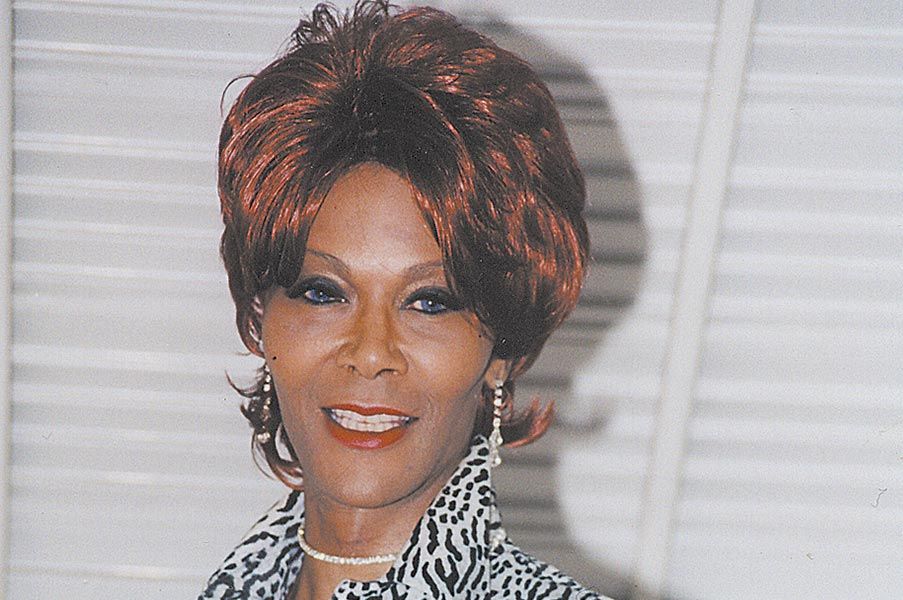

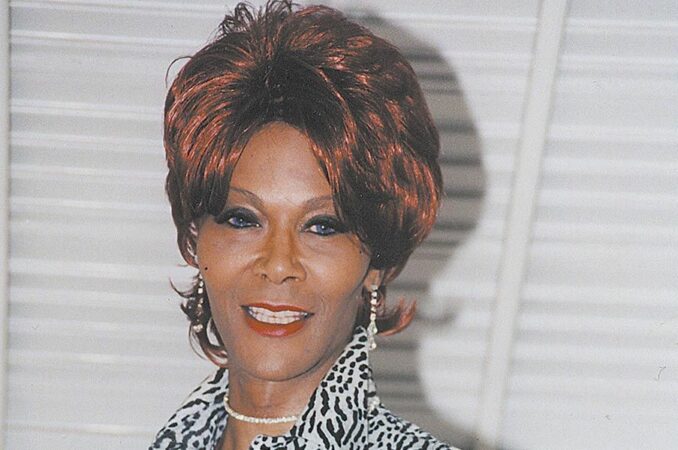

Nizah Morris

The article below was originally published on Dec. 9, 2014, at www.bgdblog.org. It has been slightly edited. Since that time, according to the Philadelphia Police Department, police lost the records of Nizah’s case. In 2018, transgender activist and lawyer Julie Chovanes argued in front of Common Pleas Judge Edward Wright using Pennsylvania’s Right to Know Law. Instead of issuing a decision from the bench, the judge gave a single sentence response: “This court affirms the decision of the District Attorney’s Office of Open Records” – which denied access to the records.

In February 2018, Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner said that the Morris case was not an open criminal investigation. Yet in 2019, a former District Attorney staffer claimed it was an open investigation. An important fact to remember is that Elizabeth Skala DiDonato was with Nizah Morris when she was attacked, according to her own words. Chovanes has pursued the coverup and continues to fight for Nizah.

At 207 Juniper Street, in the City of Brotherly Love, stood a bar called the Key West Bar and Grille. It had its own rich history, having been Philadelphia’s only integrated gay bar. But there, 12 years ago, lives were irrevocably changed. On any given night, there are thousands of drunk people in bars in that city. We are often reminded, however, that what are normal occurrences for the general public are “crimes” for trans people of color. Crimes that make us targets of police and police violence. Trans women of color are stopped, harassed, assaulted and murdered by police with impunity. The conversation about police violence must include us because our bodies, too, lay dead at their hands.

Nizah Morris

On Dec. 22, 2002, a black trans woman named Nizah Morris was drunk at Key West. Officers Elizabeth Skala-DiDonato, Thomas Berry, and Kenneth Novak were dispatched to the scene after a 911 call was placed by concerned friends. Skala-DiDonato offered Ms. Morris a courtesy ride to her home, and Berry accompanied them. Then, according to the police, Nizah sobered up and left the vehicle at 3:25 a.m.

