Reparations & Black Liberation

Workers World first published this article on June 6, 2002.

Lawsuits have been filed in New York and New Jersey targeting corporations that profited from the slave trade. These class-action lawsuits name three companies: Fleet Boston Financial, Aetna and CSX.

Fleet Boston grew out of a bank established by a merchant whose ships transported African slaves.

Aetna is an insurance company that encouraged slave owners to insure human property — not to protect their slaves, but to protect their investment in case of the slaves’ deaths.

CSX emerged from another company that used slave labor to build railroad lines.

The lawsuit estimates that the wealth in the United States created by the unpaid wages of slave labor is today worth $1.5 trillion.

Deadria Farmer-Paellman is the lead plaintiff and initiator of this suit. At a recent press conference, she stated, “My grandfather always talked about the 40 acres and a mule we were never given. These companies benefited from working, stealing and breeding our ancestors, and they should not be able to benefit from these horrendous acts.”

Political activist and attorney Roger Wareham filed this lawsuit on behalf of all African Americans. According to Wareham, the lawsuit is not about demanding monetary compensation for the descendants of African slaves in the U.S. Any money won from the lawsuit would go to a collective fund to help improve the housing, health care and education of African Americans.

Wareham, in an interview on the Black-oriented WABC-TV show “Like It Is,” told host Gil Noble, “Our strength is that the reparations lawsuit is part of a movement. The stronger the movement, the greater the possibility of the success of the suit. The most important thing is the success of the movement. The suit is just another part of that river of struggle that we are involved in.”

The December 12th Movement and the National Black United Front have called a “Millions for Reparations” national rally to take place in Washington, D.C., on Aug. 17, 2002 — the 115th anniversary of Black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey’s birth. The National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America is also building the demonstration.

Gov’t fears exposure of slavery’s legacy

The U.S. government has a despicable history of downplaying and outright dismissing the issue of reparations. To grant compensation to millions of descendants of African slaves would expose the institutionalized racism that African Americans and other people of color still suffer today.

The disproportionate number of African Americans populating U.S. prisons is just one glaring example of the legacy of slavery.

Back in 1989, Congressional Black Caucus member John Conyers from Michigan introduced bill HR 40, the “Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act.” Conyers said: “African slaves were not compensated for their labor. More unclear, however, is what the effects and remnants of this relationship have had on African Americans and our nation from the time of emancipation through today. I chose the number of the bill, 40, as a symbol of the 40 acres and a mule that the United States initially promised freed slaves.”

Conyers cited a number of objectives of the bill — including setting up a commission that “would then make recommendations to Congress on appropriate remedies to redress the harm inflicted on living African Americans.”

Malcolm X also raised the question of reparations in a speech on Nov. 23, 1964, in Paris. “If you are the son of a man who had a wealthy estate and you inherit your father’s estate,” he said, “you have to pay off the debts that your father incurred before he died. The only reason that the present generation of white Americans are in a position of economic strength . . . is because their fathers worked our fathers for over 400 years with no pay.”

The reparations struggle intensified with the military defeat of the Confederacy at the hands of the Union Army at the end of the Civil War. The victorious Northern government promised the newly freed slaves in the South “40 acres and a mule,” in effect acknowledging that brutal slave labor had not only greatly enriched the coffers of the former slave masters but also the emerging U.S. capitalist economy.

This just compensation for the freed people never came to fruition due to the counterrevolution that destroyed Reconstruction. In the “Compromise of 1877,” the Union Army abandoned the freed slaves, who had tried to bring about real social equality in the South by establishing their own institutions for political empowerment and elevation of their living and educational standards. For 10 years, the Union Army had played the role of a buffer between this progressive, democratic process and the former Confederate forces, who regrouped during Reconstruction.

The counterrevolution then evolved into a bloody terrorist campaign that drove the freed slaves to accept semi-slavery conditions. Under sharecropping, which still exists today, the former slaves went back to tilling the land of their former owners. They weren’t owned outright anymore, but had to work on the plantations for slave wages.

In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court legally sanctioned segregation as “separate but equal.”

Reparations struggle has taken many forms

Available in FREE download at workers/org/books.

In his 1903 masterpiece, “The Souls of Black Folks,” W.E.B. Du Bois wrote, “The problem of the 20th century is the color line.” Many Black activists and writers have looked to Du Bois’s words for inspiration in the continuing fight for Black liberation. Reparations became a very important focus in the Black struggle for the right to self-determination.

The Back to Africa mass movement in the 1920s and 1930s, led by the charismatic Marcus Garvey, was in its own way a demand for reparations. When the Black Panther Party created free breakfast programs and free access to clinics in the inner cities during the 1960s, this was another unique call for reparations. Affirmative action programs are also a form of reparations.

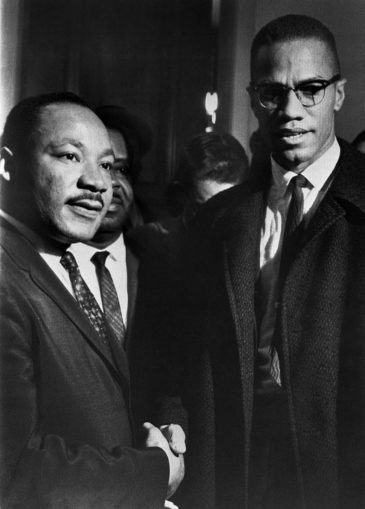

Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., leader of the traditional Civil Rights Movement, made a plea for reparations in his 1964 book, “Why We Can’t Wait.” He wrote, “No amount of gold could provide an adequate compensation for the exploitation and humiliation of the Negro in America (or the Caribbean or Brazil) down through the centuries. Not all the wealth of this affluent [U.S.] society could meet the bill. Yet a price can be placed upon unpaid wages. The ancient common law has always provided a remedy for the appropriation of one human being by another. The law should be made to apply for American (Caribbean and Brazilian) Negroes.

“The payment should be in the form of a massive program by the government of special, compensatory measures, which could be regarded as a settlement in accordance with the accepted practice of common law. Such measures would certainly be less expensive than any computation based on two centuries of unpaid wages and accumulated interest. I am proposing, therefore, that just as we granted a G.I. Bill of Rights to war veterans, [the U.S.] launch a broad-based and gigantic Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged, our veterans of the long siege of denial.”

The struggle for reparations received a tremendous boost at the World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa [in 2001]. The call for reparations, along with equating Zionism with racism, compelled the U.S. and Israeli governments to withdraw their high-level delegations from the conference. The Durban conference helped to provide worldwide exposure about the long-term, devastating impact of Western imperialism and colonialism on nationally oppressed people everywhere.

Marching through downtown Newark, June 24.