Texas health care workers report from inside the pandemic

The following are lightly edited testimonies about the health care system response to the coronavirus COVID-19 from several workers who currently have jobs in Central Texas or have spent their lives working there.

EMT in Austin, Texas

The response from Central Texas hospitals, nursing homes and ambulance services has so far been what I expected from profit-based medicine. Precautions are not being taken with patients unless they have a verified case of COVID-19. In order for a case to be verified, a patient must pass a strict series of questions and symptom presentation before testing is even considered. People who test positive for the [regular] influenza but have persistent coughs are not placed on precautions. The assumption is that if you have one [illness], then you can’t have the other.

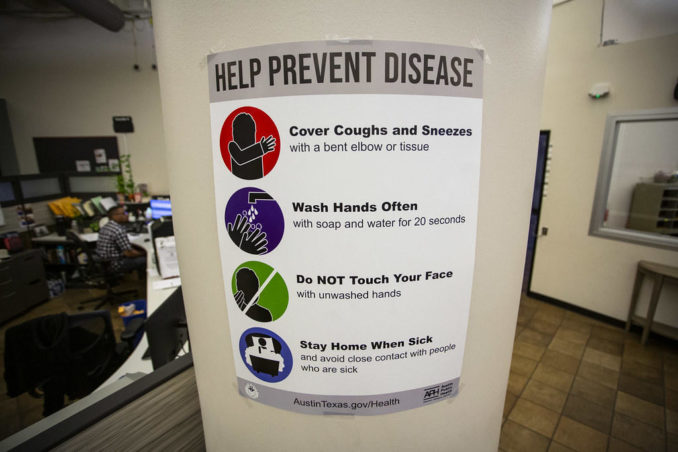

Sign in Austin, Texas

During this entire time, health care workers may or may not wear masks when in proximity to the patient. Triage tents are set up outside hospitals, but the workers are wearing no protection outside standard nitrile gloves, and there is no way to isolate patients while they wait to be seen.

Health care workers are already overworked thanks to the desire of our privately owned hospitals, nursing homes and ambulance services to maximize profits [during] COVID-19, and that is only making the issue worse. Rather than enough workers being brought in to take care of the influx of patients, we’re expected to work faster.

Health care workers — who include medical facility cleaners, cooks, record keepers and laundry workers — are not being tested, and the lack of guaranteed food, housing and income stability incentivizes us to hide symptoms. We’re largely left to do self-research on the virus. At my job as an EMT [emergency medical technician], the only training we’ve received on COVID-19 is a 20-minute video posted online that is not mandatory viewing.

We need more people on the job; we need a right to housing, food and health care; we need education on the virus; and most of all we need the profiteering to end.

A doctor’s scribe in rural Texas

The clinic experience here can be summed up in one word: inadequate. That’s thanks to a lack of organized response, research and education on COVID-19. There is little to no understanding from anyone at any level of care, from the clerks to the doctors, of the nature of this epidemic or how it is quantifiably or qualitatively different than influenza. They have consistently failed at every opportunity to give patients proper guidance and expectations for care of young children on through to elders.

It is likely that some folks here are already infected due to proximity to several large cities, and the incubation period is completely glossed over during triage of people at risk for infection. Symptoms can completely hide in young children, and they are not being kept away from at-risk populations. We can at best hope that we are late in the disease’s wave when we understand the stakes. The large population of retirees and the blasé attitude held by everyone except some few brave Cassandras means we are shaping up for a rough time. [Cassandra was the daughter of a Greek god endowed with the gift of prophecy but fated never to be believed.]

A former Central Texas nurse living in Germany

One of the first cases of community spread of COVID-19 outside of China occurred in Germany on Jan. 27. Yet there was not much known about the outbreak at that point, and people did not seem concerned. What struck me was that the person who transferred the virus had no symptoms when they interacted with others in the community who then later became ill. I have been surprised by the lack of a sense of urgency or willingness to take this coronavirus seriously, even today, as borders of major nations around the world begin to close and lockdowns take effect, and yet there are still so many flaws throughout the response.

People with symptoms are still not being tested because they haven’t traveled to China, yet the virus has been global since January. The hotline for people to call if they think they are infected in Berlin, Germany, where I live now, doesn’t have an option for any other language than German. This is one of the most ethnically diverse cities in Europe, and even in a crisis they require you to ask for help only in their mother tongue.

