First published in the German daily newspaper Junge Welt on Dec. 16. Translation by John Catalinotto.

At the beginning of December, the Conference of Germany’s State Interior Ministers extended the ban on deportations to Syria without restrictions until at least June 2020. Originally, the interior ministers at their autumn meeting in Lübeck planned to relax the ban and allow deportations of serious criminals. During the conference, however, a gloomy picture of Syria was painted. The country “is anything but safe,” declared a church aid organization.

There were “hardly any education or training opportunities and few prospects of finding work and earning an income.” The health system was “at rock bottom;” there was not “enough intact housing.”

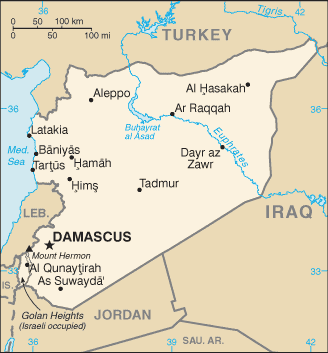

A Nov. 20 report by the Foreign Office addressed to the conference stated that there were “no safe areas for returnees.” It stated that attacks by “the regime” were possible anywhere and at any time, with the exception of areas currently under Turkish or Kurdish control or controlled by the U.S.

Contrary to what politicians and the media have described, however, the war has largely come to a standstill, except in Idlib and other areas in the north of the country. A different kind of war is now raging, however, due to the unilateral punitive economic measures of the European Union and an oil embargo by the U.S — an economic war.

Willing to return

Nevertheless, tens of thousands of people are still determined to return to Syria. They are coming from Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, and Syrians now living in Europe also plan to return to their homeland. A report by the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR) in October 2019 states that 75,501 refugees “spontaneously” returned between January and September of this year. It is likely this is a minimum estimate.

For 2019, an “increase in self-organized returns” is expected, although this presents a challenge, the report says. The UNHCR is trying to help by repairing shelters and providing legal assistance, subsistence and education. “The growing demands for support for returnees,” however, required more commitment from all the involved parties.

But the rich U.N. member states from Europe, the U.S. and the Gulf States are providing no support. The government in Damascus gets more and more isolated, and after all the war damage, now unilateral EU economic sanctions are destroying the Syrian economy. These sanctions were first imposed on Syria’s oil sector in 2011. Since then the sanctions have been repeatedly tightened and extended annually, most recently in May 2019 until June 1, 2020.

Currently, 269 people and 69 institutions and companies are on the sanctions list. They are subject to a ban upon entering the European Union, and their personal assets in European banks have been frozen. The pretext for the sanctions is that these entities are responsible for violence and repression against the civilian population in Syria and benefit from “support for the regime and/or being associated with persons or institutions of the regime.”

In addition to the entire Syrian government, military personnel, business people and their companies are on the list. These include Syrian Arab Airlines, the mobile phone provider Syriatel, the renowned daily newspaper Al-Watan, and all Syrian oil production companies and banks, including the Central Bank. Even the Syrian tobacco and cotton marketing organizations are subject to sanctions because they are state institutions.

Reconstruction made difficult

The unilateral punitive measures have a devastating effect, especially since they are linked to the U.S. oil embargo, which is also unilateral. In Aleppo, the businesspeople in the Chamber of Commerce and Industry are bound by the sanctions.

They “prevent us from building our companies and creating jobs,” said a businessman in Aleppo in an interview with Junge Welt. Instead, Europe is sending aid organizations to Syria: “They give us bread, but no work. People become dependent instead of living in dignity. Every worker we would hire would be able to feed [their] family [themselves].”

Only the U.N. Security Council has the authority to impose punitive measures on a country. Therefore, unilateral sanctions are contrary to international law. ldriss Jazairy, the U.N. Special Rapporteur in charge, has stated this legal concept time and again. The majority of the U.N. member states reject unilateral sanctions, but the rich Western states take the law into their own hands, he said, thus aggravating the danger of war internationally.

On Nov. 21 the Second Committee on Economic and Financial Affairs at the United Nations addressed the question of the legality of unilateral sanctions. Sixteen draft resolutions were submitted and two were adopted.

Among them was one calling on the “international community” to condemn unilateral economic, financial or trade sanctions because they prevent countries’ development. Punishments that are not authorized by U.N. bodies must be suspended. Such measures are incompatible with international law and contradict the basic principle of the multilateral economic system.

The resolution was approved by 116 U.N. member states, while two states — the U.S and Israel — voted against it. Fifty-two states, among them all EU states, including Germany, abstained.

Download the PDF May Day appeal to the working class Revolutionary change is urgent! Gaza…

Philadelphia On March 26, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court denied political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal permission to…

There are two important and overlapping holidays on April 22: Earth Day and Vladimir Lenin’s…

Twelve people were arrested April 9 for blocking traffic to Travis Air Force Base, a…

Secretary-General of Hezbollah Sheikh Naim Qassem delivered a speech on April 18, 2025. Resistance News…

Anakbayan Philadelphia held a rally on April 19 to demand the U.S. end its military…