Larry Kramer, 1935-2020: An appreciation

I joined ACT-UP/NY soon after it formed, in the spring of 1987. Thirty-three years later, I still have vivid memories of the weekly meetings, which crackled with the electric energy of hundreds of angry people jammed into the first-floor meeting room in the LGBTQ Center in Manhattan.

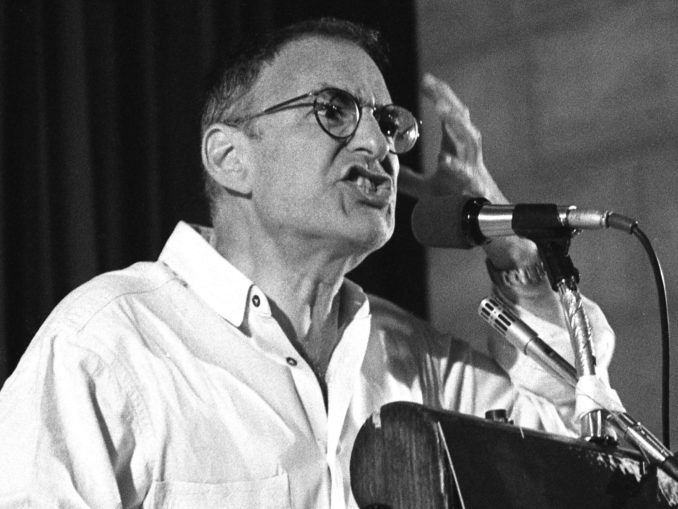

Larry Kramer

Many, probably most, had not been political activists before the AIDS crisis erupted. Now, as they orated, debated, strategized in that rundown old building on West 13th Street, they were creating a new movement, one that would make history and save lives. The task was enormous: to force the government, the ruling class, the medical establishment, the pharmaceutical industry to take real action to combat AIDS.

Tens of thousands were dying. Most were gay men and people of color. By 1987 the AIDS epidemic had been raging in these communities for years. The poorest, those with least access to medical care, were falling fastest. People were attending funerals, scratching names out of address books, trying to go on, to stay alive, with no hope of support or aid from any official source.

There were no effective treatments. There was no nationally coordinated public health effort to educate people about methods to prevent the spread of HIV. The president, Ronald Reagan, had never once spoken the word AIDS in public.

Meanwhile, anti-gay and racist violence was on the rise as reactionary forces whipped up fear and scapegoating campaigns.

This was the juncture when Larry Kramer stepped up and started the movement that would change everything.

Movements are made up of many people. Mass struggle is just that, a mass undertaking, and no one individual can accomplish everything. Still, leadership is decisive. And Larry Kramer was the leader we needed at the height of the AIDS crisis.

A few years earlier, as AIDS emerged as a deadly threat, Larry had been one of the founders of Gay Men’s Health Crisis. GMHC developed into a community service organization — vital, but not, Larry saw, sufficient. Something else was needed: a fight. A real, bare-knuckles, no-holds-barred fight had to be waged.

And so Larry Kramer, along with a few others, founded the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power.

It quickly developed and grew. Taking lessons from the Civil Rights Movement, the anti-war movement and of course the LGBTQ2+ movement, the young organizers who soon assumed leadership fashioned ACT UP into a street-fighting powerhouse.

ACT UP/NY’s first big action took place March 24, 1987. Hundreds poured onto lower Broadway in the early morning hours, targeting big business as the culprit for AIDS-based discrimination and the failure to develop and fund affordable AIDS treatment drugs.

The call to action proclaimed: “No More Business As Usual!” The goal: to shut down Wall Street.

We did just that. I was one of over 100 people arrested at the Wall Street action that morning. While cops dragged us off, hundreds more stayed, chanting the newly minted and now famous ACT UP slogan: “Act up! Fight back! Fight AIDS!”

In the months and years following, the AIDS activist movement would carry out many militant actions. They barricaded and sat in at pharmaceutical company headquarters. They crashed medical conferences and corporate board meetings. They disrupted reactionary religious events. They demanded attention, and action, and eventually they won real change.

Rage at oppression

So who was Larry Kramer? He was first and foremost a gay man. His bitter, painful experience of gay oppression drove everything he did. His rage, his furious, passionate rage at heterosexism, homophobia, LGBTQ2+ oppression was endless and profound, and it helped give rise to a great social movement.

He was an artist, a brilliant novelist and playwright, though, as Tony Kushner noted in a May 29 New York Times article, Kramer “sacrificed for the sake of his unceasing activism some of what he might have accomplished artistically.”

Larry was a Jewish child of the Depression. Later in life he was comfortable financially. He was never a revolutionary. But he always considered himself an outsider, an “other” in this society that he excoriated in his work, literary and political. He was a radical, and a true militant.

In ACT UP meetings I knew Larry only as an angry speaker, up in the front of that first-floor room at the center. I usually sat near the back, which his fiery energy easily reached. Friends tell of a different Larry up close and personal, a sweet, kind, loving soul.

I got to witness that sweet side a few years before he died. After not seeing Larry in person for decades, I ran into him at a deli one afternoon in the Village. I knew he’d weathered several major illnesses; he seemed bent and frail. I said hi and introduced myself as someone who’d been in ACT UP in the early years. He perked up, straightening his spine, giving me the widest, warmest smile, and reached in for a hug. For some reason we both got a little teary-eyed. We chatted a bit, then said goodbye.