Another issue I see as a major problem early on was the lack of personal protective equipment supplies. I moved here from Central Texas in October 2019 where I worked as a registered nurse for nearly 20 years. My last job before leaving the U.S. was in surgery recovery. Similar to the emergency room, this is an environment that requires there be manual ventilation bags at each bedside. After Hurricane Maria devastated Puerto Rico [creating extreme need for medical supplies], we couldn’t replace these vital pieces of equipment, and many of them had expired.

There were also medications and other supplies we could not replenish, and it took months for manufacturers in the U.S. to ramp up production, while the U.S. government refused to invest in rebuilding Puerto Rico. I witnessed how quickly our operations could be compromised, even come to a grinding halt, without necessary equipment. This is exactly what is happening in Italy today, and I fear it is a sign of what is to come for the rest of the world that focuses more on maximizing profits rather than saving people’s lives.

A nurse working in Central Texas

I’m a registered nurse and I work in an inner-city psychiatric crisis center. More than half the patients we serve are homeless. The organization I work for is social-work driven and there are few RNs. I’m 75 years old and therefore a member of one of the vulnerable populations.

The organization’s leadership has been paralyzed by this whole thing. Last Thursday my supervisor, who has cancer and is on chemotherapy medications, was told she had to work from home. But she was not given a laptop, so she came back to work the next day. Then her supervisors told her to figure out how I could work without having direct patient contact. She came up with the idea that I could use her office and see the patients via telemed. I have been off work, but I’m due back at work tomorrow. My supervisor called me today to tell me the telemed idea fell through because leadership couldn’t find a laptop (again!) for me to use to plug into telemed.

I was given the option — and strongly encouraged — to stay home, but I don’t want to leave my co-workers short-staffed. As it stands now, my supervisor happens to be out with an upper respiratory infection (no, not corona!) so I’ll use her office and do everybody else’s charting, computer work and other stuff that doesn’t require patient contact. However inept their efforts, leadership does seem concerned about my safety. Either that or they know I’ve given my adult children instructions to sue.

At any rate, I don’t see that same level of concern for our clientele by my organizational leadership, by local politicians or by the federal government. Social distancing and good hand hygiene are the order of the day. How do you do that if you live in a crowded shelter and are on the streets all day?

A paramedic student in Austin

As an emergency medical technician and paramedic student I have witnessed firsthand the crumbling of our health care infrastructure in the wake of COVID-19. Clinical sites in hospitals across Central Texas minimized the initial spread of the virus and failed to implement increased protocols for infection control for weeks until it became all too clear the scope of this pandemic could no longer be avoided.

In a single six-hour clinical shift, every patient I came in contact with in the emergency room was a patient with pre-existing conditions, with signs and symptoms of pneumonia including cough and fever. These patients, exhibiting telltale signs of the virus, were all approached without an increased level of isolation within the hospital environment.

Within the last two weeks, the grant-based Emergency Medical Services system, in which I’m a clinical student, had only then begun conversations around ensuring that N95 masks properly fit providers. Staff also discussed concerns about a lack of masks and the inability to stock up on more as the wave of this pandemic slowly grew to a crescendo. Staff continually discussed issues with dispatch, but with a lack of continuity in terms of response to potential cases of the virus, some calls were being responded to with multiple units, others with single crews.

As of March 13, I was informed that my clinical education, as well as the entire medical professions department of my college, had been indefinitely put on hold due to the virus. As of now, I am unable to afford the state registration required to work as an EMT in the state of Texas and must take a back seat as I am unable to join my fellow health care professionals who continue to drown in a system that does little to put their well-being, let alone the patients’, at the forefront.

Only today, nearly a week into social distancing practices, am I hearing anecdotal reports of medical staff and patients receiving tests, as opposed to screening, for COVID-19.

Conclusion

COVID-19 is teaching many that we have no choice but to abandon profit-based medicine in favor of evidence and centralized planning. The reforms suggested by politicians such as Bernie Sanders are a start, but they fall short of what we need. The complete elimination of the profit motive and complete worker control over health care would allow us to focus on our most important task — patient health.

Health care workers who fall ill should feel able and supported to act in the interests of our patients and take time off, including extended self-quarantine should we become infected with COVID-19. We need testing that is readily available for everyone, especially those of us who care for the health of others.

The wealth we workers generate should go toward things that keep us happy and healthy, not an absurd Pentagon budget of $700 billion or another yacht for the capitalist vultures who prey on the sick and injured.