Two minutes later, she was found bleeding and unconscious in the middle of the street. Berry was again dispatched to her location, where he declared a crime had not taken place, covering her face while she was still alive. Had she been taken to a hospital as soon as she was found, she more than likely would have lived. Instead, she was left on the scene for 40 minutes. She was taken to the hospital at 4:13 a.m. and died at 8:30 p.m. on Christmas Eve from a wound that could only have come from the butt of a gun.

While police say they do not know who or what killed her, the answer is obvious. The officers involved in her final moments, Skala-DiDonato, Berry, and Novak — the third officer sent to Key West who never accounted for his whereabouts between 3:13 a.m. and 3:25 a.m. — could more than likely have been her murderers. Nizah Morris’s death highlighted the immeasurable social and emotional distance between the trans community and the Philadelphia Police Department.

Police target transgender people of color

All over the U.S., police and transgender people are often at odds, the result of decades of policing that did not stop crimes, but enforced the unwritten laws of patriarchy and ensured social conformity. Black and/or Latinx transgender people often find ourselves the targets of increased police hostility because of white supremacist, transphobic policing being distinctly opposed to our continued existence.

In Philadelphia, trans women of color are often profiled as sex workers, drug addicts, or just plain criminals. Some of us are sex workers and/or drug addicts, the end result of being targeted for discrimination by the same oppressive system that profiles us. It doesn’t matter whether or not you’re actually doing something illegal, though, because being transgender (resisting patriarchy’s desire for our lives) is essentially illegal.

There used to be a competition among the officers of the Philadelphia Police Department. Precincts and individual officers would compete to see how many transgender women they could arrest or stop in one night. Did they ever stop this cruelty? I don’t know, but they adopted new standards and policies that would on paper give the impression that transgender people are respected by the PPD. Those new policies came about as the result of a laundry list of complaints of assault, sexual violence, and unrelenting insults during arrests which the transgender community presented to the PPD.

Cops harass writer

Sometimes what minor privileges we may have as individuals save us from the full depth of police violence. And sometimes they don’t. Despite being a trans woman of color from a lower economic class, I was able to attend a relatively inexpensive university in Philadelphia. I was standing at the corner of Broad and Diamond streets, walking home after visiting a friend, when two cops in an unmarked car and two more in a police cruiser pulled up and started catcalling and mocking me. They were asking for sexual favors, propositioning me, assuming I was a sex worker only because I’m transgender (I was, but they didn’t know that).

It wasn’t until they noticed that I had my school’s lanyard with my school ID card on it that they became silent and their demeanor changed. They sped off as soon as they got the chance. I didn’t think about it much when it happened, I was shaken up over it, but I realized that my school ID conferred upon me the illusion of class privilege. I still had the privilege that came with being a college student and that was my saving grace that night. I had other run-ins with the police where I wasn’t so lucky, but that incident stood out to me.

What many people don’t realize is that the police brutality the trans community faces is directly tied to other forms of discrimination we face. Some trans women of color are thrown out of their homes — even as children — and have to support themselves by attempting to get a job. Discrimination against transgender people in the workplace causes us to be unemployed or underemployed, so we have to turn to sex work. As sex workers, we get mistreated by clients and the police.

Police violence against sex workers, and those presumed to be sex workers, goes unpunished and uninvestigated because sex workers are seen as expendable by clients and worthy of destruction by the state. It’s a vicious cycle that is worsened by the constant threat of police violence towards anyone who is transgender or gender non-conforming.

Need for solidarity

There are thousands of us on any given day in any city, who are harassed and abused by police. It’s why, even when we’re the victims of crime, we don’t ask for help. We’re often the ones who end up arrested, injured, or emotionally traumatized, while even in the process of asking for their help. There have been times in Philadelphia when cisgender people got into fights with us. Like anyone else, we respond by defending ourselves, but what happens when we do? We’re often the ones carted away.

We must expand the conversation surrounding police brutality to include trans women who have been victimized or murdered by police. People like Nizah Morris, who was murdered for what white cistender people do every day in this country with nary a peep from the police, can’t fight for themselves. We must take up the fight for them, for our sisters who have been harassed, but survived, and ultimately for ourselves, because the next time it happens, it may be us.

Raposo is a Portuguese Marxist analyst, editor of the web magazine jornalmudardevida.net, where this article…

By Alireza Salehi The following commentary first appeared on the Iranian-based Press TV at tinyurl.com/53hdhskk.…

This is Part Two of a series based on a talk given at a national…

Educators for Palestine released the following news release on July 19, 2025. Washington, D.C. Educators…

On July 17, a court in France ordered the release of Georges Abdallah, a Lebanese…

The following are highlights from a speech given by Yemen’s Ansarallah Commander Sayyed Abdul-Malik Badr…