Breaking through the walls of isolation:

What is the Prisoners Solidarity Committee?

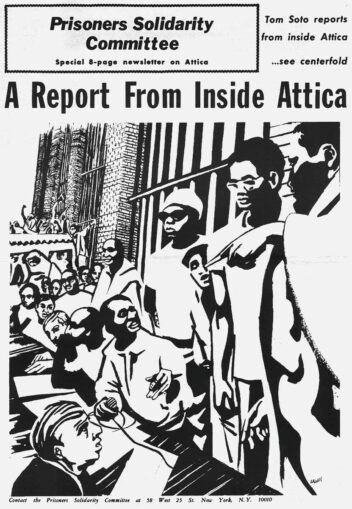

This slightly edited statement first appeared in the Sept. 17, 1971, WW as part of a special eight-page Prisoners Solidarity Committee insert, “A Report from Inside Attica,” in tribute to the Attica Prison uprising that occurred Sept. 9-13. This justified rebellion resulted in the massacre of over 40 prisoners by the storm troopers made up of the National Guard and state police of billionaire New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. Updated language has been added in brackets.

Once in a very great while, a rich man goes to prison. Maybe he is taking a six-month rap for a company that defrauded the people out of millions; when he gets out after his brief stretch, he’s set for life. And even while he’s in, every little comfort is provided for him, so that the time passes as pleasantly as possible.

Most of all, he is never really isolated, never forgotten. His lawyers visit him constantly, the guards treat him like a “gentleman,” and he is able to conduct his business affairs from prison.

Prisons weren’t made for people like this. The fact that a handful of them may be in a few federal institutions is largely an accident.

But the prisons are full, overflowing, exploding with poor, oppressed men, women [and gender-oppressed] people for whom prisons have meant the end — of life, of happiness, of friends and family. The first stretch becomes a stigma that dooms a young person to life behind bars. The prisoner never sees a lawyer, is prevented from defending himself, herself [and themselves], is estranged from his, her [or their] family just out of the sheer impossibility of visits to isolated prisons, and can look forward to desperation and disappointment when and if he, her [and they] ever hits the streets again.

For thousands of prisoners, especially the large percentage of Black, [Brown, Indigenous] and other oppressed people routed into the prisons from birth, these conditions have become unbearable. The terrible isolation imposed by the racist authorities has been broken again and again in the only way left to human beings who have been literally sealed in their own tombs: by open rebellion. These rebellions are specifically directed at the numberless injustices that read like a description of the Chamber of Horrors; but they are also something more.

The Prisoners Solidarity Committee is another absolutely indispensable product of this new spirit; it was formed less than a year ago [1970], when prisoners at Auburn, N.Y., wrote to organizations on the outside for help. Youth Against War & Fascism responded, and soon helped form the Prisoners Solidarity Committee. The committee has expanded to many cities since then and includes relatives of prisoners and released prisoners themselves.

When the news of the PSC reached the jails, it released a dammed-up flood of letters from brothers, sisters [and others] telling of the indignities, the brutality, the pain that is a daily part of prison life. But these letters all told something else. They were not pathetic appeals from beaten people; they rang with hope and strength and willingness to struggle. Moreover, the writers were thrilled that they were finally breaking out of their isolation, that people outside were listening and working with them.

The PSC published some of these letters in the pamphlet, “Prisoners Call Out: Freedom!”

The PSC raised some money with this pamphlet and social affairs, and rented a bus so that prisoners’ relatives could get to Auburn and visit them. For many of them, it was the first visit in years.

Building outside support

When the Auburn Six had several court hearings, the PSC got sizable demonstrations of support, even in blizzard conditions. More and more, the PSC became a vehicle whereby the prisoners themselves could speak to the people outside, could generalize their struggle, fuse their grievances and their hopes in the main current of rebellion that is rising in the country as a whole.

Thus it was a small wonder that when the heroic Attica prisoners met with a small group of observers during the rebellion, it was the PSC delegate, Tom Soto, who they most wanted to see. It was to him that they entrusted the greatest number of messages, for their loved ones and for the movement as a whole.

The PSC, on hearing of the rebellion, had immediately mobilized all its strength: It sent a delegation to Attica, arranged transportation for relatives and organized many demonstrations throughout New York state and in several major cities elsewhere. The prisoners knew that what they had to say would be heard on the outside.

At the most difficult moment, when ruling-class hysteria against the prisoners reached its height, the PSC announced from inside Attica that it unconditionally supported the prisoners’ demands. A further bond of love and trust was forged in those tense hours.

The isolation of the prisoners has been permanently shattered. Even the highest concrete wall, the darkest cell, the cruelest solitary “hole” can no longer hold the terror it once had, for 1,500 men at Attica have looked the worst in the face.