didn’t have any problems.

Up until 2005, we weren’t allowed to have hormones, and then it became a federal law, because this girl actually sued the Department of Corrections. And because she won the lawsuit, then they had to start giving us the hormone. They had to. I was at Corcoran.

JG: How were you treated by the prison guards after Corcoran?

LS: It was a struggle at CMF because the staff, they were so transphobic, homophobic. And I can remember many times when I literally had to call them out and embarrass them in front of their own people. There was a tour one day, and I could hear this sergeant say, “Oh, no, that’s a guy.” And I immediately stopped, and I let him have it.

And then it was just a huge scene. Then the watch commander was calling me on the phone: “Lisa, oh, he wants to talk to you, he wants to apologize.” And I was like, fuck him. I don’t want to talk to him. And then when I did meet him, I cussed him out. I said, “How dare you disrespect me like that in front of people who don’t even know nothing about me?” And I went on and on. He actually tried to talk to me in the hallway, and I walked away from it.

I got write-ups all the time. I mean, I had gotten a write-up right before I left on CMF Vacaville to go to San Quentin, because the officer said I wouldn’t get on the wall. Then I started doing paperwork about, well, I’m a woman, I shouldn’t be in a man’s prison, and I want to go to a women’s prison. And then there was the issue: “Well, if you want to stay here, you have to move to a dorm.” So I stood right in the hallway. And it was with a captain. And I looked at him, and I said, “Look at me. I’m wearing a bra, panties, makeup. My name is Lisa. It’s not Thomas. It’s Lisa. So do you really think that you’re going to put me in a dorm with child molesters and rapists?” And he just looked at me and says, “I’ll be back.”

And towards the end, it got really ugly because I became so political. Anything that I didn’t like, I was calling Sacramento, the ombudsman and other people and bitching. And so they booted me out of the prison. And it was actually the best thing they could do.

JG: When did you get involved in LGBTQ+ activism from the inside?

LS: I stayed at CMF for 10 years. And that’s when I really started doing a lot of navigating and being involved with the trans community, the LGBT community. We had two support groups. And then I put a third group in the prison. We had a transgender-only group. I was elected as the first transgender person on the Inmate Advisory Council. I started an LGBT group.

San Quentin, the day I got there . . . I was already the kind of person that was so involved with so many people on the outside in many organizations. And I was just like, okay, I have to come here, and I have to do amazing things too. And there was so much of a phobia. The guys, I mean, they were rude. They were just freaking rude. You know, make smartass comments, and I’m so not that one. And I just immediately got into journalism school . . . and I just really got involved. I navigated everything. And then I helped put the transgender support group in the prison and LGBTQ group.

JG: Tell me about the first Transgender Day of Remembrance that you organized at San Quentin.

LS: My thing was like promoting the rights of the LGBTQ community. And having the Transgender Day of Remembrance . . . that had never happened at that prison. Ever. It’ll never happen again. They still say that that was the biggest event that they’ve ever had. Because this bitch brought a senator inside that prison. Nobody else had done that.

But Transgender Day of Remembrance, it wasn’t just about the trans people who have been killed. I wanted to make sure that San Quentin got it right. So I had asked straight guys, “Do you guys want to be a part of this?” Nobody turned me down. I sent out personal invitations to so many people. And there was so many people who responded, they couldn’t let everybody in. We had 18 acts that performed in three hours. I was able to say for the first time San Quentin got it right . . . Not only do we now have groups for everybody, every gender, every race, religion, now we did it. And it was the best day.

Lisa Strawn